By Jeremiah Lockwood, Research Fellow

Lowell Milken Center for Music of American Jewish Experience

Next in our ‘Treasures From the Oral History Project of American Jewish Music’ series, we see how for some cantors in mid-century Los Angeles, seeking labor rights for synagogue clergy went hand in hand with broader social justice issues of the day.

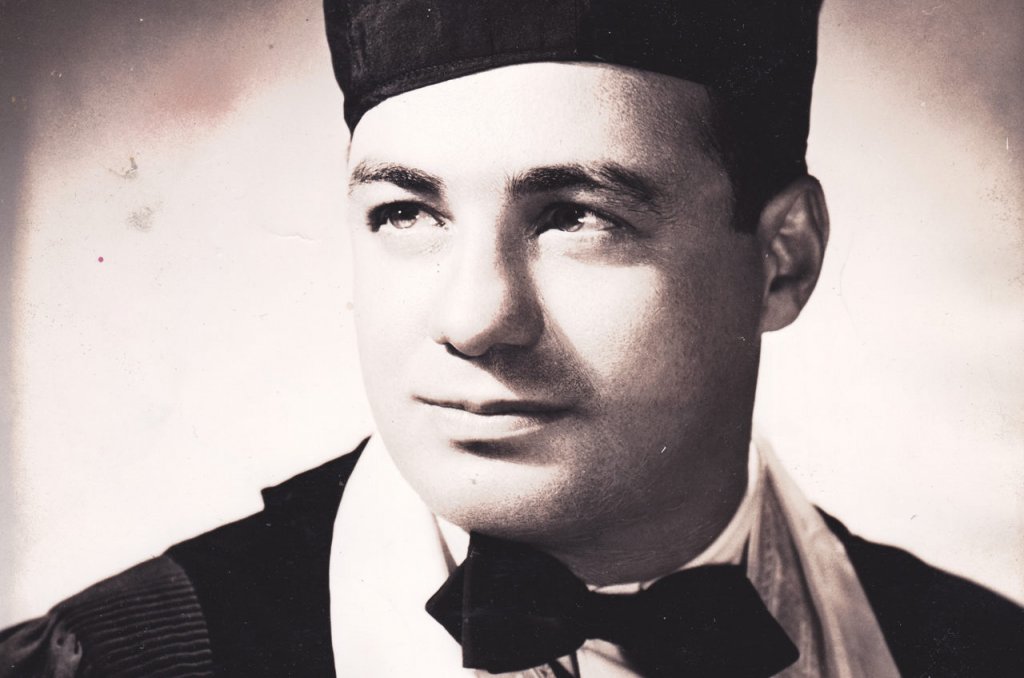

In honor of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, celebrated this week, and in memory of my friend Cantor Julius Blackman (1913-2018), who died three years ago at the blessed age of 105, this week’s edition of Conversations will focus on one small moment in the Civil Rights Era that showcases the commitment of cantors in the Los Angeles Jewish community to civil rights for African Americans. As I will suggest in the brief space of this blog post, the post-war movement of cantors to achieve labor rights for their professional organization was part of a broader concern with justice movements in the United States. For Cantor Blackman and his cantorial colleagues in Los Angeles in the 1950s, expanding the profile of cantors as representatives of the community and as professional artists went hand in hand with a political engagement and activist orientation he maintained throughout his lifetime. The confluence of the cantorial labor movement with an activist orientation that embraced the Civil Rights movement is at play in an important concert Blackman produced in 1953 that united the music of Italian Jewish refugee composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco with the performance of African American soprano Georgia Ann Lester. In a detailed interview with musicologist Neil Levin that was just made public on the Milken Archive Oral History Project, Blackman discusses the exploratory period in his life when he worked as a cantor and Jewish community organizer in Los Angeles. The broadly ranging discussion between Blackman, Levin and Cantor Nathan Katzman captured in this video provides a glimpse into the musical life of cantors in mid-century Los Angeles, including a few suggestive details about the role of cantors in forging bonds between Jewish and Black artists and their support for the Civil Rights movement.

I wrote about Cantor Blackman in an article published in 2019 that focused on the cantorial lessons I took with him and that located his pedagogic style in a tradition that was an important part of cantorial culture in the early 20th century. These lessons focused on the performance of nusakh hatefillah (Hebrew, the manner of prayer, used by cantors to designate the prayer melodies and motifs used in the recitation of the prayer services). Our lessons were perhaps more reflective of my interests in “golden age” cantorial music than Cantor Blackman’s musical priorities. Having lived a long life in Jewish music he was happy to spend some hours with me reminiscing about his years as a cantorial choir boy singing with star cantors of the 1920s and 30s like Yossele Rosenblatt and Pierre Pinchik, and especially his beloved mentor Josef Roman Cykowsky.

The focus of Cantor Blackman’s career, however, was not the preservation of heritage synagogue music, but rather in labor organizing, community building, and efforts to raise the status of the cantorate, especially through the commissioning of new repertoires in prestigious modern classical music styles. In his early years in Chicago, where he was born, Cantor Blackman had worked as a labor union organizer. After relocating to California in the 1940s, Blackman brought his political skills with him, serving as the founding president of the South West California branch of the Cantors Assembly, the union of cantors associated with the Conservative movement.

Alongside his work advocating for standardizing the remuneration of the labor of cantors, Blackman was also involved in initiatives that he saw as raising the prestige and aesthetic cache of the Los Angeles cantorial community. One major initiative he spearheaded was forming the Jewish Music Council, initially founded as an advisory board to the University of Judaism to raise musical education standards. At Blackman’s instigation, the Jewish Music Council expanded its footprint, inducting members from the broader pool of talent in Hollywood to create a musical community in which cantors were central members. Already in 1948, just a year or two after arriving in California, Blackman was organizing composition contests to attract composers to create new music for the synagogue. Blackman was seeking to draw the attention of Jewish musicians working in Hollywood to efforts focused on the community. [1] One of the key undertakings of the Jewish Music Council was producing concerts. The Jewish Music Council concerts that Blackman and his colleagues, including Cantor Nathan Katzman, produced took as their goal creating a sense of connection between the organized Jewish community and Jewish artists working in Hollywood. These concerts also had the purpose of trying to burnish the dignity and professional reputation of the cantorial trade through the association of cantors with prestigious artists. The issue of labor rights for cantors seems to have been linked to other social justice issues, namely the civil rights movement. In one of their landmark concerts held at Temple Beth El on June 17, 1953, to an audience of 1200, the Jewish Music Council invited the composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco to create a new piece, a cantata titled “The Queen of Sheba.” [2] The premiere was performed by the African American soprano Georgia Ann Laster, winner of the prestigious Naumberg Foundation Award in 1952. [3]

Castelnuovo-Tedesco was a Jewish refugee from fascist Italy who established himself as an important figure in classical music on the American West Coast. A prolific composer, his work embraced a variety of Jewish themes over the course of a long and commercially successful career. [4] No recording survives of the original cast singing “The Queen of Sheba,” but the title and casting suggests a fascinating overlap of the exploration of Jewish and African diaspora themes. However, a recent performance by The Ridgewood Choral from 2012 has been posted to YouTube, offering an opportunity to hear the music and imagine the impression created by its all-female vocal ensemble in the context of a Jewish community that still formally rejected women’s voices as prayer leaders, even in the liberal movements.

Other pieces by Castelnuovo-Tedesco have been recorded by the Milken Archive of Jewish Music, including his evocative set of organ preludes based on prayer melodies composed by his grandfather, “Prayers My Grandfather Wrote.”

While the material traces of this particular collaboration are thin, I would suggest that for Blackman, featuring an African American singer in the premiere of a piece at a concert that had the goal of elevating the professional status of cantors was intentional. Both the pursuit of labor justice and the goals of integration and civil rights for African Americans resonated as issues that were at the forefront of American life and were keenly felt in the Jewish community by activists. Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s identity as a refugee from fascism resonates in this historical vignette; for Jews in America to make good on the promise of liberty that America offered as a refuge from antisemitism, they were required to actively pursue justice projects that pushed at the limits of America’s promises. With his unflagging energy and showman’s disposition, Cantor Blackman had the personality and devotion needed to influence people in his world towards his goals of political reform.

Rather than a surprising juxtaposition or an exception to the rule, the confluence of elements presented at this premiere concert reinforce each other as signs of the political orientation of Cantor Blackman and other members of his community at this historical juncture. The refugee composer Castelnuovo-Tedesco and the pioneering African American soprano Lester working together on a concert spearheaded by a progressive Jewish professional association speaks to the cultivation of a politic of activism and community building. At this moment, such active and engaged political organizing was embodied by multiple actors in the Jewish community, including Blackman and his professional cohort in the emerging post-war American cantorate.

NOTES

[1] See “Prizes Offered for Compositions for Sabbath Services,” B’nai B’rith Messenger (December 3, 1948), 13. Blackman discusses his outreach to members of the Hollywood music community in his interview with Levin.

[2] See “Strelitzer to Conduct Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s ‘Queen of Sheba,’” B’nai B’rith Messenger (June 5, 1953), 12.

[3] See “Georgia Ann Laster (1927-1961),” African Diaspora of Sacred Music & Musicians [website].

[4] See “Biography,” Mario Castel Nuovo-Tedesco [website].