When Regina Carter was a young girl growing up in Detroit, her mother sometimes took her to work with her. As they drove to the elementary school where she taught, Carter’s mother pointed out the different neighborhoods. “This one is ‘Black Bottom,’ and this is ‘Paradise Valley,’” she would say, as Carter looked out the window.

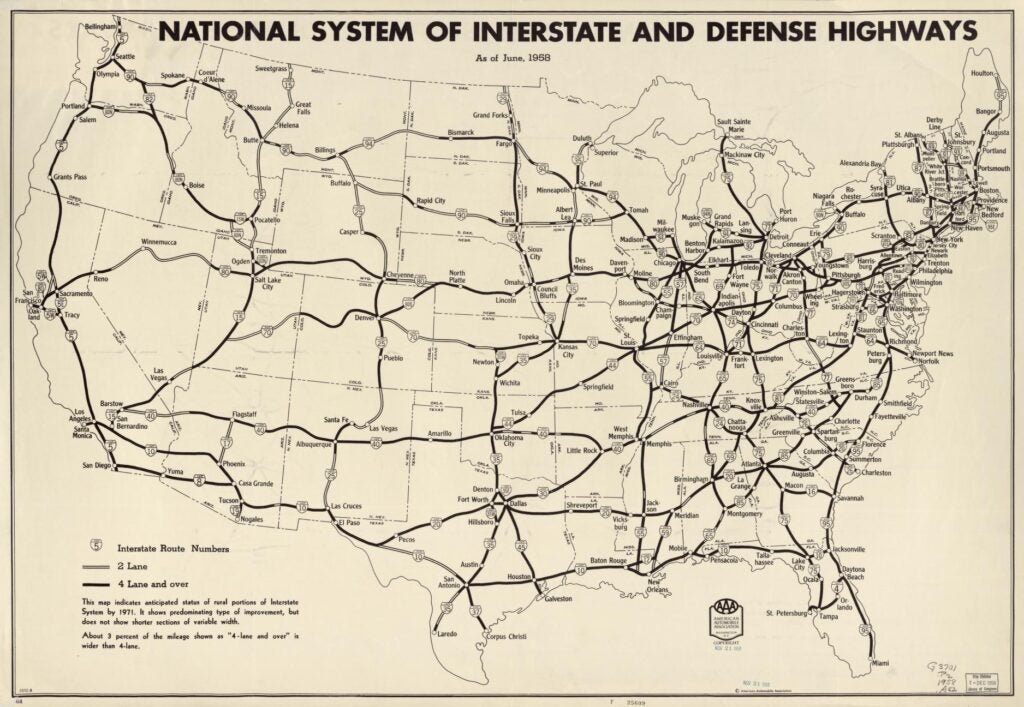

The only trouble was, these historic African American neighborhoods didn’t exist anymore. They had been destroyed to make way for the I-75.

The memory stuck with Carter, even as her professional career took her out of Detroit, first to the New England Conservatory and Oakland University in Rochester, Michigan and later to New York where she established herself as a top jazz violinist and recording artist. Then, in 2006, the Lincoln Center commissioned Carter to write a new piece of music. Searching around for a project, she found herself revisiting the disappearance of Black Bottom.

“I just found myself wanting to know more about it. I had heard so many stories growing up, and the neighborhoods were so different,” said Carter.

Carter worked with the poet Leslie Reese to create a musical tribute to Black Bottom, which premiered at the Lincoln Center in 2006. Reese’s poetic lines recalled the landscape while Carter’s violin invoked period music and improvised new themes. But the overall trajectory was loss, memorialized by Reese’s haunting “By the 1950s, Black Bottom was gone/Gone in a Phrase of Air/Just as if it had never been there.”

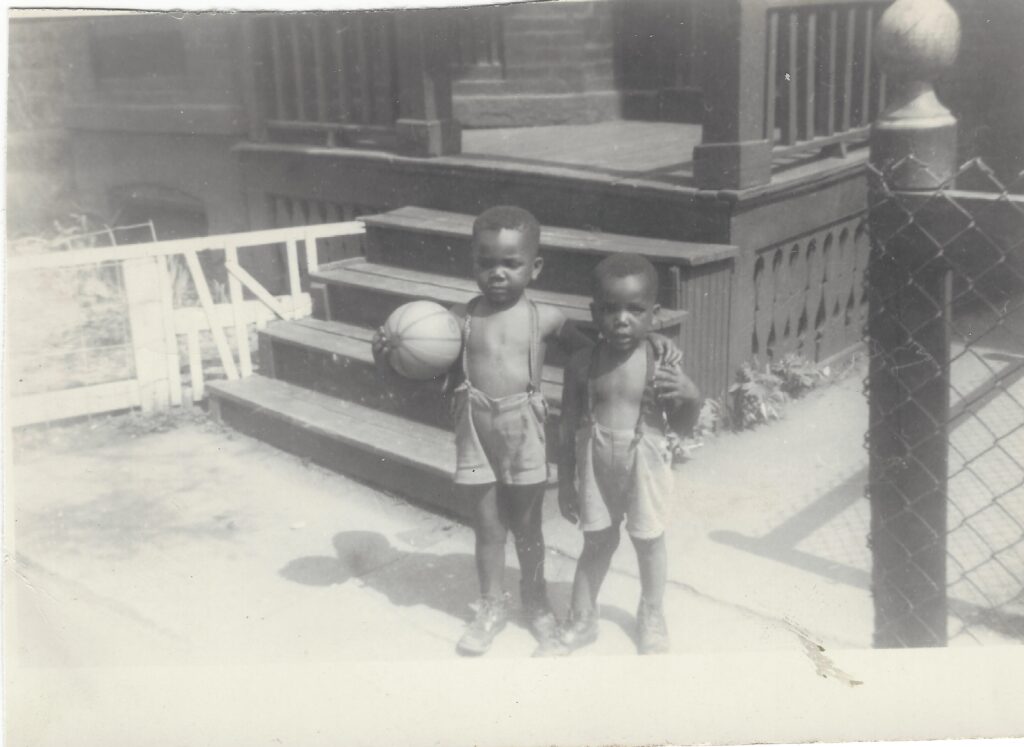

“Gone in a Phrase of Air”ultimately became the name of the project, although it sat on hold for a while. Carter won a MacArthur Fellowship (colloquially known as the “genius grant”) in 2007, and many projects occupied her time over the next decade and a half. But she found herself perpetually returning to family photographs and to her mother’s stories.

The stories sometimes surprised Carter.

“My mom would ask me, what tunes are you working on now? And I’d tell her she wouldn’t know them,” said Carter. Carter’s grandmother graduated from Morris Brown in 1915 with a bachelor’s in piano pedagogy, but Carter’s mother did not have an ear for music. As Carter said, she didn’t really believe her mother knew the jazz pieces she was playing. “And so I’d start playing a riff on my violin. I started playing “a tisket, a tasket” and my mom started to sing it. I was shocked! And she told me how she had heard Ella [Fitzgerald] sing live in Black Bottom.”

The jazz clubs of Black Bottom hosted many of the jazz greats of the 30s and 40s and was also one of the founding sites of bebop music. Barry Harris, the Detroit native and jazz pianist who later toured with Cannonball Adderley and collaborated with Coleman Hawkins, told stories to Carter about the great jazz pianists who came through town, performing at places like the Blue Bird Inn.

“He told me about how they would all gather afterwards for cutting sessions,” said Carter, referring to the famous late-night jazz sessions where players would play and improvise, often competitively. “That was how they learned from each other.”

Carter found herself doing more and more research, looking through historical sources like Green Books and city directories, collecting oral histories and looking through photographs.

As Carter took “Gone in a Phrase of Air” on tour, she discovered something else—many people reported the same stories in other cities. “In virtually every other urban city, there was this experience of Black and brown neighborhoods and immigrant neighborhoods being destroyed to put in highways,” said Carter. “The people forced out were not compensated. Whole neighborhoods were turned over.”

The creation of a federal interstate system in post-World War II America profoundly remade the landscape. Highways cut through working-class neighborhoods in cities and also provided the infrastructure (and opportunity) to concentrate housing in suburbs.

“My mom grew up very poor, but she never felt poor,” said Carter. “In those old neighborhoods, everyone lived together. You’d have a doctor living next to a cobbler, living next to factory workers.”

Carter’s project combines the historian’s task of recovering lost communities with the artist’s ambiguity of presentation. “Gone in the Phrase of Air” has come a long way since 2006. It now uses visual media as well as spoken word and engages more communities.

And it is just a beginning.

“I’ll be offering a class on ‘the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 and urban renewal’ at UCLA,” said Carter. She envisions it being a much larger multi-media project, one where collaborators can combine scholarship and art to recover lost communities. Such projects are not uncommon with faculty at The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music, where faculty like musician and composer Arturo O’Farrill has brought multi-faceted and interdisciplinary projects like Four Questions and Fandango at the Wall to students as well as to the wider world.

Carter’s plans are similar. “I’m hoping to get a grant so I can develop the project further. It’s going to need more research, more work. I’ve been performing it in performing arts centers, and I want to also take it to community centers. These things are still happening, neighborhoods are still being destroyed and people living through it don’t often see it happening right before their eyes.”

Carter hopes ultimately to take “Gone in a Phrase of Air” into elementary schools, so young students can be introduced to the history of neighborhood formation and do their own research. Coincidentally, that is where the project first took seed—in her mother’s car, driving to the elementary school where she taught kindergarten.

“I was a horrible student,” admitted Carter, laughing. “And now, here I am, doing all this research, and I can hear my mom saying, ‘I wish you had taken this much interest when you were in school.’”

See Regina Carter with Patrice Rushen in Dialogue and Performance, Monday, April 1, 3:00 p.m. at The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music. This event is free and open to the public. For information about this event, and to register via Eventbrite, click here.