Classical music has for too long occupied a tacitly-acknowledged white space, seemingly hostile to voices from outside its European origins. So how do we decolonize classical music?

George E. Lewis, Edwin H. Case Professor of Music at Columbia University, has some ideas.

The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music will host a residency of Lewis in the first week of November, 2022. Lewis’s residency will feature two major public events: a lecture on Thursday, November 3 at 4:00 p.m. in Royce Hall 314, and a concert on Saturday, November 5 at 8:00 p.m. in Schoenberg Hall. Both events promise ideas and action on Lewis’s suggestions on upending the status quo.

Composer, musicologist, and winner of MacArthur and Guggenheim fellowships, Lewis has spent his life pushing creative boundaries. He was recently named the artistic director of the renowned International Contemporary Ensemble, a leading new music organization based in New York.

“George is the very reason I went into academia,” said Nina Eidsheim, professor of musicology at UCLA. “I met George via workshops he offered as part of a residency at CalArts after he won the Herb Alpert Award in the Arts. It was the first time I’d met somebody who was both an artist and a scholar and I remained in the U.S. to do a doctoral degree with him at UCSD.”

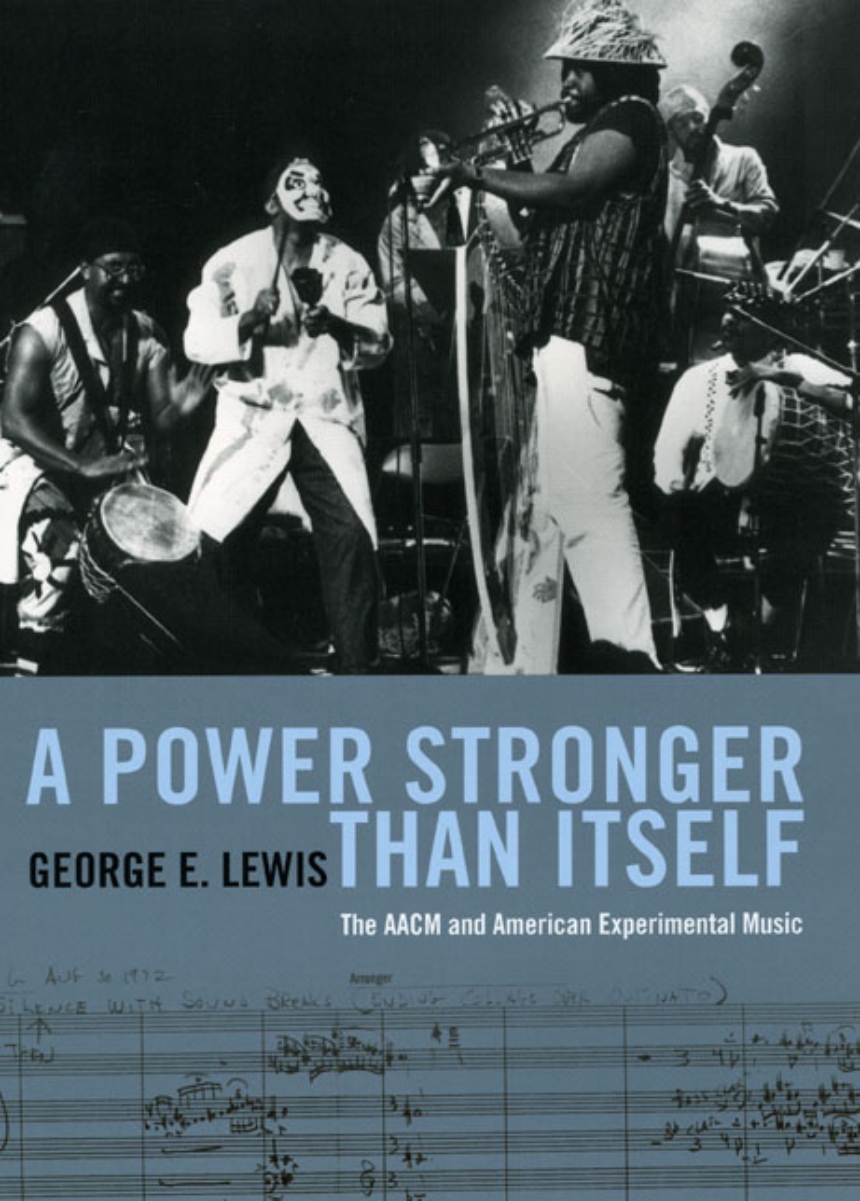

Lewis’s work as a musician and composer began on Chicago’s South Side, where he joined the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) at the age of 19 in 1971. The group’s eclectic compositions and musical tastes extended beyond the artificial frontiers normally assigned to Black music. As Lewis himself put it in his book A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music, the organization retained a Black working-class perspective while embracing radical alternatives to mainstream Chicago jazz and blues.

The resulting avant-garde music was hard to categorize. As Lewis has commented, the cultural urge to label Black music as “improvisational” and white classical music as “experimental” never really captured the essence of either, and was doubly bound from the start by racial and class perceptions rooted in history and prejudice.

Lewis’s November 3 discussion, “New Music and the Heterogeneous Sound Ideal,” addresses directly the question posed by African American composer Olly Wilson about what precisely made music (any music) “art” rather than “entertainment,” and what, if anything, defined the aesthetic of Black music. Wilson identified a shared conceptual approach within Afrodiasporic music-making. Lewis picks up Wilson’s threads to identify aesthetic directions that appear within Afrodiasporic classical music since 1960.

“When you think about the Black music tradition, there is a big emphasis on creating a unique sound. No one wants to sound like someone else,” said Cheryl Keyes, professor of ethnomusicology and global jazz studies, and chair of the African American Studies Department at UCLA. “George’s own music is evidence of his immense creativity and avant-garde style.”

Classifying Lewis’s own music can be tricky. He has written a broad variety of experimental music. He began working with computers in music in the 1970s. In the 1980s he began developing a non-hierarchical, interactive musical environment called Voyager. The computer program creates a dialogue between improvisers and a computer-generated “improvising orchestra” that analyzes and reacts to the improvisers in real time.

An important step in decolonizing classical music, as Lewis recently opined, is encouraging ensembles to commission new music from a diverse array of composers. The Bent Frequency Duo, a new music ensemble devoted to the avant-garde, will perform a November 5 concert at Schoenberg Hall featuring new commissions by Lewis, African American composer Alvin Singleton, and Singaporean+ composer emily koh.

“The Bent Frequency Duo has commissioned over 40 new works of music in the last nine years,” said Jan Berry Baker, co-artistic director of the group (with Stuart Gerber) and professor of saxophone and vice chair of the Department of Music at UCLA. “Bent Frequency has always sought to include artistic voices from diverse communities and use its music making and art as a catalyst for social change. In 2018, we decided to make explicit what we had been doing for years.”

The Bent Frequency Duo named its 2018-19 season “Amplify,” and devoted it exclusively to performing music composed by women, people of color, and other composers who have historically been underrepresented in classical music. The season’s success led to a continued theme. Its 2019-20 season “Re-Amplify” was followed by “Sustain” in 2020-21 and “Renew” in 2021-22. Baker and Gerber built each season on the promise that more than 80% of programming would be dedicated to decolonizing classical music.

In 2022, Bent Frequency celebrates its twentieth anniversary. Its new season, “Resonance,” strengthens connections between the ensemble and its audiences. Its goal is to amplify the deeper meaning that music has to each of us individually and also to stress how important artistic voices resonate with and reverberate within our communities.

It is a goal shared by Lewis, whose International Contemporary Ensemble also celebrates its twentieth anniversary this year.

“You and I need to invent a new, incarnative ‘we’ that understands contemporary music not as a globalized, pan-European, white sonic diaspora, but more like the blues, practiced by the widest variety of people in many variations around the world,” said Lewis. “If this new ‘we’ can embrace ‘our’ future, even with all its turbulence, we can reaffirm our common humanity in the pursuit of new music decolonization.”