by Daniela Smolov Levy

The flourishing of theatrical, literary, and journalistic culture in Yiddish, also known as mame-loshn (mother tongue), in early twentieth-century America reveals the persistence of Old World linguistic and cultural attachments even in the face of a powerful English-language mainstream. As we have seen in this series of posts and related lectures, the Yiddish press played a key role in promoting opera among its readers, who were an important target audience for opera producers of all stripes. But it might still seem surprising that this largely working-class, relatively unassimilated public of recent immigrants would have been considered likely to be interested in opera. Assimilated American Jews were of course well-known for their operatic involvement as not only patrons but also producers and managers at the highest levels, including figures like Oscar Hammerstein and Metropolitan Opera-affiliated personnel including Maurice Grau, Heinrich Conried, and Otto Kahn. But how much did the less assimilated Jewish public really engage with opera?

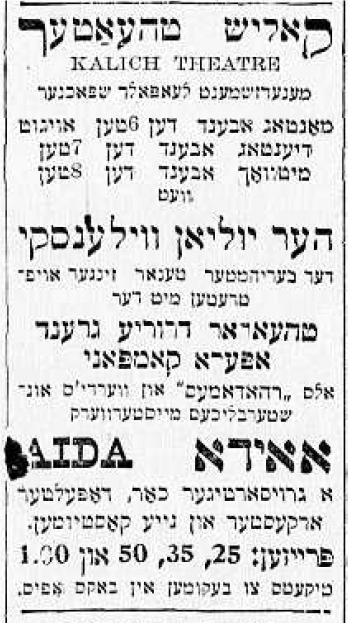

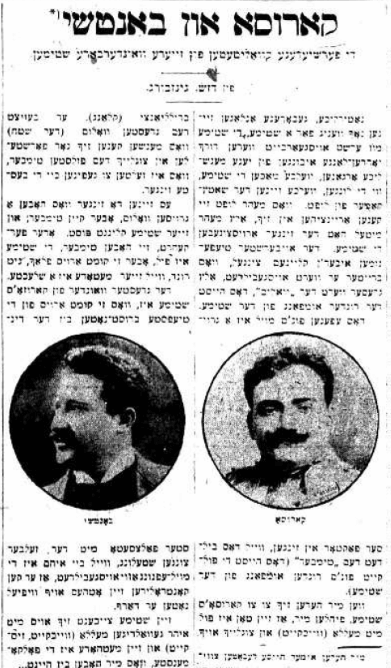

Evidence that they engaged with it a great deal appears all over the cultural landscape. European-language opera performances given by people like Abramson, Hammerstein, Medvedieff, and the Zuros formed only a small part of the Yiddish-speaking public’s exposure to opera. The Yiddish press also reported on English-language popular price opera, including the Century Opera and the all-Black Theodore Drury English Grand Opera Company. Tenor Julian Wilensky – who had sung opera in Yiddish translation with Moyshe Hurwitz’s troupe in 1904 – even joined the Drury company for a few performances.

Yiddish speakers who didn’t attend the opera would still have heard operatic music in many other contexts, high and popular, secular and sacred. As we have seen, the operatic style, including quotations from famous operas, was interwoven into Yiddish theater music, and sheet music of easy piano arrangements of operatic favorites were also marketed toward the theatergoing public. In addition, cantors of the period sang in a style highly reminiscent of opera, both with respect to voice production and in their virtuosic embellishment techniques. Numerous cantors sang operatic arias in concert and on recordings, with no fewer than three – Yossele Rosenblatt, Gershon Sirota, and Joseph Schmidt – earning the title of the “Jewish Caruso.” Opera’s dangerous allure for cantors was also frequently discussed in Jewish circles. [1]

Yiddish speakers also heard opera in concerts given by musicians like Joseph Winogradoff, who followed an extensive European operatic career with joint recitals all across America during the 1920s that mixed operatic excerpts with classical instrumental music, Yiddish folk songs, recitations from the Yiddish theater, sacred music, and even jazz. (Winogradoff also performed in the Yiddish theater and later became a cantor.)

Opera cropped up in unambiguously popular contexts, too, such as at a picnic and concert in a public park in June 1902 featuring excerpts from Faust, Carmen, Demon, La Juive, and Halka.

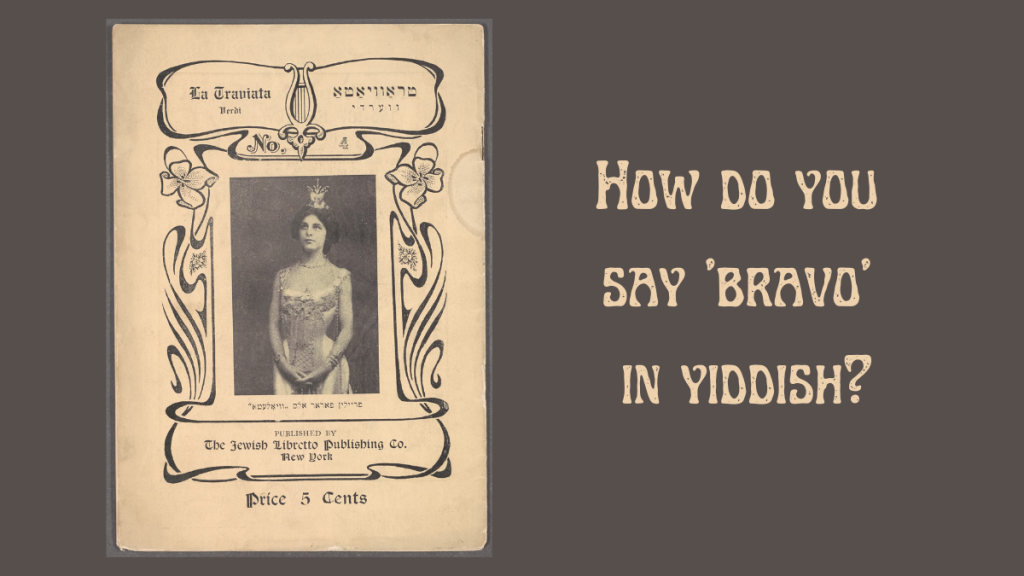

In addition to the copious reporting in newspapers on all things operatic, Yiddish books, magazine articles, and libretti reveal the extent of Yiddish speakers’ exposure to the genre. The emerging media of recording and radio further integrated opera into immigrants’ cultural experience. [2]

This prevalence of opera among Yiddish speakers can partly be explained as a simple response to demand. As we have seen, opera already held a special attraction for Yiddish-speaking immigrants from cultures with a strong opera going tradition. Popular price opera companies in particular targeted the many opera lovers in this group who couldn’t afford to attend elite-oriented opera or felt marginalized in that context.

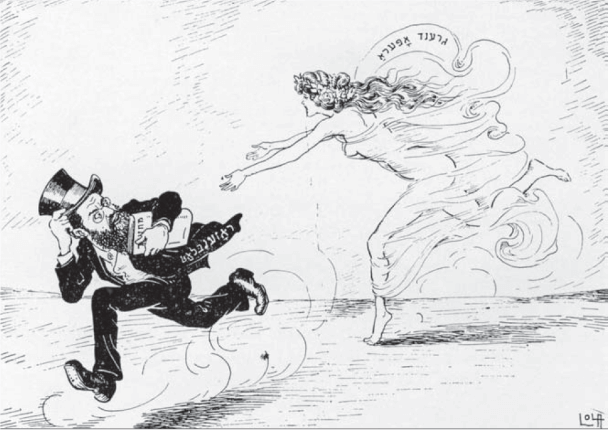

Opera’s presence in the Yiddish-language sphere also reflects its appeal as a tool of cultural uplift: opera was widely seen by both Jews and non-Jews as an elite art form that could confer edification, refinement, and sophistication. This Progressive Era belief in high culture’s power to uplift audiences paralleled the ideals motivating the turn-of-the-century reform movement in the Yiddish theater, in addition to dovetailing with the value of oyfklerung (enlightenment) that was part of the Socialist ideology central to Yiddish-speaking circles. The free lectures and programs offered by organizations like the Educational Alliance and the Board of Education further reveal an institutional commitment to uplifting Jewish immigrants through high culture.

Opera’s resonance for Yiddish speakers can thus perhaps be attributed to its ability to reconcile the Old World with the New. It straddled tradition and modernity by simultaneously representing familiar European culture on the one hand, and prestige and refinement in the American mainstream on the other. Consumption of opera could therefore be as much a marker of assimilation and acculturation as of adherence to European roots.

The case of opera aimed at Yiddish-speaking audiences further reveals the complicated and symbiotic relationship between the high and popular cultural spheres of the early 1900s. Although in theory, the categorizations of musical genres as highbrow or popular had become relatively fixed and widely recognizable by the turn of the twentieth century, in practice, these genres mixed freely in multiple cultural spheres. This suggests that a similar musical aesthetic pervaded these various contexts, despite differentials in prestige and target audience.

Although this exploration of opera focuses on a single ethnic group in a circumscribed time period, it can also shed light on the broader topic of the diverse ways in which immigrant communities deploy culture to negotiate the tension between the pull of assimilation and the desire to preserve a unique cultural heritage.

NOTES

[1] On the topic of cantors and opera, see the work of Mark Slobin, Jeffrey Shandler, and Judah Cohen, among others.

[2] For more on this, see Daniela Smolov Levy, “Grand Opera for Yiddish Speakers in Early Twentieth-Century America! Who Knew?!”, Digital Yiddish Theatre Project (May 2019)

Note: This post is the last in a five-part series based on the five lectures I am giving for the Lowell Milken Center for Music of American Jewish Experience at UCLA (via Zoom) between January and May 2022, “How Do You Say ‘Bravo’ in Yiddish?: Italian Opera for the Yiddish-Speaking Masses in Early 20th-Century America.” You’ll find recordings of those lectures on the YouTube page of the Lowell Milken Center.