John Baily Presentation Abstract: The Afghan rubâb at the Indo-Persian music interface

The Afghan rubâb is from a widespread family of double-chambered plucked lutes found in Central Asia, the Middle East and the Indian Subcontinent, such as the Pamir rubâb, the Dulan rubâb, the Kashgar rewap, the Tibetan dramyen, and the Sherpa tungna. Alyn Miner’s admirable monograph Sitar and Sarod in the 18th and 19th Centuries mentions three types of rubâb found in Hindustan in that period: the Persian rubâb, the dhrupad rubâb and the Afghan rubâb. The Afghan rubâb as we know it today has three sets of strings; namely, three melody strings, three long drones and up to 15 sympathetic strings, the shortest of which also serves as a high drone. The instrument usually has four frets, giving a 12-note approximately equidistant tonal system. How the rubâb acquired its sympathetic strings and fretting is a matter of conjecture.

Pashto speaking Afghans (generally known as Rohillas) migrated to India over the course of many centuries, settling largely in an area between Delhi and Lucknow which came to be called Rohilkhand; its major city Rampur. Many Rohillas were professional mercenary troops, especially cavalrymen, who served the Mughals and other local rulers. They were also deeply involved in the import of horses, an important military asset, from Central Asia to the Subcontinent, thereby creating a trade route which might be termed the “Equine Road”, although many other goods besides horses passed along it. The Rohillas used the Persian rubâb as a military instrument, leading their mounted troops into battle. The so-called “Indo-Afghan Empire” was at its peak from 1710 to 1780.

It is my conjecture that it was in Rohilkhand that the Afghan rubâb emerged, with sympathetic strings adopted from the recently invented sârangi. Frets were added to make it easier to play. Seeking a musical style beyond Pashtun regional music, Rohilla musicians learned a simplified version of Indian music from dhrupad rubâb players and started to assemble a classical repertoire suited to their new instrument. The redesigned Afghan rubâb, with its newly acquired classical repertoire, then travelled up the Equine Road to Afghanistan and beyond, perhaps in the early 19th Century.

In the 1860s the Amir of Afghanistan, Sher Ali Khan, invited a number of nautch groups to Kabul to serve as court entertainers and music teachers for the aristocracy. Sher Ali Khan was followed by a succession of music-loving rulers of Afghanistan, notably Amanullah and his officially appointed Court Singer, Ustad Qassem. This was the time when the Hindustani ghazal, often with rubâb accompaniment, became the principal genre of vocal art music in Kabul, with texts drawn from the great traditions of Persian and Pashtun poetry, and a musical style rooted in that of Hindustan.

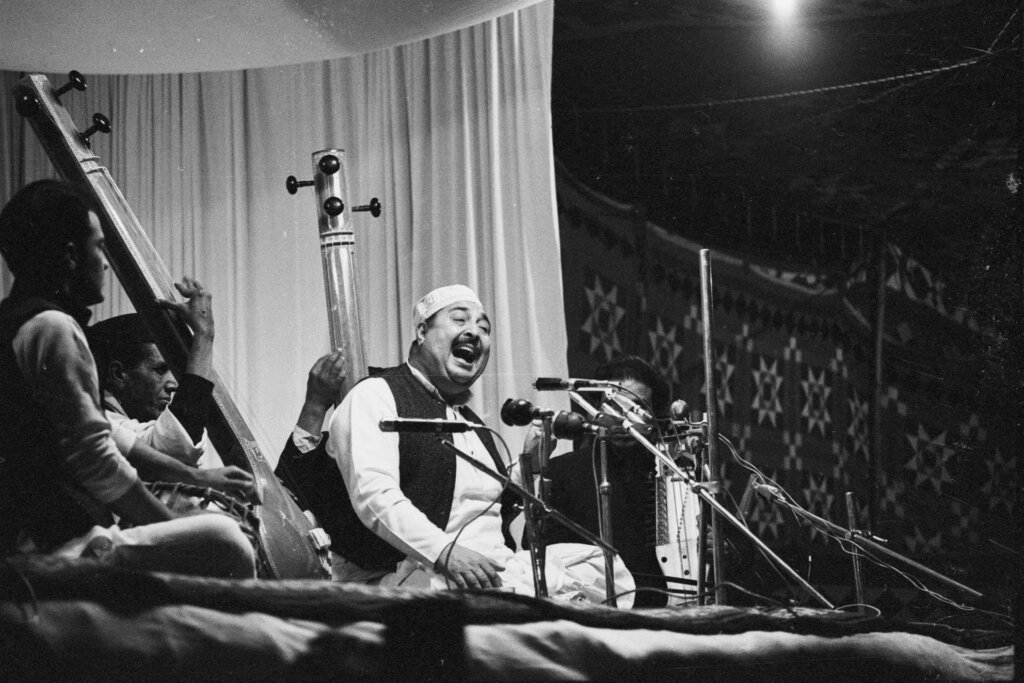

In the first part of the 20th Century the urban music of Herat, close to the border with Iran, was very much in the Persian style, with classical poetry sung to the accompaniment of the târ and santur. In those days the Afghan rubâb was little known in Herat. The new music from Kabul reached the city in the 1930s, when the eminent Kabuli singer and multi-instrumentalist Ustad Nabi Gol resided there for three lengthy periods under the patronage of a newly-appointed Governor from Kabul, eager to introduce the Heratis to the new music from the capital. On his first two visits Ustad Nabi Gol brought accompanists from Kabul but he also trained two young Herati musicians in the new style of music, Amir Jan Khushnawaz learned the vocal style of Kabul and played rubâb, while his brother Chacheh Ghulam played tabla. On his third visit Ghulam Nabi brought no accompanists, telling his students they were now qualified to play with him. In due course Amir Jan became the leading singer of the Kabul style in Herat and one of my main sources for classical compositions for the rubâb.

There are important differences between Afghan and Hindustani renditions of rag-based classical instrumental music. On a number of counts Afghan practice sounds and looks like a simplified version of Hindustani practice. It is reported that Ustad Sarahang, Afghanistan’s great singer, for many years the student of Ustad Ashiq Ali Khan in India, allegedly declared that everything done in the name of classical music in Afghanistan was wrong!

Photo credit: Liliane de Toledo, Geneva

Link to Calendar Page

Link to Calendar Page