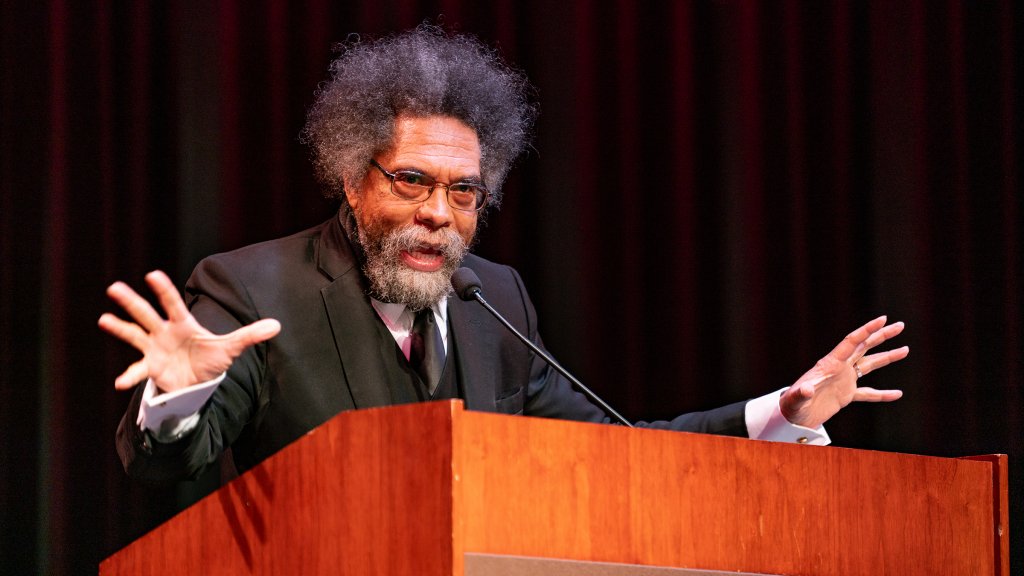

Dr. Cornel West knows how to make an entrance.

On Wednesday, May 11, Dr. West delivered the UC Regents’ Lecture in Schoenberg Hall at the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music. Dr. West’s decades-long status as a leading public intellectual – and philosopher, activist, musician, and actor – brought an enthusiastic crowd. To thunderous applause, West dropped to one knee, gave professor of global jazz studies Arturo O’Farrill a two-handed salutation, then joyously rose to embrace him.

Cornel West’s lecture, “The Musical Vocation in our Bleak Times,” was anything but dreary. West believes music is a vocation, not a profession, grounded in the spirit and speaking truth with honesty and integrity. He traced the subversive power of music back to the ancient Greek philosopher Plato and through the soul music of the legendary Curtis Mayfield. West’s concept of integrity stretched from 19th century transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson to author Henry James to human-rights activists Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr.

West was an inspirational presence to the UCLA students, faculty, staff and community members who were there.

“He really is a master storyteller. His dynamics, the way he changes his voice, his comedy,” said Seychelle Gabriel, a third-year ethnomusicology student. She recalled West’s stories about how African Americans faced down systematic terror with beauty rather than with violence. In the face of oppression, in the face of catastrophe, West emphasized, Black people in America had responded with courage, integrity, and with beauty. Music and beauty may not overcome the terror, but they exist in counterpoint with it.

West’s lecture covered the aesthetics of Black music in America, but he also stressed the universality of the musical vocation. All great artists, said West, struggle with the problem of what it means to be human. In so doing, they connect human beings together, and the present with the past.

“There is no vocation without invocation,” said West, urging musicians to invoke the great musicians who have come before them. Students pursuing the musical vocation should be in touch with their voices, said West, but also draw inspiration from musicians working in traditions the world over. He recalled how Edward Said, the great scholar of postcolonialism, found inspiration in Brahms’s piano concertos. Legendary crooner Frank Sinatra invoked the jazz vocal genius of Billie Holliday.

That idea of invocation is what initially drew Seychelle Gabriel to study ethnomusicology.

“My dad listened to a lot of classical rock music while I was growing up,” she said. “I found Jimi Hendrix, and then I found Muddy Waters, and then Bessie Smith, and you go back and back, and you find Storyville, New Orleans and all of the foundations. We all have a musical journey.”

West emphasized that artists pursuing the musical vocation must do so with integrity. This is all the more so in modern America, said West, where art is persistently judged in relation to its market appeal and where everything is for sale. Such pressures threaten integrity, and West admonished musicians to remain true to their roots and their own artistic selves.

“This is who we are, we are a continuation of the dead, of our grandparents,” said Mikey Aboutboul, a first-year musicology student from Israel. “Not just of our families, but people from the other side of the globe. This is what I love about musicology. When you learn about different music, you are learning about yourself. We are all part of the same humanity.”

Aboutboul paused for a moment. “This is what musicians really are. We are researchers of the soul.”

Cornel West’s talk went long. So did the questions, almost all of them from students. One student asked West about politics and protest in Palestine. Another student asked about race and integration, another about Afro-futurism, another about K-pop.

At one point, the moderator turned off the microphone in an apparent bid to wrap up the program, most likely out of respect for the speaker’s time. But West scanned the audience, one hand perched, salute-like, on his brow to block the glare from the stage lights.

“There’s another question over here,” he said, index finger extended towards the front row. “Young brother over here has a question.” The moderator dutifully switched the microphone back on and jogged over to hand it to the student.

It wouldn’t be the last question West would take.

Eventually, the talk and the questions did come to an end. The audience broke, some making for the exits and the drive home, others congregating in the hall, some in the open evening air on the steps to Schoenberg Hall. But well after most of the audience had departed, West lingered in the aisles, talking with students, taking pictures with them, and hugging each of them.

On his way out the door he spotted the one student he hadn’t yet spoken with, marched up to him and gave him a big hug. “Thank you for coming, my brother,” he said, waving one final time before leaving.

Cornel West makes a lasting impression, even when he is leaving the room.