Back to the Sources: Music from the St. Petersburg Society

Back to the Sources: Music from the St. Petersburg Society

Part I: Chamber Music

Sunday, November 19, 2023, 5:00 PM

Lani Hall, UCLA

Part II: Art Songs

Sunday, February 25, 4 pm

Lani Hall, UCLA

Performers

Repertoire

Poème, Op. 10 for cello and piano (1907-1910) (8’)

Alexander Krein (1883-1951)

Christopher Cho, cello

Brandon Zhou, piano

Aria, Op. 41 for violin and piano (1927) (8’)

Alexander Krein (1883-1951)

Adam Millstein, violin

Brandon Zhou, piano

SHORT INTERVAL (5’)

Piano Sonata No. 1, Op. 3 (1922) (10’)

Alexander Veprik (1899-1958)

Neal Stulberg, piano

Piano Sonata No. 2, Op. 5 (1924) (12’)

Alexander Veprik (1899-1958)

Neal Stulberg, piano

INTERVAL (10’)

Requiem for Piano Quintet, Op. 11 (1914) (13’)

Mikhail Gnessin (1883-1957)

Connie Song, viola

Christopher Cho, cello

Brandon Zhou, piano

Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano (Requiem for Our Lost Children), Op. 63 (1943) (12')

Mikhail Gnessin (1883-1957)

Adam Millstein, violin

Christopher Cho, cello

Brandon Zhou, piano

Program Notes

ABOUT THE ST. PETERSBURG SCHOOL

From both artistic and Jewish standpoints, pre-revolutionary Russia provided exceptionally fertile soil for the development of a new Jewish art music. The second half of the nineteenth century had seen the rise of musical nationalism in Eastern Europe, the spreading influence of Russian culture, the emancipation and movement of Jewish artists and intellectuals from the Pale to the cities, and the development of Yiddish literary and folkloric traditions -- all logical pre-conditions for a Jewish musical efflorescence.

Around the turn of the century, major Russian artistic figures began urging their young Jewish acolytes to mine their own rich sources of Jewish folk melody and tradition as material for their compositions. At the St. Petersburg Conservatory, the composer Rimsky-Korsakov dramatically threw down the gauntlet to his Jewish composition students thusly:

"Why should you Jewish students imitate European and Russian composers? The Jews possess tremendous folk treasures...Jewish music awaits its Glinka!"

At roughly the same time, 32-year-old Moscow composer and critic Joel Engel, spurred on by the influential cultural critic Stassov, organized the first public concert of Jewish folk music at the Moscow Polytechnic Museum, attracting a large and enthusiastic audience. This November 1900 concert was successfully repeated in St. Petersburg some months later, and the movement for Jewish national musical revival was born.

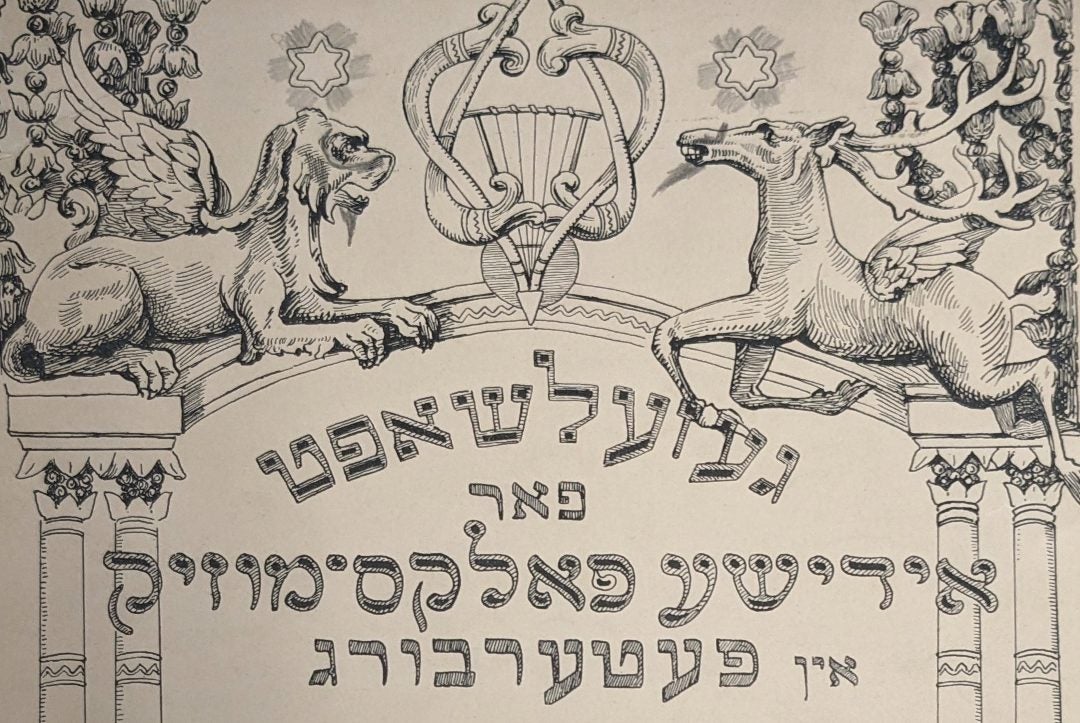

In 1908, this movement coalesced into an artistic union called the St. Petersburg Society for Jewish Folk Music. Despite its name -- imposed by a Czarist bureaucrat whose knowledge of Jewish music consisted of a folk melody he once heard at a Jewish wedding in Odessa -- the Society's goal was nothing less than the creation of an entirely new category of classical music: concert music infused with Jewish content.

The Society's founding charter stated:

"It is the aim of the Society...to work in the field of research and development of Jewish music (sacred and secular) by collecting folksongs, harmonizing them and by promoting and supporting Jewish composers and workers in the field of Jewish music. To achieve these aims the Society will:

a) help print musical compositions and papers on research of Jewish music;

b) organize musical meetings, concerts, operatic performances, lectures, etc.;

c) organize a choir and orchestra of its own;

d) establish a library of Jewish music;

e) issue a periodical dedicated to Jewish music;

f) establish contests and give prizes for musical compositions of a Jewish character."

Moving quickly to fulfill this charge, the Society's young composers began to freely adapt the collected folk materials, creating works in every conceivable genre and in strikingly individual musical vocabularies.

During its ten-year existence, the Society enjoyed extraordinary success. Four years after its founding, it numbered 389 members -- 249 in St. Petersburg alone -- and had established chapters in Moscow, Kiev, Kharkov, and Odessa. Its concert ensemble of singers and instrumentalists gave more than 150 performances throughout Russia, Germany, and Austria over a two-year period, and included the young performers Jascha Heifetz and Fyodor Chaliapin. It counted among its accomplishments the creation of hundreds of original solo, chamber, vocal, orchestral, ballet, theatre and operatic works, and quickly begat what Russian music historian Leonid Sabaneyeff would later term the "Jewish National School" of Russian composition.

Following the Society's abrupt dissolution after the 1917 Revolution, most of its members emigrated to Europe, the United States or Palestine. The Soviet regime had no interest in perpetuating the legacy of its Jewish composers, so the music ceased to be promoted or performed there. And although some of the Society's composers continued to write Jewish-inspired music into the 1920's, their dispersion, combined with the cultural repression of the Soviets, made it impossible to sustain the productivity of the movement, maintain ongoing performance traditions, or even preserve an archive of the music itself. Thus, this remarkable chapter in modern Jewish creativity remains under-explored.

Neal Stulberg