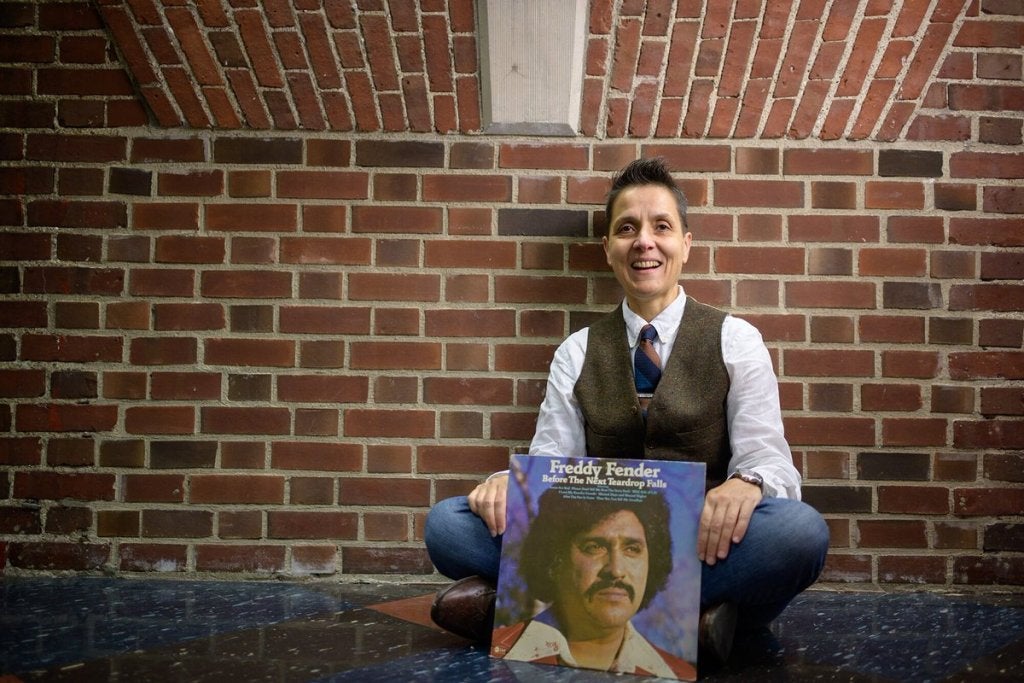

On Tuesday, October 18 at 3:30 p.m., Nadine Hubbs will deliver the Robert M. Stevenson Lecture in Lani Hall at The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music. Her talk, “Country-Loving Mexican Americans: Inevitable Fandom and Dual Patriotism among Mexican American Country Music Lovers,” will present her most recent fieldwork and research.

“There’s a notion I’ve encountered in the north,” explained Hubbs, “that country music is exclusionary, that it’s white music and would not appeal to Mexican Americans or offer them a space of belonging. But that’s not what I’ve found in my research.”

Hubbs has conducted fieldwork in northern and southern California and in Texas, all borderland communities with deep, complex histories of interactions between people of Anglo, Indigenous, and Mexican roots. Much of the West’s distinctive culture—cowboys, rodeos, rugged individualism—comes right out of this interaction. The vaquero (cowboy) is a figure of Mexican origins. Western aesthetics, from music to clothing to jewelry, is largely Mexican and Indigenous in its roots.

Country music, by contrast, has long been cast as white music—white in origin and appealing only to white people, especially those of the working class.

This is precisely the myth that Hubbs explodes in her new work.

“I’ve talked with Mexican American fans who love country music,” said Hubbs. Contrary to any notion that popular music might serve to Americanize Mexican Americans, she found just the opposite. “The Mexican Americans I spoke with made a strong case that country music belonged to them, that it was Mexican American music. They also spoke of country’s patriotic songs, not as alienating or excluding them, but as reminding them of their appreciation for the sacrifices their families made to give them a life in the U.S.—and at the same time of their love and gratitude for their Mexican culture and identity.”

Exploding myths has become a hallmark of Hubbs’s career. Her first book, The Queer Composition of America’s Sound (2004), is a cultural history that constellates a circle of important mid-twentieth-century American composers including Leonard Bernstein, Virgil Thompson, Aaron Copland, and others. At the heart of the book lies an intrigue: how did a group of gay composers create a long-awaited “American sound” in U.S. concert music during the most homophobic period in the nation’s history?

Her answer highlights homophobia.

“Social, legal, and other oppressions caused queer people to band closely together,” explained Hubbs. “In the case of these composers it led to the creation of powerful networks of mentoring, support, and artistic influence. In this way, homophobia helped to propel these gay composers to the highest ranks of American music.” The book received strong praise in scholarly reviews and was written up in The New York Times and Los Angeles Times.

The book is dedicated to the late Philip Brett, a distinguished professor of musicology at UCLA at the time of his death, twenty years ago this month. Brett was a friend and mentor to Hubbs and many other sexuality and gender scholars in music, and a founder of LGBTQ+ musicology.

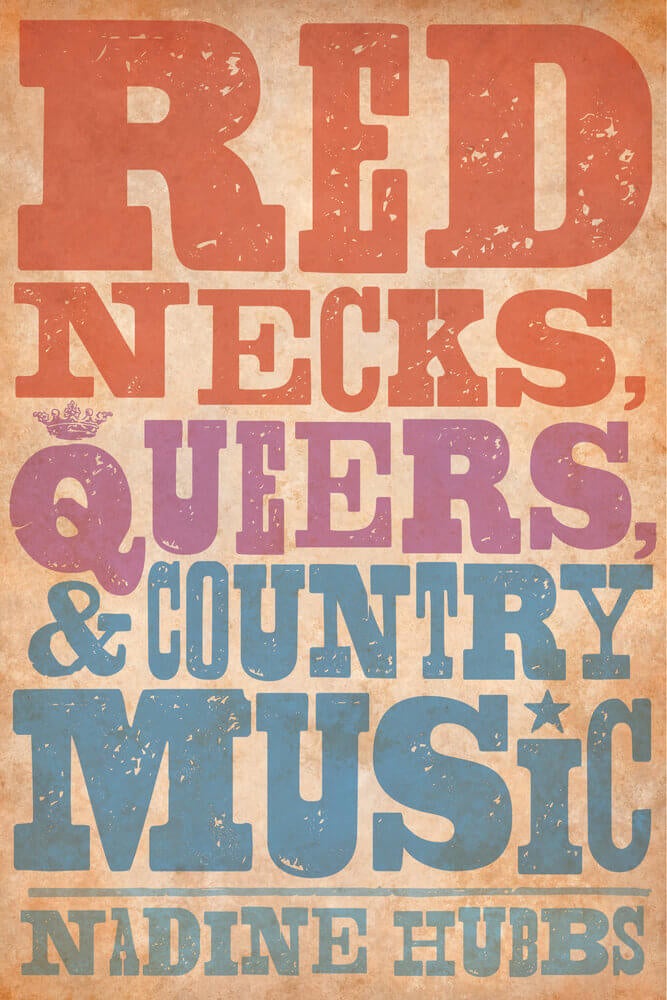

With her second book Hubbs moved from urbanite, cosmopolitan composers to Rednecks, Queers, and Country Music (2014). Hubbs examined the intersection of sexuality, aesthetics, and social class to show how, and why, middle-class Americans simultaneously claim eclectic musical tastes and invoke the mantra “I’ll listen to anything but country,” thereby excluding music associated with working-class whites.

Was it a big leap from Copland to country?

“I surprised myself by coming around to country music,” said Nadine Hubbs of her second book. Her scholarly training was in classical music theory and her dissertation and first publications in musical organicism. Her connections to country music, meanwhile, were more personal. “I grew up in a blue-collar family outside Toledo. My dad drove a freight train. My aunt and uncle owned a beer joint in the cornfields. And their jukebox was filled with great golden-age country records: Hank Williams, Tammy Wynette, George Jones, Charley Pride.”

Her motivation for turning to country music was to illuminate issues of social class and, again, the history and politics of sexuality. Her working-class roots and early exposure to country music made it a natural fit.

Except there was one problem.

“There was no established literature on class in my field,” said Hubbs. It took her years just to build a bibliography. “Much of my class literature came from sociology and cultural anthropology. Sherry Ortner, a UCLA Anthropologist, was an important influence on my work.” The result was a book thatsheds light on the role of musical taste in producing classinequality in America and uses country music as a lens onto the middle-class monopoly on sexual-gender acceptance and on social progressivism more broadly.

For Hubbs, it made sense to continue her work with country music, now to investigate its connections to Mexican Americans. Since there was little information about Mexican Americans and country music, she generated new data through field work.

“The Mexican American country fans I spoke with emphasized the importance of the Mexican figure of the cowboy in country music and the influence of rancho culture. They cited the Mexican origins of the American Southwest, a vital country music zone. Contrary to any notion that they were excluded by country’s patriotic songs, these fans expressed deep, bicultural appreciation for them.” And contrary to the myth that country music exclusively speaks and belongs to white listeners, Hubbs reports: “My interlocutors pointed to all these connections and to what they called country’s ‘Mexican values’ as proof that country music belongs to Mexican Americans.”

So much for the myth.

Nadine Hubbs will deliver the Robert M. Stevenson lecture in Lani Hall on Tuesday, October 18, 3:30 p.m. The talk is free and open to the public. Find information about parking and the event space here.