Forty years after the African music festival Freedom Melody challenged apartheid, an artist brings the songs of resistance and humanity to the stage

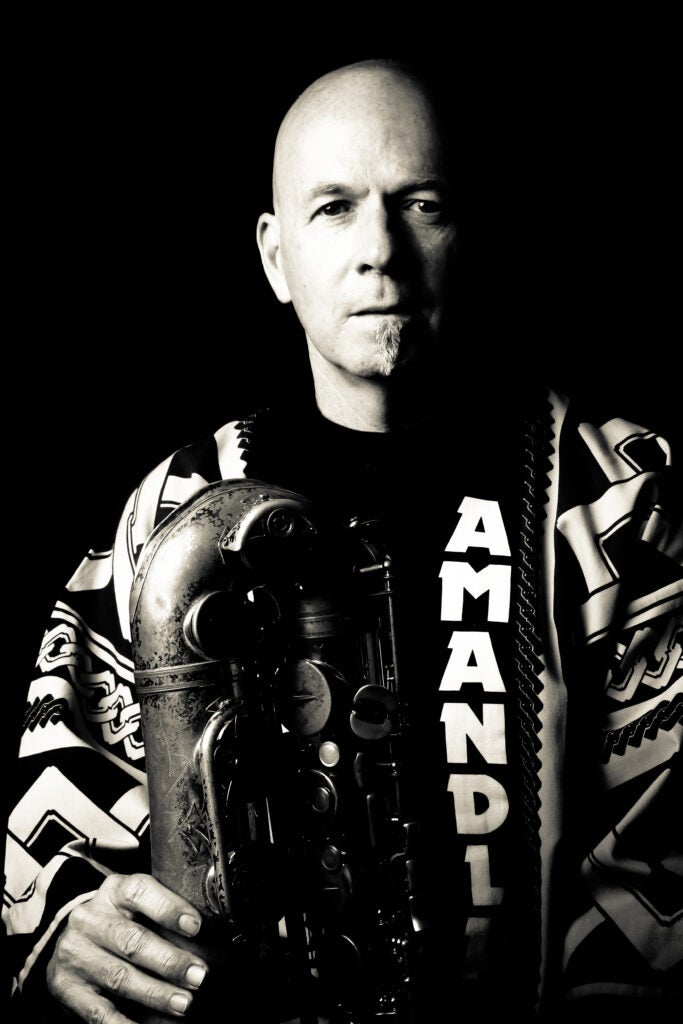

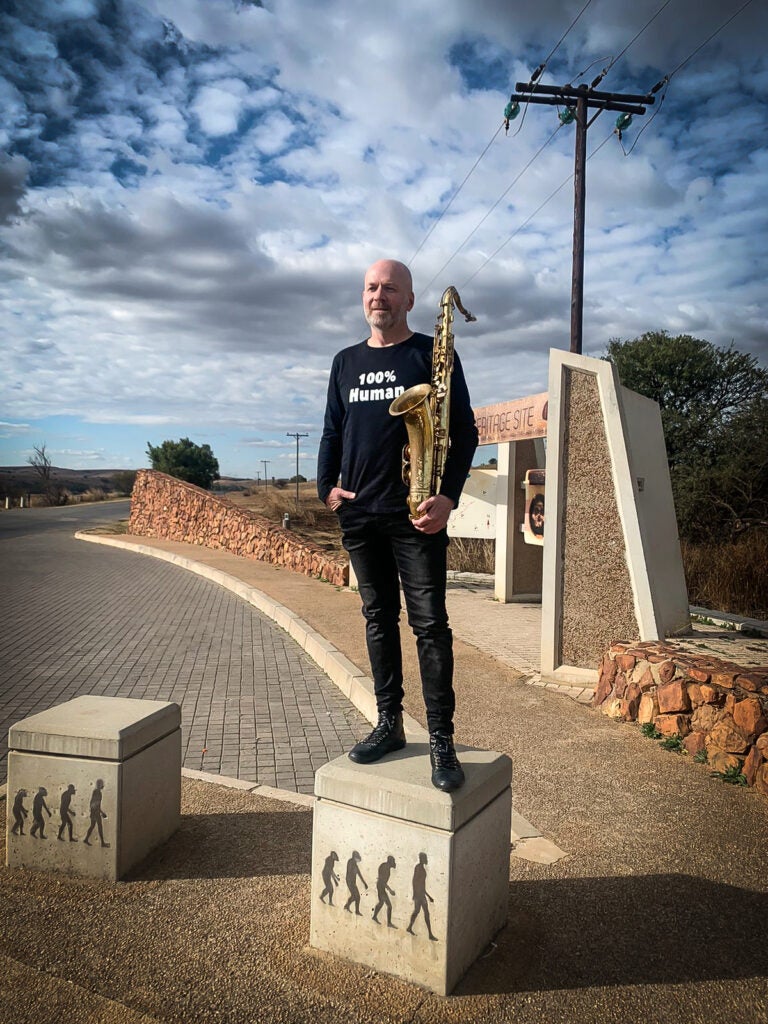

On Wednesday, October 29, The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music presents the West Coast premiere of Freedom Melody, 2025 in concert, a powerful new work by South African jazz musician and composer Steve Dyer. Fresh from its North American premiere at the Lincoln Center in New York on Saturday, October 25, this new project commemorates the 1985 Freedom Melody festival that drew musicians from across southern Africa—as well as from other continents—in an act of resistance against the apartheid government of South Africa.

Dyer, just having completing his musical studies at the University of Natal, was at the 1985 festival that drew jazz musicians of astonishing ability, among them pianist Abdullah Ibrahim, trumpeter Hugh Masekela and trombonist Jonas Gwangwa. The festival drew international acclaim. It also triggered a violent response from the South African Defense Force (SADF), which launched its infamous raid on Gaborone on June 14, 1985.

Forty years later, Steve Dyer reimagines the spirit and defiance of Freedom Melody, reflecting on how South Africa—and the world—have changed. In a frank interview, Dyer opened up about life in exile in the 1980s and his hopes for Freedom Melody in 2025.

# # #

Why commemorate the Freedom Melody festival now?

That festival happened at a time when we fought for the highest ideals of humanity in the face of extreme oppression. Even staging a music festival at that time put the organizers at great personal risk. We had dreams, and we achieved great things. Forty years later, those dreams haven’t turned into reality. So we also have to face up to the shortcomings. But that doesn’t take away from the achievement.

You attended the Freedom Melody festival in 1985, right?

Yes, I was living in in Gaborone [Batswana] at the time and I helped organize it.

You grew up in South Africa, so how did you come to live in Botswana?

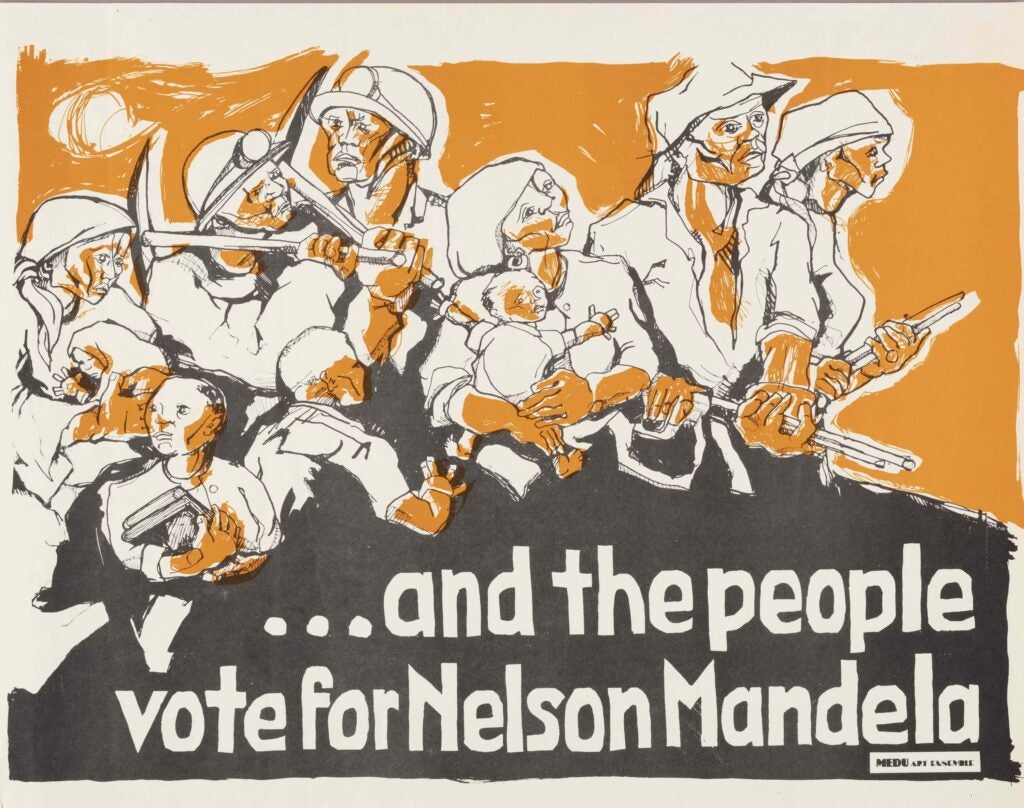

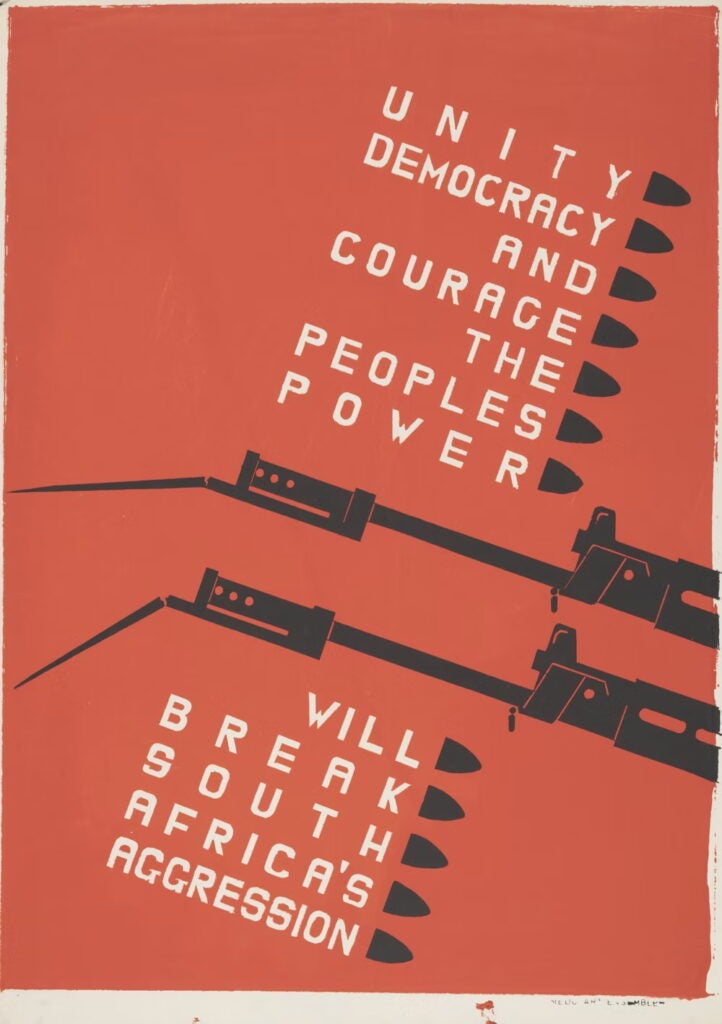

In South Africa at the time, all white men like me were compelled to go into the Army. When I left university, I wasn’t willing to wear the uniform. I don’t think I ever considered it. And so I skipped the country and went to Botswana. It was there where I met Jonas Gwangwa, a sensational South African trombonist, who had been living in exile for decades. There was a cultural collective in Gaborone called the Medu Art Ensemble and I became involved with them. They had a graphics unit that made a lot of posters that became quite iconic in the struggle against apartheid.

They had a music unit, and at the time, Jonas Gwangwa was spending about half of his time in Botswana and half his time with the Amandla Cultural Ensemble of the ANC [African National Congress].

The ANC was the political party that spoke for the rights of Black Africans in South Africa, although it was exiled from 1960-1990—how was the Amandla Cultural Ensemble involved?

The political leadership of the ANC recognized the importance of culture within the freedom struggle. These were the people who would go around the world and spread the word. And so they formed the Amandla Cultural Ensemble. Many of the members came from … Well, all the members were trained militarily. In the camps in Angola, they used to have a jazz hour where people would come and play, recite poetry, and perform. So, they formed this ensemble, and Gwangwa took them around the world to perform.

Jonas Gwangwa was a mentor and a father figure to me. I met him when I arrived in Botswana in 1982 and they put on a festival that year. Musicians came from all over, musicians who had left South Africa for Europe or the U.S. And it was a highly developed music festival with a strong engagement of the concept of Black Consciousness, and there were big contestation of ideas between the ANC and the PNC (Pan-African National Congress).

And all this you saw at a musical festival?

That period of my life in Botswana grounded me, as a person and as a musician. Music, I realized, has a story to tell. It is more than just playing the notes. Music has social meaning; it has a place in society. And in these cultural spaces, there was debate and discussion, and very powerful ideas about humanity, about right and wrong.

But, I have to be clear, it had already been instilled in me. Growing up, my mother was my moral compass. I feel a great deal of gratitude toward her. She was a member of the Liberal Party and a member of Black Sash [an anti-apartheid, non-violent resistance organization in South Africa]. My opposition to apartheid formed in me when I was very young because she showed me that life was not what it should be under that government. And what I was seeing in Botswana just grounded me.

Did Freedom Melody 1985 aim to achieve the same thing?

We all had the same goal. We wanted to overthrow apartheid. But that’s a complicated goal, and we had many stories to tell. The festival took place in multiple places and over several days. It was amazing the number of musicians who traveled to attend that festival. Bheki Mseleku [another South African musician living in exile in London] traveled to Botswana to attend that festival. It was like honeybees attracted to the flowers. Just amazing.

How did it feel performing?

It was powerful. But it was hard, too. When I played, I didn’t know whether I’d be allowed back into South Africa, ever in my life. This was five years before Mandela was released, but no one had a clue that it would happen.

We were all living in a low-intensity war zone. South Africa had agents crossing the border. People would come and take part in the cultural activities, or photographers would go to work with the ANC, and many of them were informers [for the South African government]. You had to be very careful who you chose to talk to, how you talked to them.

Sometimes after a gig, someone I just met would offer to give me a ride home. And I’d say okay. And when we’d get to the street corner, I’d say “I’ll be fine from here.” I didn’t want to tell them where I lived. There was a whole subtext of violence. Some of the militants would come through in transit, trying to get back into South Africa to do whatever [military] operation.

That sounds frightening.

It is very scary to live in a society like that. But, because you were scared, you could party hard, too.

After the Freedom Melody 1985 festival, the SADF crossed the border and raided Garobone. Jonas Gwangwa was reputedly one of the targets.

The SADF killed 12 people. Some were activists. Others were just innocent people, caught in the crossfire. But the way they conducted the raid was … it was designed to terrify people, not just to kill people. They used a whole lot of bullets and machine guns. There was a fantastic artist who was part of the Medu Art Ensemble, and they killed him. But it wasn’t good enough for them to just kill him. They also shot up his paintings. They wanted to send a message.

You were a young man, and this must have generated a lot of emotions in you—fear and anger. Did you channel those feelings into your music?

Not anger, no. There was pain but not anger. Jonas Gwangwa told me a good story. He spent a lot of time in the U.S., and people would turn to him and say, “Hey man, you say you’re struggling, man, but your music sounds so happy.” And he would say “yes, it might sound happy, but if you listen carefully, there’s always a cry.”

So, there’s militancy, but not anger. Because, if you want to fight for something, anger makes you lose focus. You lose the objective.

How does your new project, Freedom Melody, commemorate the original festival?

Well, at the time of Freedom Melody in 1985, we had a specific goal in mind. We were trying to overthrow an unjust system. Now my thinking and my motivation are a lot more globally inclined. I’m not so centered on what’s wrong with South Africa. I’m interested more in what’s wrong with the world.

What do you see as one of the biggest problems we face today?

We are disconnected from one another. You know, the [1985 Freedom Melody] festival taught me so much about the African concept of Ubuntu. And I did an album called Ubuntu Music [2012] and I explained it as listening to other voices as well as your own and recognizing that each shaped the other. There are these concepts in indigenous African languages that convey that a person is a person by, through and because of other people. What that means is that, when I talk to you and you talk to me, you are shaping me and I’m shaping you.

There is a very sophisticated way of interaction in Zulu culture. When I greet you, I will say “Sawubona” which means “we see you.” We see you. I would say “we” even though I’m one person. It’s a very community-based perspective. It is very powerful. It is a recognition that, once we have had a conversation, I won’t be the same person afterwards, and neither will you.

You see this missing from our modern world?

When I walk past someone in the street here, I greet them, and you can sense that people are saying “what’s wrong with this guy?” It’s like people don’t see each other anymore. Like we don’t recognize one another. But that recognition, that is fundamental to what humans need. We need to recognize each other; not just our little nuclear families—you know: I love my wife, I love my kids—we need to see the expanded circle. We are all part of this expanded circle of life and love.

When you write music like Freedom Melody, how do you address these themes? How are they woven into your work?

At the bottom, at the heart of things, I’m a musician. When I write music, I don’t consciously say “I’ve got to make this piece called Freedom Melody, and it’s got to involve this and this.” I think that true art, it comes to you. It’s subliminal. It’s not a conscious thing. It’s about what you’ve lived through. It makes the most sense to say that I wanted a shape and a texture that recalled the history of the festival but also connects with 2025.

What do you hope people will take away from the concert?

I’m shaping you and you are shaping me. We are all connected. Let us all see each other again. The concept of Ubuntu is a way forward. It’s a different way of communicating. I want people to think about what is wrong in the world and how, through culture, through Ubuntu, find a new way of seeing each other. And it can be little things, like how we greet people in the street. It doesn’t have to be everything. I’m intent on bringing these ideas to people in a creative way.