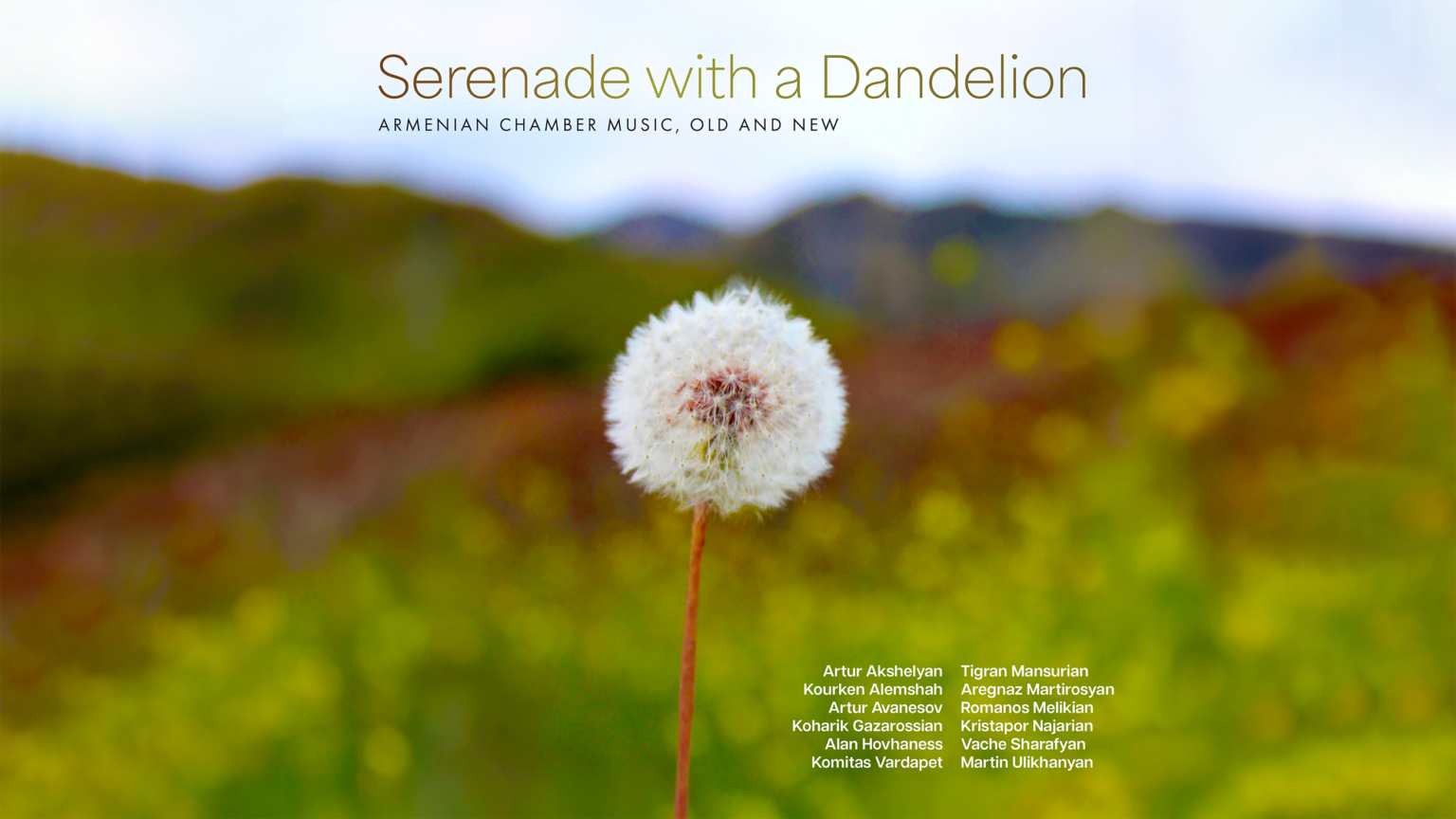

Serenade with a Dandelion

Monday March 4, 2024

7pm

Lani Hall

The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music

UCLA Armenian Music Program

Melissa Bilal, Director

The Promise Chair in Armenian Music, Arts, and Culture

Movses Pogossian, Founder and Advisor

Distinguished Professor of Music

Mary Sekayan, Coordinator

Performers

Coleman Itzkoff

See Bio

Hailed by Alex Ross in The New Yorker for his “flawless technique and keen musicality,” cellist Coleman Itzkoff enjoys a diverse career as a soloist, chamber musician, and educator. A prize winner at the 2019 Houston Symphony’s Ima Hogg Competition, Itzkoff made his professional debut at the age of 15 with Ohio’s Dayton Philharmonic and has since appeared as soloist with orchestras and in chamber music series countrywide. Recent season highlights include performances with the Houston Symphony, San Diego Symphony, Cincinnati Chamber Orchestra, San Jose Chamber Orchestra, American Youth Symphony at Walt Disney Concert Hall, Jupiter Symphony Chamber Players, Mason Home Concerts, The Philharmonic Society of Orange County, Caramoor, Texas’s Sarafim Music, and Virginia’s Moss Art Center. Future projects include recitals of baroque and early classical music, several commissions from composers, performing virtually for hospital patients in collaboration with Project: Music Heals Us, and continuing his studies as an Artist Diploma candidate at The Juilliard School. He has collaborated in chamber music with such musicians as violinists Pamela Frank, Shmuel Ashkenasi, Cho-Liang Lin, and Glenn Dicterow; soprano Lucy Shelton; cellists David Finckel and Johannes Moser; violist Roger Tapping; and pianists Gil Kalish and Peter Frankl.

Shoushik Barsoumian

See Bio

Armenian-American soprano Shoushik Barsoumian began her operatic career in Europe while under the tutelage of Mirella Freni in Modena. Over the next several years, she made house debuts in Italy, Romania, Malta and Austria, and Germany, singing notable roles such as Gilda at the Bucharest National Opera, Musetta at the St. Margarethen Opernfestspiel, Adina at the Teatru Manoel, and Oscar in the theaters of Como, Cremona, Brescia and Pavia. Her interest in the modern and contemporary classical music repertoire further led to performances of Stravinsky’s Svadebka, Ligeti’s Mysteries of the Macabre, Berio’s Sequenza III, and world premieres of composers Tigran Mansurian, Ian Krouse, and Arthur Aharonian, all performed with the Lark Musical Society in Los Angeles, California. Shoushik is featured in two releases by Naxos Records, namely as the soprano soloist in Ian Krouse’s Armenian Requiem, performed live at the Royce Hall in Los Angeles, and as La Fata Azzurra in Respighi’s La Bella Dormente nel Bosco, with the Teatro Lirico di Cagliari in Italy. A third CD release by Naxos Records is scheduled for March 2024, in which she and pianist Steven Vanhauwaert showcase songs from the Armenian Art Song repertoire. During the 2023-2024 season, Shoushik is scheduled to perform works of Bach, Handel, Mozart, Wolf-Ferrari, Menotti, and Bernstein with the Gerhart Hauptmann Theater in Görlitz, Germany.

Repertoire

Komitas Vardapet

(1869-1935)

Unabi, from Dances for solo piano

Qele Qele

Shoushiki, from Dances for solo piano

Steven Vanhauwaert, piano, Shoushik Barsoumian, voice (recording)

Koharik Gazarossian

(1907-1967)

Աղջի, Մէրդ Մեռել Ա / Ta Mère N’est Plus (1961)

VEM String Quartet: Movses Pogossian and Ally Cho, violins, Damon Zavala, viola, Niall Tarō Ferguson, cello

Tigran Mansurian

(b. 1939)

Allegro Barbaro (1964)

Antonio Lysy, cello, Mark Robson, piano

(performed at Dilijan Chamber Music Series on Jan. 12, 2014, Zipper Hall, Los Angeles)

Lachrymae (1999)

Jan Berry Baker, tenor saxophone; Varty Manouelian, violin

In Memoriam Antonio Lysy

Kristapor Najarian

(b. 1991)

A Tale for Two Violins (2014)

2. Kef / Festivities (Loy Loy)

5. Misty Morning / Lament

6. Escape

Kristapor Najarian and Movses Pogossian, violins

Artur Akshelyan

(b. 1984)

Sillage (2021)

2. Ablaze

Danielle Segen, mezzo-soprano; Movses Pogossian and Andrew McIntosh, violins; Che-Yen Chen, viola; Coleman Itzkoff, cello (recording)

Vache Sharafyan (b. 1966)

String Quartet No. 2 (2022)

Movses Pogossian and Andrew McIntosh, violins; Che-Yen Chen, viola; Coleman Itzkoff, cello

Artur Avanesov

(b. 1980)

Quand l’aubespine fleurit…

Movses Pogossian and Andrew McIntosh, violins; Che-Yen Chen, viola; Coleman Itzkoff, cello

Program Notes

Modulation Necklace: A Celebration of Armenian Music with Movses Pogossian

BY COLIN CLARKE (Fanfare Magazine)

This four-disc set of music by Armenian composers, Modulation Necklace, is a game-changer. Movses Pogossian is both an accomplished, prize-winning violinist and founding director of UCLA’s Armenian Music Program. Who better to birth this astonishing set, a release of remarkable breadth, replete with invention? The music is consistently presented at the very highest standard.

What was the inspiration for this set? How did the idea come about, and how difficult has it been to bring it to realization?

This set is, in fact, a natural continuation of the process started by the Modulation Necklace compact disc of Armenian music, which was released three years ago, also on the New Focus label. As a performer and organizer, I’ve been quite fortunate to be involved with performing and premiering a lot of Armenian music, both through founding and leading the UCLA Armenian Music Program, and also by directing the Dilijan Chamber Music Series in Los Angeles for 15 seasons. I am also very lucky that some of my best friends happened to be amazing composers! Regarding the difficulty: Of course, it’s been hundreds and hundreds of hours of creative, organizational, and administrative activity, not without stress—but well worth it.

What are you hoping to archive in the release of this set? A new appreciation of Armenian music for listeners?

Absolutely! There is so much to archive and to celebrate. I was kind of astonished with how this project mushroomed to four discs and 270 minutes of music, and it could have easily been a double of that. By including a wide range of composers, from the revered Komitas Vardapet to the pieces written as recently as a year ago, the aim was to point the listeners to the vast richness and beauty of the Armenian musical culture, old and new. We already have plans for the next instalment in our Modulation Necklace series; we just need to catch some breath first.

Regarding the dandelion-inspired piece, the derivation of the name (“Dent de lion,” lion’s tooth) perhaps reminds us that there is a nobler aspect to this humble plant that is normally construed as a weed. Certainly, Armenian composer Vache Sharafyan seems to realize this in his lovely and quite complex Serenade with a Dandelion for two violins. Heard in a lovely performance here, it’s highly atmospheric. I also like how the use of stopping gives the impression of more than two instruments, too. How would you introduce this piece? And as one of the two players (with Varty Manouelian), what challenges does Sharafyan’s score pose to the performers?

Vache’s colorful, imaginative music has the built-in effect of taking the listener on fantastical journeys, and is almost therapeutic in nature. Serenade with a Dandelion has a special place in my heart. It is a gift from Vache to my wife Varty and me, with which we opened the very first concert of the Dilijan Chamber Music Series, back in 2005. The composer eloquently describes the piece in his program note: “... softness and lightness, freedom of the imaginary flight, transparency of the dandelion seemed very close to the kernel of the musical idea in the Serenade. Meanwhile, the dandelion consists of a confident lion as well: strongly in love, even somehow drunk out of love, and so rich of imagination.…” I could not have said it better—and, frankly, it’s been a labor of love, both in premiering the piece two decades ago, and in bringing it back for this recording.

There can’t be many pieces for solo saxophone and viola, but Tigran Mansurian’s Lachrymae suggests maybe there should be more! What a powerful piece this is, written in 1999 when a close member of Mansurian’s family was ill. This blew me away, with its two intertwining lines, independent and yet related (on a very immediate level, the timbres are not too far distanced from each other). Am I right in thinking that drooping phrases indicate the sense of loss? (Interestingly, I reviewed Sharafyan’s Petrified Dance in Fanfare 46:1, which is a dance of mourning, linking the two composers—Gems from Armenia on BIS, Fanfare 35:4.) In his review of Mansurian’s “Bagatelles,” James H. North speaks of leaning on the composer’s heritage (Armenian) but within a modernist perspective. Would you say that’s fair in relation to Mansurian’s music?

I think it is, overall, a good description, but I would add a good number of layers and angles to this modern classic of Armenian music. Tigran Mansurian’s impact on the generations of Armenian composers is matched, in my opinion, only by Komitas and Khachaturian. Always evolving, his more “modernist” pieces of the 1960s to the 1980s closely aligned themselves with the revolutionary and defiant spirit of Schnittke, Silvestrov, Pärt, and Denisov—all of them being his close friends. Gradually, Mansurian’s music has entered the realm of transparency and deep homage to the modal universe of the Armenian musical tradition. I think this set gives listeners a good representation of Mansurian’s inner world, as the three recorded works are really different from each other.

Sharafyan’s Second String Quartet is remarkable. Cast in what the composer calls “chain” form, in which each section births the next, it’s an incredibly varied experience expressively. Occasionally I hear Janáček in the repetitions of cells, but then it veers off in a totally individual way. Some of the writing is incredible—long, fast passages followed by almost playful modernist moments in which discontinuous phrases on each instrument create an impression of misaligned clockwork. Again, you’re performing here (first violin) with obviously esteemed colleagues. How did you go about interpreting this piece? What would you say makes it individual?

I’ve known Vache for more than 30 years, and, frankly, lost track of the amount of works that I was fortunate to be involved with, as either a commissioner, a first performer, or simply as a friend. His output is truly enormous. However, I agree with you that the Quartet No. 2 is indeed something else. I recall how we were reading it for the first time with my wonderful collaborators Andrew McIntosh (himself an amazing composer, by the way), Che-Yen Chen, and Coleman Itzkoff, literally marvelling at the twists and turns of this remarkable scenic drive-like experience, with happy smiles on our faces. While the piece has considerable technical difficulties, once they are conquered, it sort of plays itself—we are just letting ourselves be taken for a ride in a fairy tale.

The name Akshelyan (Sillage) is new to me—and it turns out to be new to Fanfare too. Could you introduce the composer, perhaps, and how this piece came to be included?

Akshelyan is one of the most prominent representatives of the post-Soviet generation of young Armenian composers, and I am delighted with the result of our first collaboration. I was approached by Alec Ekmekji, an aficionado of Armenian music and UCLA’s VEM Ensemble (which at that time consisted of mezzo-soprano Danielle Segen and a string quartet) about ideas for a commission. Alec happened to be good friends with the poet Zareh Melkonian’s daughter Lina, who was very kind to work with the composer on choosing the texts that appealed to him. The result is Akshelyan’s Sillage, which, in my opinion, is a marvelous piece: haunting, complex, and full of fantasy and colors. To quote Akshelyan from his program notes, he was “rather on the philosophical side of it, as if the different time fragments of life and death coexist in our memory, and we are impacted both from past and future events. Therefore, musically speaking, I had to include short phrases or sometimes repeated words.… I considered quasi-soft and meditative passages along with abrupt and ad libitum interventions, in which the repetition of words will provide a dynamic link between voice and strings, and the ‘nature of the moment or instance’ will project the ‘emotional sillage.’”

There’s something of the viola in Berio’s Folk Songs here (I’m thinking of “Black is the Color of my True Love’s Hair”). Firstly, could you introduce the poet upon which this is based, Zareh Melkonian?

I did not know about the poet until this project. Here is a beautiful write up about him by Lina Melkonian, his daughter—I hope it’s helpful!

The three movements are centered around a poem called IT. The music plays with traditional modes of writing (to represent the past) as well as more modernist techniques. The finale almost sounds like a folkish lullaby to me. The performers are remarkable—the control of all of them, but particularly the singer, is stunning. How did the choice of performers come about?

The piece was written specifically with the voice of Danielle Segen in mind (see above about that). The composer and Danielle were in communication about the vocal range, preferences, and so on—and it really paid off. Regarding the string quartet, I plead guilty to hand-picking musicians that I admire and love playing chamber music with. A few years back, Andrew, Che-Yen, Coleman, and I collaborated on a Kurtág “Hommage” program, which stands in my memory as one of the most satisfying immersive and spiritual experiences that I have ever had as a musician. The Avanesov miniatures were premiered at that concert, and naturally I wanted to bring back the same cast—and I am lucky and grateful that it was possible.

The scoring of Chameleon by Aregnaz Martirosyan takes us back to strings and sax—this time a solo violin with alto sax. The impression is generally light, until those sudden punctuating syncopations. Interestingly, it uses a Komitas folk melody as part of its material. That speaks of a sense of national pride as well as high imagination. How important is that sense of national identity to Armenian composers in general and Martirosyan in particular?

I am glad you picked up on that. It’s fair to say that a reverential relationship to Komitas is quite characteristic for the Armenian composers of the new generation as they steadily move away from the dogmas of the dated Soviet Realism and embrace the depths of Armenian music’s ancient identity.

It’s time to move on to Disc 2: Armenian Art Songs. Who is Vatsche Barsoumian, who is mentioned in the notes?

My dear friend and a musician of rare insight, Vatsche Barsoumian has built an oasis of Armenian culture in Glendale, CA by founding the Lark Musical Society 30 years ago, as well as its offspring, the Dilijan Chamber Music Series, which he asked me to lead in 2005, for what became 15 memorable seasons, packed with commissions, premieres, and highly committed chamber music-making. Vatsche is one of the world’s foremost scholars on Komitas and Armenian music in general, and has been instrumental in dreaming up the concept of an entire compact disc dedicated to Armenian art songs, which are performed beautifully by Shoushik Barsoumian and Steven Vanhauwaert.

The first eight songs are by the composer usually just known as Komitas, although his full name is Komitas Vardapet. Can you introduce him a little and discuss what makes his music so special? Can you perhaps also speak about the importance his work has had on other Armenian composers who followed him?

This is a question that would require an entire book to be answered properly. A truly watershed figure in the history of Armenian culture, Komitas Vardapet has been rightly called the “savior of Armenian music.” He was a priest and a victim of the Armenian genocide of 1915, during which he fell victim to the purge against Armenian intellectuals. As one of the eight survivors from the prison camp he was deported to, he suffered from deteriorating mental health, and was eventually transferred to a clinic in a suburb of Paris, where he spent the rest of his life, dying in 1935. As an ethnomusicologist, very much like Kodály and Bartók for Hungarian music, Komitas collected and documented thousands of Armenian folk songs. As a scholar, Komitas wrote in-depth treatises about the unique Armenian modes, as well as doing invaluable work deciphering the unique notational system called “khaz.” As a composer, while his input is limited (mostly for, choir, solo piano, and voice/piano), he left us with gems that are venerated in Armenia, and are finally receiving international attention, thanks to ECM recordings and performances and also recordings by some very prominent musicians such as Kirill Gerstein (who is soon releasing a highly anticipated Platoon recording that pairs Komitas and Debussy) and Grigory Sokolov. It is a known fact that after one of the triumphant performances of Komitas’s choir in Paris, Claude Debussy came backstage and knelt in a gesture of admiration, saying: “You are a genius, Holy Father.”

I’m intrigued by the sparse nature of the scoring—often a piano single line and voice. It’s as if he achieves maximal effect through minimal means. Is that a fair appraisal?

Just like you, I find that particularly impactful!

... but the melodies themselves are highly ornate—are the decorations part of the Armenian musical vernacular? And, I love the singer, to be honest—a lovely voice, clear and yet warm. Her diction seems excellent as far as I can tell (in the sense that syllables are clearly defined—I don’t speak Armenian, I’m afraid!).

I fondly remember 18-year-old Shoushik at the very beginning of her career, still a student at USC, mesmerizing the audience by singing Komitas with such purity and nobility that it took my breath away. A beautiful person and musician, she has so much to offer with her innately deep interpretations, which stay away from external effects and aim to concentrate solely on the meanings of the texts and the music. I love this kind of ego-free musicianship so much.

There seem to be extremes of emotion here. The fourth song is ultra-beautiful; “Homeless,” the sixth song, is unbearably sad. The last two Komitas songs are both centered on the crane (the bird, not the mechanical object!). Is this a meaningful symbol in Armenia?

Cranes have a special significance for Armenians, related to our tragic history full of trauma, ethnic cleansing, and migration. Many folk songs and poems are dedicated to cranes as symbols of homesickness.

Romanos Melikian (1883–1935) is a new name to me—would you care to introduce him to Fanfare’s readers? There are only two songs by Melikian here—but there’s a lot of beauty in the filigree delicacy of Glowing in the Garden and the incredible pain of Weep Not. Is there much more to discover? I hope so! I wonder why we don’t know more about Melikian—only one of his pieces, Emerald Songs, has been reviewed in Fanfare before.

Well, this is one of the reasons why this CD set is conceived: also to bring attention to some wonderful Armenian composers of the past who are not much known yet outside of Armenia. The widely educated musician, composer, and choir conductor Romanos Melikian, a Moscow Conservatory graduate, is the founder of the first National Conservatory in Armenia’s capital, Yerevan, in 1921. (I am a proud alumnus of the Conservatory, and therefore one of the many beneficiaries of Melikian’s vision.) Due to poor health and a busy life as an organizer, Melikian’s compositional output is not large, but it is exquisite, and consists of mostly works for voice. Interestingly, the pianist in the recording to which you refer, Emerald Songs, is Artur Avanesov, who is featured prominently in our project, both as a composer and performer.

There are no previous pieces by Kourken Alemshah (1907–47) at all in the Fanfare Archive. And yet his I Loved seems like a cross between a Schubert song/melodrama and Eastern harmonies and melodic constructs. It is quite remarkable (and, I have to say, the singer is astonishing in her high register in “Wish”). What would you say makes Alemshah’s writing unique?

Yes, Alemshah was another important figure in Armenian music who is finally receiving some well-deserved exposure. Unlike Melikian, who received his education in Moscow and worked on the fringes of the Russian Empire (and later Soviet Union), in Yerevan and Tbilisi, Alemshah was a member of Turkey’s Armenian minority, and was later educated in Milan. He settled in Paris in 1930, and that’s where most of his creative activities occurred. In addition to composing, he also founded the “Cilicia” choir, which became a well-known choir in the Armenian community of France. In 1933, at the age of 26, Alemshah was invited to join the Association of Musical Authors, Composers, and Editors of France (SACEM). In 1937 his work Armenian Wedding, a combination of Alemshah’s music with popular songs, won the second prize at the international competition of People’s Music, with the participation of 20 nations. In the 1930s, he composed under the pseudonym of Jean Valdonne. In 1939, Alemshah was appointed to direct the Sipan Komitas choir, which he led until his death. He conducted Armen Tigranian’s opera Anoush and the performances of the Armenian Divine Liturgy in a number of French cathedrals. I’d say that Alemshah’s music is infused with his upbringing and deep love of Armenian music, but also highly influenced by the European training that he received, and the cosmopolitan environment of Paris, which at that time was a mecca for artists.

Finally for this disc, there are six songs from Tigran Mansurian’s Songs from Canti Paralleli. You refer to this in the notes as the best representation of the genre of Armenian art song. And I also see what the singer means in her booklet notes about the hypnotic nature of the piano part (which she says influences her deeply, and it certainly comes across as such in the music). Also, the song “Over the Blue Lake” in particular seems to exemplify this. Why is the set called Canti Paralleli?

The title of the cycle refers to the fact that the composer used two poems each from three different Armenian poets (Paghtasar Dpir, Yeghishe Charents, and Avetik Isahakian). Actually, the enhanced version of the cycle has two more poems added by Vahan Teryan, but the recorded version has a total of six songs. They are indeed pure gems, perfectly balancing poetry and music, with such a degree of piercing transparency that it takes your breath away from the very first note. As I mentioned earlier, Tigran Mansurian’s uncanny connection to the Armenian language and literature is unique, and his late compositional style suits those poignant texts like a glove. It is actually Vatsche Barsoumian’s opinion that Canti Paralleli is the best representation of the Armenian art song, and I fully agree with him. What makes it special is that Shoushik Barsoumian had several opportunities to work with the composer on these songs, in preparation for the 2012 premiere performance in Yerevan, Armenia, so I think we have a definitive version of this masterpiece documented for posterity.

What about the poets that these composers set? It’s difficult in translation to catch the subtleties of their verse, of course. What are their specific characteristics as poets, and how do you feel the composers translated (or worked with) that in their music? Also, is there an Armenian school of poetry, and if so what are its characteristics?

The poems set to music by the composers in this collection are very diverse and represent different historical periods of Armenian poetry. Finding common themes among them is truly impossible because they cover a time span ranging between troubadour poetry and Futurism. In addition, due to the distinct difference between the Western and Eastern Armenian languages, two schools of Armenian poetry can be identified. While having different phonetics and orthography, Western and Eastern Armenian are two mutually intelligible branches of the same language. Due to political and historical circumstances, the two schools often differ not only linguistically but also stylistically. The musical settings of these poems rather reveal their intrinsic qualities (through the prism of the composers’ individual styles) than tend to find a common theme between them.

Moving to the third disc, Artur Avanesov has at least made it into the Fanfare Archive with his Feux follets, which I reviewed back in 43:5 (with yourself as soloist, on the New Focus disc Modulation Necklace). His Wondrous It Is... is based on a melody by the eighth-century poet Khosrovidukht and is poignantly scored for string trio. It’s absolutely lovely—what was the intent of the original melody? Is a “sharakan” a particular type of church melody?

Wondrous It Is… is Avanesov’s arrangement of the sharakan (church hymn) by the eighth-century Armenianauthor Khosrovidukht Goghtnatsi, one of the first known female music authors in the world. Khosrovidukht’s song is dedicated to the memory of her brother Vahan, who was abducted by Arabs, forcibly converted to Islam, and spent twenty years in a prison. Upon his release and return to Armenia, Vahan converted back to Christianity but soon met a violent death as a martyr.

It is incredible to think that this string trio piece was written in 2023, so many years after the original, and yet it seems to maintain the original’s sense of holiness and devotional respect.

I agree wholeheartedly! It draws you in instantly, and holds you in its spell until the very last note, a delightful pianissimo grace note by a lone violin that is an homage to Armenian folk tradition.

It’s a terrific performance, too—there’s so much control from the players. I do wonder how much rehearsal and recording time they had, as the standards are so high throughout the set!

This is really a labor of love. I am so incredibly proud of the young performers, members of the VEM Quartet (two graduate students and a recent alumnus). The piece was commissioned by the UCLA Armenian Music Program, to headline a concert tour of Armenia in the spring of 2023. In a short period of time, from early March through mid-May, Ela, Damon, and Niall have performed it on multiple occasions, from outreach events for school children in Armenian provinces to high-profile concerts in Yerevan and Los Angeles—always to an incredibly receptive reaction. They also got to work on it with the composer (who took part in our tour as a performer as well). By the time they recorded it in late May 2023, they really owned it.

It is nice that this is followed by Avanesov’s String Quartet No. 2; but the title of the first movement shocked me before I even heard a note—“Cognitive Study of the Generative Anxiety Disorder.”

Artur sometimes shocks me with his titles. But I have to say, it is an accurate and, actually, helpful insight into the piece for us, the performers!

The quartet took him four years to write (2019–23) and yet remains a work in progress, with more music to add. We have four movements so far (rather neatly, that does fit with the general conception of a string quartet!) Three of the four movements are linked to Feux follets, right? (That’s another piece that is in continuous evolution—some 70 pieces so far! Or more by now?)

As Artur Avanesov writes in his program note: “... this is another work in progress that will eventually comprise many small units. These could be deliberately selected and played in any order. So, the title String Quartet does not refer to any specific musical form; instead, it is just a description of the instrumental combination for which the composition is written. The present recording features all four pieces existing at this moment. Three of them are linked to the corresponding Feux follets pieces.”

What are the challenges for the performers of this music?

We worked a lot on these pieces. They are deceptively short but rather complex and tricky to put together. Performers are asked to combine a Berg- or Webern-like precision of coordination (lots of complicated twists and turns, counting can be tricky, etc.) along with a very Romantic and “in the moment” aesthetic of freedom and improvisation. So, you have to be very focused and aware, but also comfortable enough to play rubato. It is very rewarding, though!

So, on to the “Generative Anxiety Disorder.” My own impressions are that a motif, heard at the opening, returns again and again, as if in escalating Angst. The Angst seems more harmonically generated in the second movement, “Drammatico.” Here, folklore meets microtonality in the most astonishing compositional dance. And I love the song of the third movement. Hushed and as intense as the slow movement of a late Beethoven string quartet, this is remarkable (although shorter than I expected from the gravity of the materials!) A medieval French folk song forms the inspiration for this movement here, “Quand l’aubespine fleuret” (When the Hawthorn Flowers)—truly beautiful.

I’m going to skip over to the fourth disc at this point, as it contains pieces by Avanesov related to the above—a sequence of nine pieces from Feux Follets. They are fascinating—the way he embraces Schubert and internalizes Des Fischers Liebesglück is remarkable. Various other songs are referenced (there’s no missing Der Tod und das Mädchen!). It’s very clever but remarkably affecting at the same time, as Schubert morphs into a more Eastern version of himself and then into Avanesov himself. This internalization of other composers seems very personal to Avanesov, doesn’t it?

Definitely. Everything is personal for Artur, and for someone with his encyclopedic knowledge of music it seems only natural that he is “besieged” by references and reverences, so to speak. Actually, the great György Kurtág, whom I have the great honor of calling a mentor, functions in a similar manner as a creator. Of course they are very different, but I do see this common trend between them.

Just as clever is La lumineuse, a take on the character pieces of the French clavecinists of the era of Louis XIV and Louis XV! It has clear traits derived from them, yet still maintains something of Avanesov’s identity. I find these pieces very playful—and very, very clever. Avanesov’s Grieg piece again leaves us in no doubt as to the references; nor does the late Brahms (Intermezzo II). The booklet notes on the latter make an interesting point—the Intermezzo is no longer between two pieces but between existence and non-existence. Would you care to expand on that?

That is vintage Artur: He takes something very common and traditional, and looks at it from a unique angle. As he eloquently explains in his program note, he is looking for the “... moment of meditative suspense between existence and non-existence, a moment of absence from both life and death, or that of presence in both at the same time.”

I never expected to see Alban Berg as one of the composers, much less one of the Altenberg-Lieder as a dropping-off point, but here it is in “Hier ist Friede.” The melodic similarity is crystal clear, as are the harmonic references. Would you agree there is an expressive similarity between Berg and Avanesov?

This is very perceptive of you to notice; I agree fully.

I think I find “Für Hanni,” an in memoriam piece, the most touching—this became a choral piece, I believe? And the idea behind it is very effective—an ascending, “winding stair-like” ascent amongst the Minimalist gestures. I also imagine this takes quite some control from the pianist.

Artur is truly a great pianist; I sometimes call him the “Armenian Thomas Adès,” because both of them have mesmerizing pianistic abilities in addition to being great composers.

It’s fascinating, too, how the composer creates a prolongation of this in the next movement, “Nenia” (a dirge)—and, taking the title as another catalyst, references exist to Brahms and Kurtág in the music.

It’s also interesting how, in the two Intermezzos here, the composer refers less to Brahms (certainly in the final one) than to the end-of-century likes of Mahler—and Kreisler and Joseph Marx are also cited. I don’t know enough about Marx’s music (although I know the odd piece) to comment—how does this link to it? This final Intermezzo is very elusive indeed, almost fragmentary. Am I right in hearing some Armenian tropes in there, in the sudden flurries of notes and some of the melodic shapes?

I was so curious about your take that I relistened just now, and am actually hearing an homage to Rachmaninov (and Brahms and Mahler, of course). But we’d have to ask Artur!

I’m surprised (again!) by the inclusion of the music of Ethiopia in Tezeta—and surprised this piece seems to move towards modern jazz improvisation at times! I’m lucky enough to be able to read the notes for this release, but could you perhaps explain to the readers the relationships between Armenian and Ethiopian indigenous musics?

There is indeed an unbelievable connection between Armenian and Ethiopian musical cultures and histories, something that I learned myself relatively recently— thanks to the significant and important research by Paris-based composer Michel Petrossian (whose brilliant Piano Trio is on our first Modulation Necklace album). To quote Avanesov from his notes: “... while visiting Jerusalem in 1920s, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie I came across Armenian orphans who survived the Armenian Genocide of 1915. Having learned their story, he felt so compassionate that he took forty orphans to Addis Ababa, where he entrusted them to the care of the Armenian musician Kevork Nalbandian, author of the Imperial Anthem of Ethiopia. The Arba Lijoch (“forty orphans”) formed the imperial brass band of Ethiopia; many of them permanently settled in the country, thus influencing its musical life.”

How crazy is that? Basically, by a random act of historical coincidence, a single Armenian musician, Kevork Nalbandian, writes a National Anthem of Ethiopia, and is rightfully credited with establishing the professional musical culture of an entire country!

Also regarding Tezeta: I’m intrigued by the following: “Though written for piano solo, the piece was conceived as an imaginary conversation between several saxophones, keyboard, and drums.” That seems oddly specific; it is again performed by the composer, so one assumes he had this in his mind during the performance. Occasionally, I confess, I thought of steel bands in this piece! And yet it is deeply serious, not flippant at all. To me, it feels like a tone poem for piano.

It is truly a unique soundscape. Imagine hearing it on Avanesov’s upright piano in his apartment in Yerevan, Armenia, when he first played it for me upon completion in the late evening. He is lucky to have very kind neighbors who adore him!

You also have the honor of having first recordings by the composer himself! Small wonder they are so convincing, musically!

That goes without saying.

Avanesov’s Tre Sonate (Three Sonatas) that closes the entire set seems immediately more approachable, even open-air. It pays homage to the form of the piano trio, and exudes a real affection. There’s a rather nice formal touch here: Each sonata can be played separately, but when played together they form a very satisfying three movements (fast-slow-fast). The first is great fun, a tribute to Scarlatti. (I love the rapid violin descent rounded off by a low staccato piano note at an octave displacement—put together, a typical Scarlatti left-hand gesture.)

And from Scarlatti one moves to Bach (the St. John Passion, and even more specifically “Zerfließe, mein Herze,” heard right near the end of the piece). There’s no missing the link between the two if you play them one after the other—and the vocal original certainly seems to encourage a sense of cantabile from the players, especially cellist Edvard Pogossian (who carries the melody for the majority of the time, only briefly ceding it to the violin of Varty Manouelian). It’s truly lovely, and appears to me as a real tribute to old JSB in the most tasteful manner possible. Does Bach hold a particular place in the hearts of Armenian musicians?

Well, I think Bach holds a particular place in the heart of every musician, and Armenian musicians are not an exception.

The final movement—the notes refer to a two-reprise form, by which I take it you mean both sections are repeated. There’s a lot of clever aspects to this movement mathematically—would you care to explain them to our readers? And how it does works musically! (To me it’s like a game, and we hear that playfulness in the music itself, but maybe that’s just me! There is some drama there, but I wonder whether it is tongue-in-cheek melodrama.)

Yes, this movement is a rather witty play on various numbers (four and three), and also cleverly goes through an entire chain of chromatically descending modulations from C Major back to C Major, thus covering all 12 (four times three) tonal centers. This is done while keeping a strict structure of 27 (three squared) measures per cadence, throughout an entire movement!

We have a first recording of Mansurian here in the piece Tremors, right? This is a string quintet, as opposed to a quartet. It occupies a special part in Mansurian’s output for its transitional nature—a departure from his fascination with the European avant-garde and a move towards nationalism, perhaps? It also seems particularly gritty at some points, against which the elegiac passages seem even more peaceful. It’s a terrific piece, and I almost feel that calling it “transitional” does it a disservice, as it works perfectly well in its own right. What do you think? What makes this piece so special to you? And how was the process of discovering the score for you and your colleagues as you worked on it? Certainly the performance implies deep work as you reveal the piece’s structure so well, and the climaxes therefore carry real weight.

I believe Tremors is the last major chamber work by Mansurian that has not been recorded yet, and sort of completes the circle of documenting his impressive body of work for posterity. Stylistically, it closely aligns with composer’s String Quartet No. 3—another dark, edgy, at times thorny-sounding masterpiece. I particularly love how the piece ends, with a ray of hope (the violin in a very high register), and then an unanswered question by a solo viola (the composer’s favorite instrument). Actually, I am not performing in this piece; instead it’s my young student colleagues from another VEM incarnation, joined by my distinguished former UCLA colleague and friend, cellist Antonio Lysy, who sadly just passed away. I had the pleasure of being in the booth and producing this wonderful performance.

I’m absolutely intrigued concerning the title and basis of Martin Ulikhanyan’s Fantasy on Tigran Mansurian’s Film Music for clarinet and string quartet. Film music tends to be considered as something less than concert music in the West, and yet this works beautifully. The composer says he’s “personally very close to the composer.” What does he mean by that?

To start with, Armenia is a relatively small country, and when it comes to the cultural circles, everyone pretty much knows everyone! As for Tigran Mansurian, literally every Armenian knows his name, and can sing the beautiful bittersweet melody from the film A Piece of Sky, to which Mansurian wrote the music. Martin Ulikhanyan is one of Armenia’s most recognized composers in the genre of film music, and so my idea was to commission a piece from him that would pay an homage to Mansurian’s most beloved tunes from various films, while remaining an original composition. I think Martin has done it splendidly.

The piece is lovingly crafted, and just as lovingly played! The pizzicato section is particularly fetching. I think there are some passages I could identify as “filmic,” but that is by no means the rule, and Ulikhanyan seems to use that as part of a strategy of contrasts.

It’s also great to see some Hovhaness here, surely the most famous of the composers in this set. He qualifies as an “American composer of Armenian and Scottish descent”! What I find remarkable is that he has a completely individual musical signature.

I confess that when I was younger and cockier, I tended to look down on Hovhaness as a second-rate composer. Thankfully, I have matured somewhat, and now admire not only his remarkable output (over 400 works!), but also his holistic worldview as well as his reverence for nature. I think that in his chamber music especially, Hovhaness is like a chameleon, constantly reinventing himself. He is also never in a hurry, a quality I wish I had! I find it interesting and telling that he was friends with the great American composer Lou Harrison. Having had the pleasure of performing several times at Lou Harrison’s magical house in Joshua Tree (which has the best acoustic in the world, by the way, designed by Lou himself), it was very touching to see the correspondence between the two great men. When we worked on the String Trio with the VEM, we tried to make sure that the idiosyncrasies and non-conventional sections of the score are brought out and celebrated rather than undermined—and I am really happy with the final result.

The Gazarossian Lament is very powerful; and while I admire the recording of her Etudes on Piano Classics (46:6), I find this far more profound. But few will know anything about Koharik Gazarossian (1907–67). Again, would you care to introduce this composer?

I am so glad you enjoyed discovering this piece as a listener! Hailing from the genocide-surviving Armenian minority of Istanbul, Koharik Gazarossian was an active member of a circle of Armenian feminist intellectuals, writers, and artists, and one of the first women composers of the Republic of Turkey. Graduating the Paris Conservatory, she toured Europe, the USA, Lebanon, and Egypt, performing as a concert pianist in major concert venues, including Carnegie Hall, the Salle Gaveux, and Wigmore Hall. Written in Paris in 1961, Aghchi Mert Merel A / Ta Mère N’est Plus for string quartet takes its theme from a melody transcribed by Komitas in 1913 during a song collection excursion. Two field notebooks from this trip were saved by writer and scholar Toros Azadian and handed to Koharik Gazarossian in 1943. The lament Aghchi Mert Merel A was the very first song in this collection that Gazarossian worked on. Thanks to Melissa Bilal, my dear friend who is an internationally recognized Gazarossian scholar, the inaugural Promise Chair in Armenian Music, Arts, and Culture at UCLA and also the director of the UCLA Armenian Music Program (a project that I was asked to start ten years ago at UCLA), I became aware of this work, and so we had the honor of premiering it in Los Angeles in the Spring of 2023, and later recording it for this project.

The renowned violinists Ani and Ida Kavafian, who play Kristapor Najarian’s A Tale for Two Violins, are those that gave its world premiere in Los Angeles in 2014. They certainly seem to dig right into this performance! There are some remarkable passages where both of them are double-stopping, enriching the sound; and indeed there is the contrastive power of the single folkish line. What’s fascinating is Najarian’s response to that line; or indeed the power of a single line against a drone (in the penultimate movement). The final movement is full of drama—this is indeed a tale of capture and escape. I like the idea that the titles suggest a story’s framework and leave the deals to the listener; I also like the way the music is expertly crafted. But this person is completely new to me! The programmatic nature of the music is more overt than any of the others on the set, would you agree?

This is another one of those happy stories of human and musical connections, dear to my heart. Kris (Kristapor) Najarian was an undergraduate violin student of mine at UCLA, a wide-eyed kid who loved not only Western classical music but also rock (he is really good in electric guitar) and folk (his father is an accomplished oud player, and his grandfather was a sought-after luthier of the oud, which is one of the traditional Armenian string instruments, plucked like a guitar). Midway through his violin studies, Kris added a composition major and graduated with both. Next thing I knew, he was in the Paris Conservatory studying with Eric Tanguy, and is now a composer in his own right. A Tale is Kris’ first widely successful work; it was a commission from the Dilijan Chamber Series and Lark Musical Society. The spectacular violinists Ani and Ida Kavafian (dear friends of mine) gave it a truly memorable premiere in Los Angeles a few years ago, and the rest is a history of repeat performances all over, and a universal acclaim by professionals and amateurs alike.

We dealt with disc four above when talking about Avanesov; so I wonder what’s next for your Armenian projects?

As I mentioned above, there is so much worthy Armenian music to document for posterity. My hope is that we’ll be able to issue sequels to the Modulation Necklace series about once every two years. I do have ideas, including potential commissions, but don’t want to jinx anything. Hopefully, when the time comes, we’ll be talking about the next project!

Also, a word about the recordings perhaps as, like the set’s documentation, they are superb. Were any of the composers present? Najarian and Avanesov are still with us, of course!

Did I mention earlier that I feel very lucky? The stars truly aligned, and the support that I had—creative, emotional, logistical—has been just superb. I do have to give a shoutout first and foremost to Sergey Parfenov, our lead recording engineer, editor, and a guru of sound and post-production. Sergey has been responsible for 270 minutes of recorded music on this set—it’s four and a half hours of music. Just imagine the amount of time and effort that it took to oversee that amount of material! I am also very grateful to my staff colleagues at the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music, where we are very lucky to have a state-of-the-art recording studio, one of the most coveted spaces in Los Angeles. Working with Dan Lippel, the creator and driving force of New Focus Recordings, has always been such a pleasure—this is our fifth project together. Dan is a great musician himself, and has human and musical standards that I admire. I am also very grateful to designers Marc Wolf and Irene Baghdasaryan for their beautiful creative solutions; I love both the printed and digital booklets.

Needless to say, the honor of choosing the performers and making music with them is what I cherish most, because once all the dust settles, those memories will stay with me.

Thanks so much for going through this rather long sequence of questions!

My pleasure!