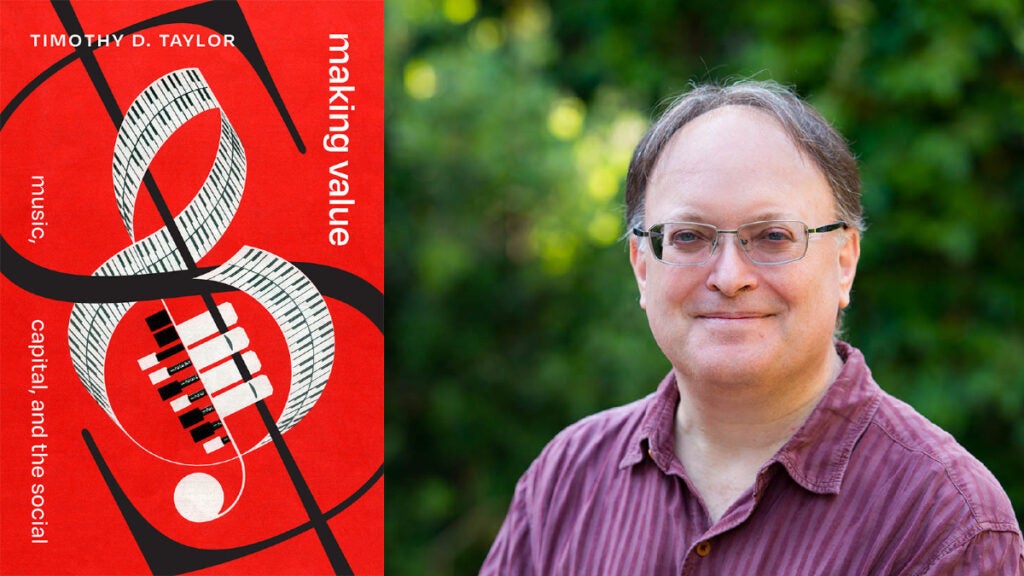

Tim Taylor, professor of ethnomusicology and musicology at The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music, has always been curious about how we assess the value of music. The author of over 50 articles and a shelf of books, Taylor has explored music and capitalism, global pop, western music in the world, and more.

His new book is Making Value: Music, Capital, and the Social, published by Duke University Press. Taylor looks at music through the lens of value, an anthropological and economic theory that considers music not solely in terms of money, but also not strictly on its own, aesthetic terms. For research, he went in depth into various historical moments—the rise of the virtuoso in nineteenth-century Europe, traditional Irish session music, the indie rock scene in the Echo Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, and more.

* * *

Your book is about making value, but it strikes me that it is really about music’s meaning. This is a question that some people would reserve to the field of aesthetics, or perhaps cultural criticism. But you begin with the theoretical proposition that the best way to get at that question is to use anthropological value theory. What is it?

It goes back to Clifford Geertz, the anthropologist. What Geertz did was re-orient anthropology away from scientific approaches and make it more humanistic. Geertz redefined culture as systems of meaning for the people in that culture.

For me, this idea of “meaning” was compelling. It seemed to me to be absent in a lot of musicological and ethnomusicological work, where we describe a musical ritual, say, but we don’t necessarily talk about why it is meaningful for the people who participate in it.

So, your approach is essentially Geertzian?

Yes, although I found Geertz to be a little too idealist, in the sense that he excluded things like money or economics. And I’m interested in economic questions. Using anthropological value theory is a way of getting at both these things. An anthropologist at the University of Toronto, Michael Lambek, writes that there’s a difference between playing a violin for money and playing it for pleasure. There’s value in both those activities, but they’re different kinds of value. The anthropological concept of value lets you talk about both.

You find some very interesting sites for exploration of the concept of value, everything from the rise of the nineteenth-century virtuosos in Europe to the Echo Park indie rock scene in east Los Angeles. I have to ask—what drew you to the indie rock scene?

Well, we’re used to thinking of music as a commodity, or we talk about how capitalism commodifies music. But the indie rock scene wasn’t operating that way. One musician I spoke to, Michael Fiore, in a band called Criminal Hygiene, delivered pizzas to pay the bills. And he told me that his band was going on tour, and I asked him what he was going to do about his job. He told me that the owner was really supportive of the indie music scene and would hold the job for him while he went on tour. That scene wouldn’t work without patrons like that.

Most of the people I interviewed described a scene where they would make maybe thirty-five or forty dollars a gig—if they were paid at all—and maybe get a free beer. They would think about tours in terms of whether they could cover gas money and food.

And that’s not capitalist?

No, it’s not. They’re not producing profit for a capitalist, like a record label owner. There’re all these things that anthropologists call generalized exchange (giving and receiving between strangers, like crashing on another musician’s floor while touring) and generalized reciprocity (ordinary sorts of giving and receiving between friends and family). You need these things to make the scene work, because there’s basically no money in it. If the scene is going to sustain itself, it has to do so with these noncapitalist strategies.

But in your book you talk about capitalism creating the indie rock scene, or perhaps—to put it better—that capitalism is responsible for creating it.

Capitalism relies on people working on the margins, and those margins are created by capitalism. The music business is the capitalist center, and some people are trying to get in. Most of the time, though, people fail. We don’t think about it that way, because our news is dominated by people like Beyoncé and Taylor Swift. Most of the musician s I talked to just wanted to make a living, they didn’t want to be huge.

Why does capitalism rely on these people in the margins?

They create new sounds; they bring new talent. But capitalism also destroys these scenes.

Explain that.

Getting paid forty dollars a gig doesn’t support a scene. And some of the support structures in the Echo Park scene are now gone. Origami Vinyl, a major hub in this scene, closed a few years ago. People age out. The capitalist music industry vacuums up what it wants and everyone else dries up or moves on.

Is there a different way?

There are plenty, we just don’t pay attention to them.

Like what?

My parents sang in a church choir for years. They were never paid. The choir director was paid, but no one else was paid. I play Irish traditional music every Sunday in a bar in Long Beach. Occasionally I get paid. Payment rotates among the core musicians. I show up whether I’m getting paid or not. Some people do rely on that money, but they don’t make a living from it. Musicologists and ethnomusicologists don’t pay enough attention to those kinds of musicians, I think.

The British anthropologist Ruth Finnegan wrote a book called The Hidden Musicians. It’s an ethnography of amateur musicians in the English town of Milton Keynes. To my knowledge, no study like it has been conducted in the U.S. We tend to think that the only musicians worthy of study are those who are exceptional. But I think these other musicians are worth our attention, too.

Like the musicians in an Irish bar?

Just like those musicians.

How long have you been playing Irish music in Long Beach? Was Irish music something you grew up with?

I actually only listened to classical music growing up, I loved it. I started on piano, then played the clarinet and the cello. The cello faded away because I was in a small town and we didn’t have an orchestra or anything. I went to college, double majored in music and environmental studies, then went on to music school to study clarinet. And then I went to the University of Michigan to get a Ph.D. Michigan had this exchange and fellowship deal with the Queen’s University of Belfast, where there was a famous ethnomusicologist named John Blacking. I applied and I got it. So, in the fall of 1988, I took my clarinet to Ireland, I played in the orchestra, and I did all my usual nerdy classical music stuff.

And one night, I went with some of my friends to a pub, and there were these people sitting around playing Irish music, drinking, laughing. I had never seen—as a classical musician—I had never seen people playing music for fun. Not that it wasn’t fun to play in orchestra, but it was work and serious, and you have to be really good and you have to practice. This was different.

So, I learned the tin whistle, which has the same fingering as the upper register of the clarinet, so I could play it immediately, though it took a lot longer to learn the style and learn tunes.

You’ve been playing it ever since?

With some hiatuses here and there, but yes.

And you have a talk about traditional Irish music sessions in your book.

Yes. We call them sessions, but they aren’t like jam sessions. With Irish traditional music you have to know the tune or you don’t play. Tunes are all for dancing, although we rarely have dancers. Tunes are only eight or sixteen bars. The convention is that you play a tune three times, then you switch to another tune and play it three times, then you switch to another tune and play that three times. That gives you about five minutes of music, which is enough time for the dancers to do their thing. Even though there aren’t dancers at most sessions, the convention of playing a tune with repeats and segueing to another remains, it’s one of the arts of playing this music.

At sessions, musicians defer to better musicians and to older musicians. And the conventional academic wisdom is that this is about maintenance of hierarchy—people keeping or attempting to improve their position in the pecking order. But no one says, ‘I’m going to the session to maintain my place in the hierarchy!’ People go because it’s fun! What became clear to me in working on this is that people go to these sessions to maintain sociality. They go for the community. What people value in these sessions is sociality.

Let’s shift gears here. You talk about the rise of the virtuoso musician in nineteenth-century Europe. But you don’t talk about it as the rise of a certain phenomenon, or an improvement on playing. You describe it as capitalism’s disciplining of music.

I think a lot of important historical questions about western European classical music haven’t been asked, we have tended to focus closely on music and less on culture/history/the social. Why did tonality “break out” at the beginning of the seventeenth century? Why did it become the dominant musical system in the west for hundreds of years? That’s not only a technical question, but we treat it that way. I argued in my book Beyond Exoticism that it was because of the rise of European colonialism in the seventeenth century. Tonality does the same thing as colonialism: It creates centers and margins. And we talk about tonality using spatial terms, how composers explore different tonal regions, how they move from one to another and back.

So, why did the modern virtuoso arise in the nineteenth century? There were virtuosi before that, especially with singers. But the famous, instrumentalist virtuoso doesn’t really arise until the nineteenth century. I argue that it is an effect of what Marx rather famously called alienated labor.

Well, when I think of alienation, I think of the division of labor, about how a factory worker, unlike a craftsman, is no longer making a complete product. Rather, the factory worker just completes one repetitive task. How does that translate to the concert hall?

Well, music used to be played in salons, in more intimate settings. Or in the public square or the pub. Now it is in these massive concert halls and musicians are performing to hundreds of people in a for-profit enterprise. And there are all these conventions that keep the musician and the audience separated. For instance, you aren’t supposed to applaud in classical music concerts until the very end of the show, no matter how great a particular part of the performance. Being a flamboyant performer allows you to reduce that sense of alienation, to reach out to your audience. This kind of virtuoso behavior has value for audiences, a sort of capitalist value that exists alongside the more obvious capitalist economic value.

And notice how the rise of these performers who command big audiences also coincides with the rise of a notion of aesthetics, of ‘art for art’s sake.’ You might think about that as a reaction to these new, huge for-profit concerts. But it isn’t. It’s a coequal part of it.

Is that how capitalism disciplines music?

Well, yes, but let’s be careful. Capitalism is a form of social organization, it doesn’t do anything—people do. So, sure, capitalism disciplines music because, as a hegemonic social form, it disciplines all forms of the production of value. So, one of the things I’m interested in in that chapter is why people like Franz Liszt and Niccolò Paganini herald a new kind of performer. The scaling up and commodification of concerts is key to this. So is the rise of the music manager, which I talk about in another chapter. And so is the rise of an aesthetics that isolates art and artist from all of this vulgar money.

But aren’t we always trapped by the dominant economic mode of production, and today by capitalism? Is there any way out of it?

Well, capitalism is hegemonic, but it’s not total. I still go back to Raymond Williams and his concept of hegemony as always being in flux, with people constantly opposing it, finding alternatives, resisting. But it’s not as if those people outside the mainstream music business are making noncapitalist music. They are often making music that sounds like the music produced by the mainsream music business. And music managers drew my attention because they act as a bridge, ushering people into the world of the capitalist music business. These are all processes that I think we academics need to pay more attention to.

I don’t know if I’d say there’s a way out, but I would say that there is plenty of music being made outside of, and beyond the interest of, the mainstream music business, like in my Irish bar, in churches, in people’s homes and garages. It may not be considered to be “great music,” in any conventional sense, but it still has value to the people who make it.