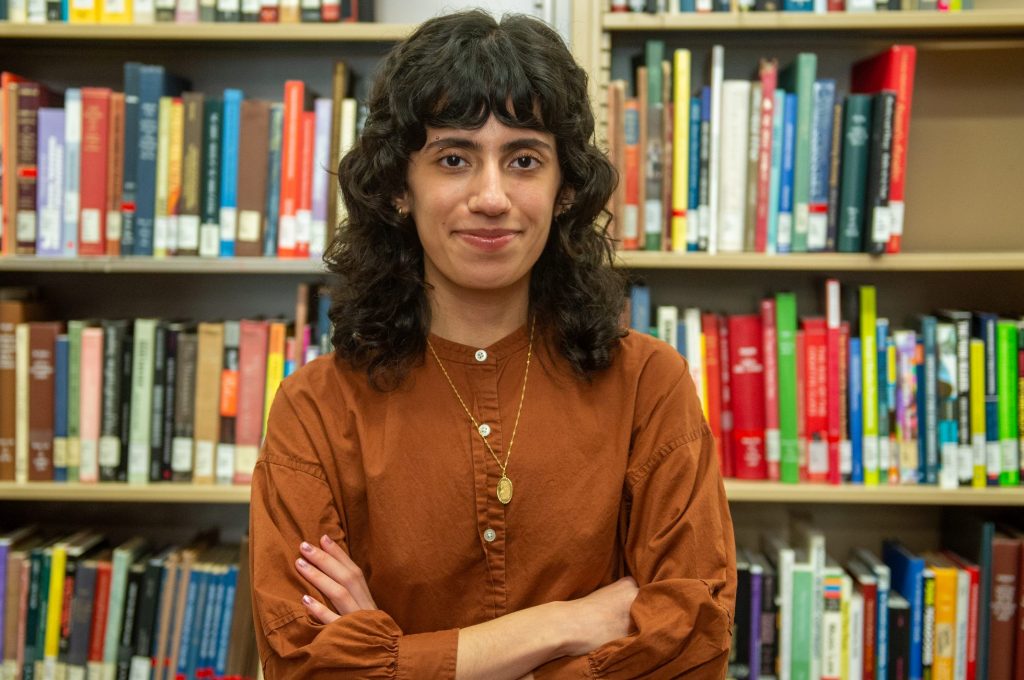

When Lily Shababi began her doctoral training in musicology at UCLA, her research mainly concerned American experimental art music of the late twentieth century. But a fascination with the niche world of hyperpop changed her direction.

“Adjusting to living in LA and starting grad school can be difficult,” said Shababi. “And so I immersed myself in the hyperpop music scene as a way of getting to know the city and build community. The more I did, the more I wanted to learn.”

Shababi’s interest has turned into a fervent research topic. She presented her most recent paper, “Culturally Situating Trans-Femininity through Hyperpop’s Technologically-Processed Vocals” at the Pacific Southwest Chapter of the American Musicology Society’s 2023 conference. A panel of judges selected her paper for the Ingolf Dahl Award, given for the best student paper read at the annual meeting of either the Northern or Pacific Southwest chapters of the American Musicological Society.

“It’s been fifteen years since one of our students has won the award, however deserving many others have been along the way,” said Ray Knapp, distinguished professor of musicology. “We’re really proud of Lily!”

Hyperpop is a genre label for alternative pop music known for maximalist electronic production. As with most subcultural genres, its roots extend much further than attempts to classify it. The label “hyperpop” was only adopted after the duo 100 gecs launched its viral album 1000 gecs in 2019. Key to 100 gecs sound was the use of vocal processing softwares to tune and pitch-up the vocals of the duo’s singer, Laura Les, a trans woman.

“I had heard “money machine” back in 2019, which was 100 gecs’s first viral hit,” said Shababi. “So when I got to LA, I started looking for the hyperpop scene, and I found it at places like Heav3n and Subculture.” Subculture is a bi-monthly rave that features musical acts loosely associated with the hyperpop genre label. Recently profiled in The Rolling Stone, Subculture has become one of LA’s hottest tickets and a meeting ground where trans artists can interact with each other as well as their fans.

Shababi refined her research questions and methods with UCLA faculty. Nina Eidsheim’s research on listening and the various ways that listeners code race and gender into musical sounds also proved influential. Catherine Provenzano’s work on the uses of Auto-Tune in music helped give her a framework for interpreting how musicians and listeners experience and interpret various technological enhancements to music.

“Lily is willing to look at questions from so many angles,” said Provenzano, who mentored Shababi as a graduate research assistant. “With this project alone, she’s considered questions of technology, community, circulation, sound, reception, voice, identity, among others, and has always kept in mind the real people at the heart of what calls her intellectually.”

Shababi is no stranger to technology and music. She earned her BM with a focus in violin performance and composition from Cornish College of the Arts. Her compositions range from traditional chamber arrangements to experimental work with electronics and acoustic instruments. She continues to work with technology as she composes, taking “the Brian Eno approach” of playing around with software to figure it out.

Shababi’s award-winning paper explores trans musicians’ different uses of technology. 100 gec’s use of Auto-Tune and pitch shifting on Laura Les’s voice has changed over time. Nonetheless, some fans and critics associated Laura Les’s pitched-up vocals as a “trans sound,” reading it as an attempt to manipulate voice to overcome gender dysphoria.

“Essentializing the characteristics and sounds of trans music carries risks,” said Shababi. “It flattens the trans experience. It can misinform.” Shababi’s paper centers the voices of trans artists, whose use of tools to process voice vary widely. Even Laura Les’s use of Auto-Tune has changed from album to album, suggesting an evolving artistic process.

But the infinite complexity of trans artists’ use of technology is wiped out in curated Spotify playlists. As is often the case, popular appeal and mainstream acceptance has become the proverbial doubled-edged sword. Notoriety raises awareness of trans artists, but mainstream audiences are often unaware of how music they consume on playlists can turn trans artists into stereotypes.

“Lily isn’t interested in reducing anything,” said Provenzano. “She’s interested in undoing the reductions that get in the way of listening to the fullness of trans vocality. Lily is also continually courageous in approaching the ambiguity that so often accompanies our work. It’s that humility and that genuine curiosity that I think makes Lily’s thinking, and this project, so strong.”

Shababi’s work looks to recover the musicians involved and the ways in which their music communicates with one another. It opens up a space in the literature to think about artist’s intentions and to treat the music as something other than a commodity. It comes at a time when hyperpop is a leading force in popular culture.

“It’s an exciting and politically-charged topic,” said Shababi. “I’m very much writing a history in the moment.”