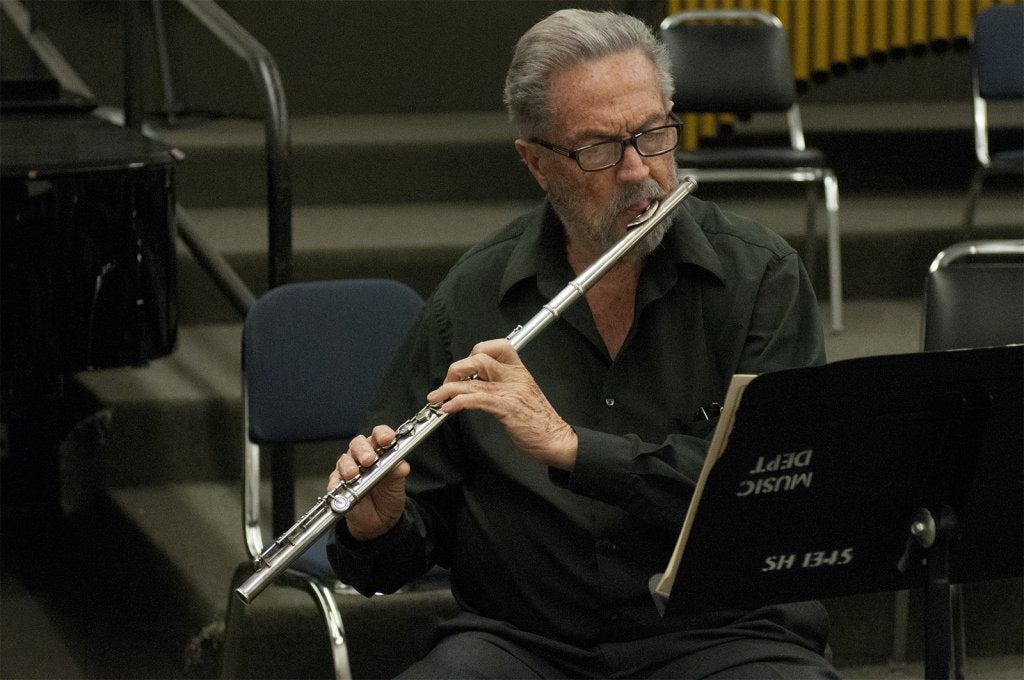

Flutist, UCLA instructor, composer and ubiquitous studio musician Sheridon Stokes passed away in July 2022. His career as a classical flutist and studio musician spanned over six decades. He was a beloved UCLA faculty member for nearly forty-five years and an anchor of the music performance wing of the music department before it became The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music.

“Sheridon’s career is inseparable from Los Angeles,” said Neal Stulberg, director of orchestral studies at The Herb Alpert School of Music. “He had a connection to its golden age that was lifelong.”

Sheridon’s studio career is the stuff of legend. He was the eerie, lurking presence in Jaws. He was the incantation of youthful hope in E.T. He was the heartrending penny whistle solo on the Titanic anthem “My Heart Will Go On” with Céline Dion.

“When I was growing up,” said Cheryl L. Keyes, professor of ethnomusicology at the School of Music and chair of African American Studies, “all of us young flutists wanted to show our hipness by playing the latest TV theme songs that featured flute, like Mission Impossible.” Keyes was imitating Sheridon, but she didn’t know it at the time. And if not Mission Impossible it could have been Lost in Space or Kung Fu or literally any one of thousands of television and film recordings over his long career.

Sheridon Stokes was in movies before he could sign contracts. As a member of the Robert Mitchell Boys Choir, he sang in The Bishop’s Wife in 1947 at the tender age of 12. He played piccolo with the Denver Symphony at 16, went on the road with Peruvian-American soprano Yma Sumac at 18 and landed a contract with Alfred Newman to play piccolo in the Twentieth Century Fox Orchestra at 20.

That last one made him the youngest contract musician in Hollywood history. His versatility and musicianship made him one of the most prolific.

“Sheridon told me that when he was first called to ask if he could play the Kung Fu series on wooden flute he immediately said, ‘Sure,’” recalled Jens Lindemann, professor of trumpet at the School of Music. “The fact is he had never touched a wooden flute in his entire life, and he learned it the night before going into the recording studio. We always used to laugh and say ‘That’s the most important lesson in music, just say yes to everything and be open.’”

“Sheridon was famous for being able to play whatever you threw at him,” said John Steinmetz, lecturer and bassoon instructor in the School of Music. “He was in baroque ensembles before the period instrument movement. He played classical chamber ensembles. He played new music. He was everywhere.”

Sheridon performed regularly at the Los Angeles Monday Evening Concerts. Stravinsky sat in the front row. Sheridon played in the Glendale Symphony. A young, unheralded composer heard him and sent him a note asking if he would play a new piece. Sheridon said yes, and the John Williams’ flute concerto was on its way to a premier.

Sheridon possessed a formidable cool. “He would play flute in the symphony with his legs crossed,” recalled Steinmetz. “Musicians used to say, ‘You know when the music gets hard, because Sheridon uncrosses his legs.’”

Once a guest conductor took umbrage at his relaxed demeanor and ranted at the symphony about how some people were being too casual and how this was disrespecting rehearsal, before storming off the stage. Sheridon leaned back to the bassoonist and said, “You know, I think he might have been talking about me.”

“Sheridon was beyond flute,” said Neal Stulberg. “And what he really loved, what he really thought of as his legacy, was his teaching. His students.”

“He and I once spent an entire lesson toying with how we could play the opening phrase of a sonata in as many different ways as we could imagine,” recalled Devan Jaquez, former student, and principal flute of the Knoxville Symphony. It was just such a holistic approach that set him apart.

He had high standards as a teacher, and his gruff countenance might have occasioned more than a little trepidation. But he inspired love and loyalty. “A few of us called him Sherbear,” admitted Jaquez. “His teaching continues to shape my art-making.”

“Lessons with Sheridon weren’t just about playing better, they were about being better, going with the flow, working hard and keeping an open mind because the world has so many surprises up its sleeve,” said Pénélope Turgeon, who graduated with an M.M. in flute performance in 2009 and is now principal flute of the Fox Valley Orchestra. “Thank you for the best lessons, Sheridon!”

“Sheridon had a wonderful energy about him, one of kindness, positivity, vitality, curiosity, and humor,” remembered concert flutist Anastasia Petanova, who earned her DMA from UCLA in 2019. “His ceaseless enthusiasm about the flute, music, and life was truly inspiring. I loved that one could ask him virtually anything, play him anything, and have great discussions about it afterwards. In addition to music, our lessons were often filled with laughs and personal stories. He was a wonderful man, teacher, mentor, and artist, and I feel very fortunate to have studied with him in his later years. I will miss him greatly.”

Colleagues at the School of Music recalled the same energy, the same dedication, the same joy. “There was always a twinkle in his searingly blue eyes,” said Neal Stulberg.

His colleagues and his students will always remember him. He played the soundtrack of our lives.

We invite you to celebrate Professor Stokes’ life, legacy, and artistry by supporting the Sheridon Stokes Flute Fund, providing scholarships and resources to students dedicated to studying flute performance at The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music.