By Jeremiah Lockwood, Research Fellow

Lowell Milken Center for Music of American Jewish Experience

In an apparently unproduced radio drama, the Malavsky Family present an allegory for the trials and successes of Jewish music in the American marketplace.

In 2020, the UCLA Ethnomusicology Archive received a gift of a unique and compelling article of material culture relating to cantorial music: the personal scrapbook kept by the Malavsky Family Choir. This wonderful artefact spans the career of Cantor Samuel Malavsky (1894-1983), a Russian-born cantorial star, and the choir composed of his six children. (For an introduction to the story of the Malavsky’s, please see my first blog post on this theme. Among the press clippings, advertisements and record catalogs, I found a surprising piece of creative writing: the script for the pilot of a radio script written in English called The Horowitz’s and unmistakably tailored as a star vehicle for the Malavsky’s. The script focuses on the relationship between an elder cantor and his young daughter, named Goldie, named for Goldie Malavsky, the eldest daughter and the lead soloist in the family cantorial choir. Apparently, the roles were created for Goldie and her father, perhaps even written by Goldie. The script is undated, but likely dates from around 1950 when the Malavsky Family Choir was beginning to perform and record prolifically.

Yiddish Radio played a prominent role in the life of Jewish immigrants, creating what cultural studies scholar Ari Kelman calls an “acoustic community,” that framed opportunities for Jews to hear their lives and aspirations reflected through mass media in their own language, Yiddish, and in cultural terms that were intimately familiar. [1] At the same time, radio opened up private life to the influences of marketing and popular art forms. As Jewish Studies scholar Jeffrey Shandler notes, “radio brought an important innovation to private life, reshaping domestic spaces by linking them with a vast, virtual public sphere.” [2] Radio played a role both in the maintenance of Jewish particularism, through language and musical genres specific to the community, and simultaneously acted as a mechanism of Americanization, through enculturation into American styles of consumerism and leisure activities. Jewish themed radio dramas on air such as The Goldbergs, which later became a popular television program, conveyed messages about the potentials for success in America narrativized through the story of an immigrant family’s economic and social mobility. [3]

Yiddish language radio was first heard in New York City in 1926 and reached a peak listenership of 1.75 million people in the years after World War Two. [4] From the 1930s onward, Jewish themed radio was increasingly produced in English or in bilingual presentations that moved between Yiddish and English. Throughout the lifetime of Jewish radio, cantorial music played a prominent role. Numerous star cantors had radio programs, supplementing their synagogue prayer leading schedules with mass mediated versions of sacred music. Radio was an important outlet for women performers of cantorial music who were generally forbidden from performing in synagogues.

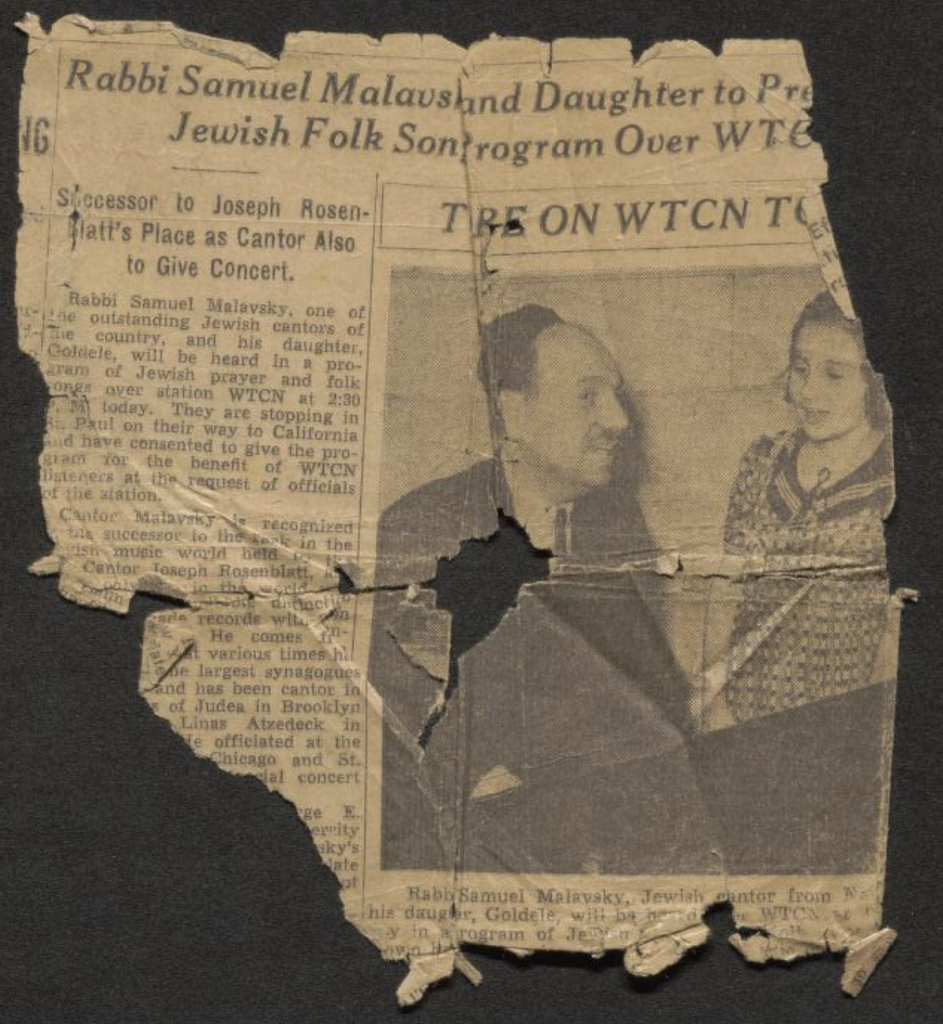

Yiddish and Jewish-themed radio was by no means confined to New York. Contrary to pervasive narratives of language decline in the assimilated American Jewish community, in the decade after World War Two the number of stations broadcasting in Yiddish actually expanded. Radio stations hailed new communities in their mother tongue as Jews moved away from the East Coast into the Western States. One of the two copies of The Horowitz’s script included in the Malavsky scrapbook is typed on the stationery of the Mid-West Broadcasting Company, Inc. Perhaps this company was associated with WTCN, the St. Paul radio station that the scrap book shows as an early performance venue for Goldie Malavsky, featured as a child soloist with her father.

The Horowitz’s opens on “Cantor Horowitz” tutoring his daughter “Goldie” in the appropriate performance style for a song referred to as “Ai-li-lu-li-lu.” All of the elements here are closely modeled on the Malavsky family. Cantor Horowitz, like Samuel Malavsky, is an immigrant cantor with a heavy Yiddish accent. His daughter is an American born girl with a talent for singing “old world” melodies. The song itself refers to the piece originally recorded by Yossele Rosenblatt, Samuel’s mentor, that became a standard in the repertoire of the Malavsky sisters, Gittele and Goldie, and was featured on their 1958 Tikvah Records release “Yiddish Songs” under the title “Mother’s Lullaby.”

The conceit of the radio play, and its source of maudlin sentimentality, is that the cantor has fallen on hard times after the death of his wife and has turned to drink. He has come to the point where his ability to take care of his daughter has come into question. Their domestic music making scene is interrupted by a visit from a woman from the “Children’s Protective Society.” The social worker has come armed with a court order to take Goldie away from her father whose competence has come under question. The immigrant cantor bemoans that despite all his promise and talent, he has been undone by bad luck and the sad fact that there is “no room for ‘Chazanish’” in America.

The scene then moves to the courthouse. Here the father and daughter are, improbably, given the opportunity to burst into song to prove to the court that they are indeed talented singers. The father sings “Ki Lekach Tov,” a signature piece of many cantors drawn from the Sabbath morning Torah service. And Goldie sings “Longing for Home.” This English title probably refers to “Ich Benk Aheym,” a piece from Joseph Rumshinsky’s 1919 Yiddish operetta Dem Rebns Nign. Goldie Malavsky’s unique re-interpretation of “Ich Benk Aheym,” an almost complete revision of the original Rumshinsky aria, heard on her only solo record from the late 1950s, is one of the great classics of mid-century Jewish American music.

The story comes to an abrupt happy ending when “S.A. Perkins, of the Radio Broadcasting System” offers the father and daughter duo a contract to sing on the radio and confirms he is “willing to pay them a fair wage.” Somehow, without mention, the charge of drunkenness has been replaced with a more manageable question of adequate livelihood to sustain their household. The stringent, abrasive care of the intrusive social worker has been replaced by the more oafish and lenient justice of the free market. With his ability to support his daughter suddenly confirmed, Goldie is returned to her father. The Judge wishes the Horowitz’s success in their new career as radio artists, the radio announcer suggests that the listener tune in next time to hear the further adventures of “a vagabond singer and his little daughter,” and all is right in their world.

The Horowitz’s radio play offers a somewhat clumsy and childish allegory that manages to touch upon some of the cultural problems the Malavsky’s encountered in their music career. The first issue we encounter is the question of how to educate young people in the aural culture of Jewishness in the new American context. While Samuel Malavsky received his training by working as a child in cantorial choirs in which he was forced to perform to earn his livelihood, the only force compelling his daughter to work on her music is parental authority and her own interest in music. In the radio script, the father emphasizes the role of labor in making music. He recalls, “when I was a little boy of your age, and when I first sang as a ‘meshorer’ [Yiddish, cantorial choir singer] with Chazan Goechmann in Kiev, how he used to make me work. Hour after hour, he would make me sing over and over until it was letter perfect. There couldn’t be a single error in it.” He admonishes his daughter for not working hard enough, presumably in comparison to the adult labor he performed as a little boy. Tellingly, the scene of the father’s attempt to enculturate his daughter into the musical values of the Jews of the Pale of Settlement is interrupted by the authority of the American government.

While both father and daughter are horrified at the idea of being separated, little Goldie is entranced by the social worker’s “pretty golden hair.” The forces that separate the immigrant generation from their children is personified in the radio script by a force that was benevolent, seemingly all-knowing, and able to collect information about the most intimate aspects of life by means of an observation network powered by neighbors and local shopkeepers. The interaction with the social worker creates the impression that the authority of the state is enforced through “soft” power, through a network of cultural expectations that were not explicitly stated but rather were distributed across the social worlds of Jewish immigrants and that their children were especially susceptible to.

Although the father’s out of date music is ostensibly the problem driving the family apart, their music is also the force that will offer them a second chance at remaining united, across the problematic issues of economic vicissitudes and generational difference. The ear of a non-Jewish radio man, who, deus ex machina, just happened to be present in the courtroom, was piqued by the father and daughter’s sound. In the logic of the play, he believes that there is money in the sound of their voices. Their impromptu audition, focused on Hebrew prayers and Yiddish songs, indicates that their special access to tradition is what can offer them legibility as artists. In this melodrama about Jewish music, the mediascape of the radio offers the family new opportunities to perform and to present their special forms of insider knowledge. The same musical offering that was rejected as “old fashioned” in the synagogue, was now to be a path towards success, through the mechanism of new mediated technologies that could reach mass audiences. In the logic of this radio play, the medium is more important, perhaps, than the musical style of the message being conveyed.

Unlike The Goldbergs, whose adventures involved more or less consistent forward movement and economic growth, The Horowitz’s were introduced as outcasts to American society. Through the media of radio, the family’s obscurity and degradation were about to be transformed, rendering the non-conformist outsider into a heroic artist. This passageway to success offered by the new technologically mediated community of the media is a stylized representation of the career path of the real life Malavsky family. Leaving the synagogue as a site of cantorial performance, Samuel Malavsky took a risk embracing a path as a stage and radio personality. Like some of his Jewish music peers from Russia who were trained as meshoyrerim but who made their livelihood in Yiddish Theater, Samuel Malavsky stepped out of the synagogue and into the new world of media — and took his brilliantly talented daughter Goldie with him. In this way he was able to find a niche for himself and his family that offered new opportunities to perform their sacred music, unmoored from the institutions of Jewish American life with their oppressive and self-defeating rules relating to gender and decorum.

In the fantasy of The Horowitz’s radio play, and in the real life of the Malavsky Family, radio created an opportunity for success. As stars of radio, the Malavsky’s were able to defy conservative social conventions and present their unique family music style. They achieved this success in part by embracing an exuberant, pathos-rich and unabashedly stereotypical representation of Jewish sound that translated brilliantly into the new media of Jewish radio. The capitalist mechanism of commercial radio supported “ethnic” music projects that could project an image of a unified community, which could then be harnessed to generate advertising revenue marketed to niche segments of the population. The Malavsky’s eagerly played the role of representing Jewishness to the Jews, perhaps recognizing the parallels between the mediascape and the synagogue. In both contexts, radio and pulpit, cantors were given a “stage” from which to present the voice of the people and to be heard and loved as a singular artistic personality whose art spoke to and for the listener. Ironically, in the American context in which the Malavsky’s worked it was the radio, and not the synagogue, that became the key arena in which to promote and extend their Jewish sacred music.

Unfortunately, the Malavsky radio broadcasts, like The Horowitz’s, were mostly ephemeral, unrecorded and lost to time. The Malavsky signature style, however, continues to resonate in corners of the Jewish music world. Based in the ebullient and playful meshoyrer sound that is emblematic of Russian Jewish cantorial culture, the Malavsky Family sound has mostly disappeared from the American synagogue but many of their signature pieces remain familiar through their classic mid-20th century records.

NOTES

[1] See Ari Kelman, Station Identification: A Cultural History of Yiddish Radio in the United States (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009).

[2] Jeffrey Shandler and J. Hoberman eds., Entertaining America: Jews, Movies, and Broadcasting (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003), 101.

[3] See Donald Weber, “Goldberg Variations: The Achievements of Gertrude Berg,” in Shandler and Hoberman eds., Entertaining America, 113-123. [4] Kelman, Station Identification, 214.