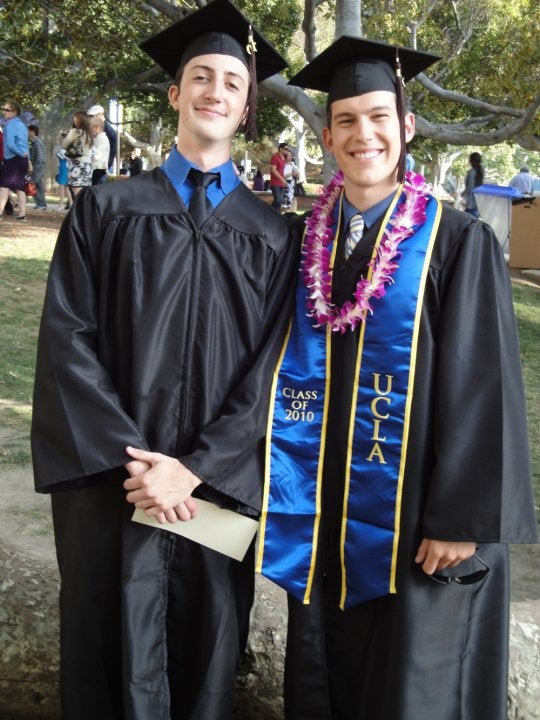

William A. Baker graduated cum laude from The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music in 2010 with a bachelor’s in music performance, studying euphonium and bass trombone. He earned a master’s degree at Northwestern University and spent several years in Chicago before relocating to the San Francisco Bay Area, where he played frequently with the San Francisco Symphony. In 2024, Will Baker was appointed bass trombonist of the Lyric Opera of Chicago Orchestra.

Will’s musical trajectory is not so simple, however. Along the way to winning a full-time orchestral gig, he changed his primary instrument from euphonium to bass trombone and commissioned a concerto. He spent time working the desk at a gym and commuted to play in regional orchestras.

Will is currently preparing to leave San Francisco and move back to Chicago. We chatted about his time at UCLA, how he started down his musical path and making it as a working musician.

* * *

Congratulations on winning the position with Lyric Opera. You lived in Chicago during graduate school and after. Are you excited to be going back to Chicago?

Yes, I loved my time in Chicago. That was where I became an adult, where I first became self-sufficient as a working musician and where I proposed to my wife. And I am still close with my friends and teachers from Northwestern.

Talk a little about your first experiences as a working musician. What was it like performing in and around Chicago?

I had almost no orchestral work in Chicago! I had a couple students close to Northwestern, and some blues gigs in town, but I drove all over for orchestra gigs. The first regional orchestra I subbed with was in Kenosha, Wisconsin. My first day job after grad school was working the front desk at a gym. I needed something consistent, and it was very flexible. The people who worked there were very artsy—videographers, photographers, actors, and we were all very supportive of one another. We were a close-knit community.

About a year after I graduated, I won a position with Orchestra Iowa, in Cedar Rapids. A year after that I won a position with the Des Moines Symphony. Cedar Rapids was about four hours from Chicago and Des Moines was about five. Those two contracts and teaching made up the backbone of my career. Add in some occasional gigs with Kalamazoo, Lansing, or Detroit, and I was busy.

Let’s take you back to your time at UCLA. In your first year, did you have any inkling of what the life of a professional musician would be like when you graduated?

I had no clue. I didn’t really think I would end up as a musician. I thought I’d play music, but probably go into business or accounting. My dad’s a CPA. I thought I would ride music into school, then maybe go to business school.

Why did you choose UCLA?

UCLA fit my vision perfectly. It was big enough that If I met someone I didn’t like, I could say ‘happy trails’ and meet ten new people the next day. It was far enough away from home that my parents couldn’t surprise me, but close enough to drive home in a day. It also had the best music school out of all the UC’s. I came to study euphonium. But I wasn’t super focused on becoming a professional musician at that time.

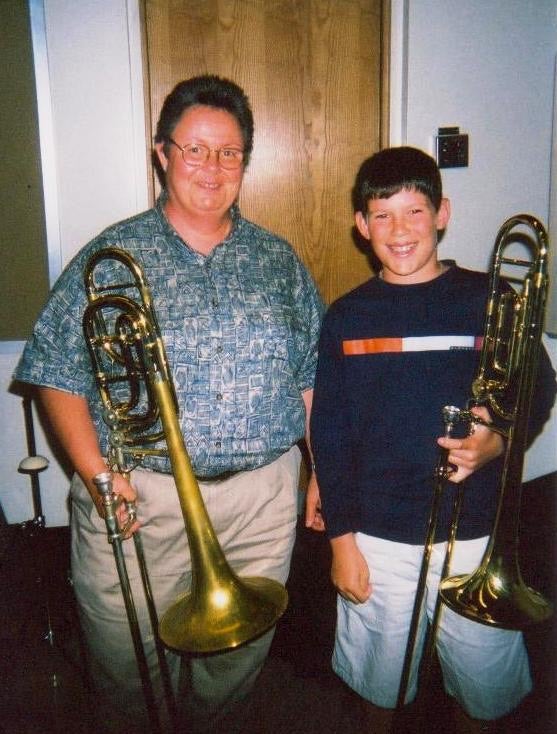

You started on Euphonium. How did you pick up the bass trombone?

I had always played trombone, but only in jazz band and wind ensemble. I’d never played in an orchestra before college, I don’t think I’d even been to an orchestra concert. My freshman year, the UCLA Philharmonia programmed Leoš Janáček’s Sinfonietta, which has two huge fanfare movements that call for extra brass players, including two euphoniums. The word came down from above that I was needed in the orchestra this week, and so I said, ‘sure.’ Playing the fanfare was super fun. But when the strings and winds played the middle movements, my jaw hit the floor. The sounds were amazing. It was like being in a movie. I knew I had to get back into an orchestra, It was like being hit by a lightning bolt.

There I was at the very end of the long row of brass players on stage in Schoenberg Hall. I remember looking down the row at the trombones, and thinking ‘junior, junior, master’s—there’s no way I’m getting into this orchestra as a tenor trombone player.’ But then I saw that the bass trombonist who was a senior, and I knew there were no underclassmen vying for his spot. I thought, ‘that’s how I’m getting in.’ I checked out a bass trombone that week and starting tinkering on it and enjoyed it. My sophomore year I got into the UCLA jazz big band and the UCLA Philharmonia.

You were off to the races.

I certainly started to dream about playing music for a living. My sophomore year, a new tuba and euphonium teacher arrived—Pat Sheridan. At one point, Pat said to me, ‘you’re doing great. You can keep doing what you are doing and be the best euphonium player at UCLA. Or, you could work really hard and you could play music for the rest of your life.

Nobody had ever said anything like that to me until Pat. And I trusted him. He was an international soloist and a great teacher. If anyone knew, he knew, so I started dedicating myself.

You commissioned a bass trombone concerto, right?

I did.

How many bass trombone concertos are there in the rep?

I don’t know. (Laughs.)

What led you to the commission?

It was a little bit out of necessity. I got a gig as an artist-in-residence with the Southeast Iowa Symphony and I needed to select something to perform with the orchestra. So I sent a handful of options to the director. He really wasn’t feeling enthusiastic about the solos I shared, so I pitched to him the idea of commissioning a new work by a composer I knew personally. He trusted me and went with it.

The previous summer, I had met the composer Robert Tindle while on faculty at a summer brass camp. He had just won the camp’s composition competition, and I loved playing his music In the faculty brass ensemble. So I contacted him and commissioned the concerto, and he wrote At Sixty Miles an Hour. It turned out to be a great piece of music that showcases the ensemble, not just the soloist. It’s really fun to play.

You played that piece at UCLA, didn’t you?

Yes, I performed At Sixty Miles an Hour in Schoenberg Hall in 2018 with the UCLA Wind Ensemble.

That was the west coast premiere?

Actually it was the world premiere of the version scored for wind ensemble. I premiered the version for orchestra with the Southeast Iowa Symphony two years earlier.

How did that come about?

At the Midwest Band Convention, which is held in Chicago every year, I managed to corner the UCLA Director of Bands Travis Cross, and gave him my elevator pitch. He loved the idea and went for it. Working with him was a great experience. The Wind Ensemble sounded great, and we got a great recording out of it which you can hear on YouTube. My family and friends came from all over California to hear the performance.

You played with the San Francisco Symphony?

I did. I never won a position, but they hired me very consistently for the last few years, and it was life changing. It was kind of like a real-world doctorate in orchestral performance. You can learn so much working with conductors like Esa-Pekka Salonen, John Williams, and Jaap van Zweden. The musicians are so good, they are demonstrating in every moment how to play with a world class sound in the right style. They are also very collaborative and helpful and encouraging. I often carpooled with the second trombonist, who lived just a few miles away from me. He’s a great guy, a great dad, and we bonded over experiences with our kids. Sometimes at work he would lean over and say ‘hey Will, try this out.’ It was always great advice.

What advice would you give a UCLA student who is looking to make it in the musical world?

A few of things. You’ll need strong fundamentals on your instrument, so you must build a personal routine that helps you improve every day.

Also, get out there and listen to music. Hearing concerts live is a powerful experience. Go listen to the LA Phil. Go listen to the UCLA Philharmonia. Go listen to everything. And this applies to any genre. If you’re into jazz, seek out those concerts.

Find the people that have the work that you want, and take lessons with them. Everyone, whether they think they like it or not, likes teaching, likes passing on their knowledge. If you come prepared and on a mission, they are going to notice that and feel that, and then they will want you to succeed. And they will often try to help you out. They’ll point out the potholes to avoid and help you find new paths.

Lastly, try to make your own opportunities. Create collaborations, commission new works. There are a limited number of orchestra chairs out there, so … go and make YOUR thing.