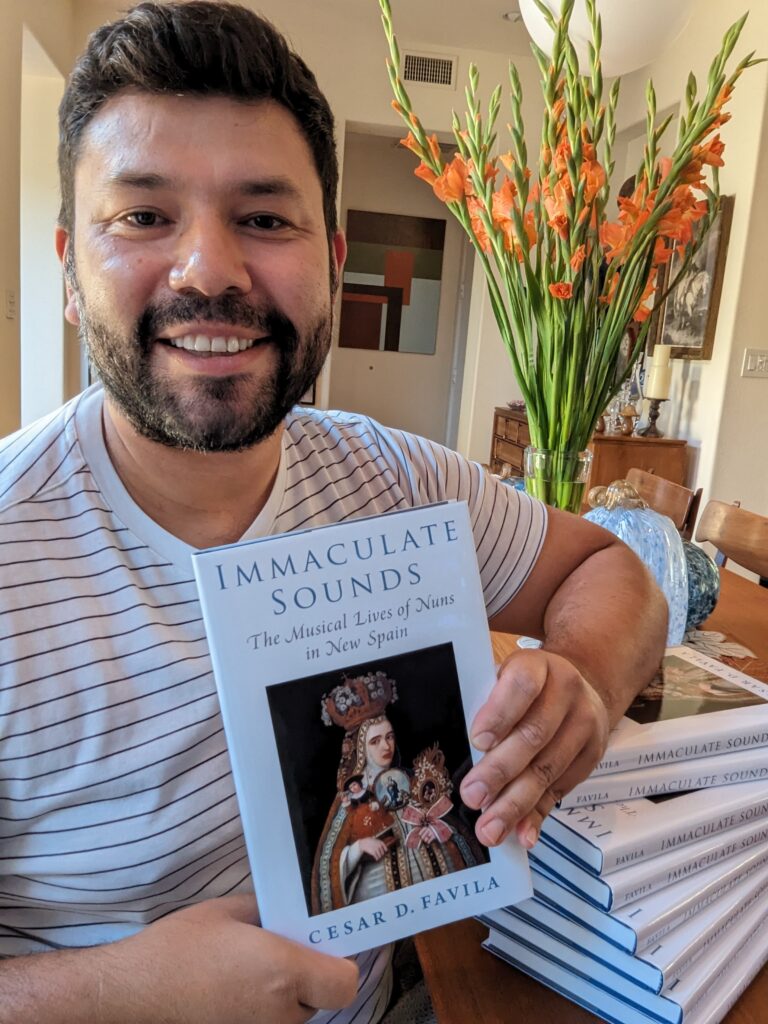

Cesar Favila, assistant professor of Musicology, has just published his first book. Immaculate Sounds: The Musical Lives of Nuns in New Spain breaks new ground in its imaginative approach to recovering the lives of women who sang devotional music in Catholic churches. Oxford University Press has published the book in hardback. The UCLA Library has partnered with the Toward an Open Monograph Ecosystem (TOME) to make the book available for use open access.

We sat down with Favila to talk about seventeenth-century polyphony, tales of spiritual communion, and his own Catholic upbringing in northern California.

This book is about music sung by nuns in New Spain. What made nuns’ music special?

Nuns’ singing was thought to be essential to salvation. My book traces the order of Immaculate Conception, the first group of nuns to arrive in New Spain from Europe, and the convents that sprung up afterwards throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It was widely believed that women had to be locked away in these convents and preserved for singing because that singing was essential to saving people’s souls. I connect this belief to a really unusual doctrine of the Virgin Mary’s essence which basically held that her soul was conceived without original sin from the beginning of her existence in order that she could be the mother of Jesus Christ. This made Mary a kind of co-redeemer.

How widespread was this belief?

It was not widespread. It wouldn’t become official doctrine until much later. But the Spanish were obsessed with this doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, as it was called, even though it was not official dogma of the Church. It is one of the reasons that this was the first order of nuns to arrive in New Spain, to push the doctrine forward.

Cesar D. Favila writes with compassion and curiosity, and with a love of storytelling that brings his material to life…

Laurie Stras, Professor Emerita of Music, University of Southampton

So people would come to church to watch the nuns sing as a way of saving their souls?

You would come to church but you wouldn’t see the nuns singing.

You wouldn’t see them?

They were in the back, they were kept behind grates, the choir was always shrouded, and it raised all kinds of opportunities for misbehavior. For instance, people might try to talk to the nuns through the grates and ask them to sing a special hymn.

So, no requests?

That’s a big no-no! The nuns were constantly being watched, and their obedience was constantly being tested. You know, there’s a great story that I recount in the book about a nun, a very important nun, she has several biographies written about her. And one day, the reverend mother and her confessor tested her obedience by telling her she will not be allowed to take communion on a particular day. So what happens? Communion flies up to her. She’s in the back, praying, and the Eucharistic wafer flies up from the alter and somehow ends up directly in her mouth.

She gets communion anyway.

Yes, but the descriptions that are given of this are important, because it is a spiritual communion that she gets—a perfect, spiritual communion. And one of my arguments in the book is that nuns were essential to spiritual communion. Often times people would be denied communion by their confessors, and they were told to sit and imagine receiving sacramental communion, consuming the wafer. That is spiritual communion, deeply imagining physically eating the communion bread believed to be the Body of Christ. I argue that music was a form of spiritual communion. God was in the notes, as some sermonizers taught, and the notes, as sound, could penetrate you. It is a way of experiencing God.

Favila discloses an expansive, new world of convent culture, abounding in fresh musical, visual, literary, biographical, and bibliographical information.

Craig A. Monson, Paul Tietjens Professor Emeritus of Music, Washington University in Saint Louis

You actually visited a nuns’ convent in Toledo, Spain, didn’t you?

I did! I did research in the Motherhouse of the Conceptionist order in Toleedo. I was able to go to the convent’s locutorio, which is their parlor, and see the nuns through the grate. Two of them came to meet me there, and the first thing they did was greet me with “Ava María purísima,” and I immediately replied “sin pecado concebida.” It was a phrase I was familiar with from my Catholic upbringing, “Hail purest Mary, conceived without sin.” But the nuns were thrilled that I knew their salutation, even though I didn’t really know it was their salutation.

You grew up Catholic?

I did. My grandparents immigrated from Mexico. They were field workers, and they came to California for a better life. My grandparents were deeply religious, and the Church was their education. My grandparents taught catechism class, and my grandfather eventually became a deacon. I grew up with this tradition, and I was fascinated by sacred music.

In fact, when I got to college, the only thing that vibed with me was the music history class, where I learned about Gregorian chant and its role in Western music notation. I thought, “I know what a Gloria is, I know what a Kyrie is, I know something!” It can be hard for a first-generation student, like myself, to connect personally with subjects in college and it was music history that helped me.

So music helped you acclimate to college?

It was my intellectual grounding. I was always fascinated with the organ. My parents encouraged me, they got me lessons, and I got to be good at playing the organ in church. So I would play organ for weddings, funerals, and for quinceañeras—honestly, it helped me pay for college. I was making $100 per service and eventually raised my rate after I found out how much people paid for wedding cakes. How else as a student are you going to make that kind of money?

So music helped me in more ways than one, I guess.

Do you still play the organ?

Whenever I can!