by Simone Salmon, Ph.D. candidate, The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music

Sephardic Jewish music of the Holocaust in Yugoslavia and present-day Greece

Histories of the Holocaust scarcely mention Sephardic Jews, while there is even less documentation of Ladino music when compared to that of Yiddish, German, and Polish songs resulting from the Jewish experience. While there are many Yiddish songs that depict the Jewish experience of the Holocaust, there are just a handful of Sephardic songs written in Ladino that do the same by Sephardic Jews living in the United States. The songs you will see below are not the only Ladino songs associated with the Holocaust; rather, these songs were commercially performed, recorded and/or produced in America. The familiar melodies, themes, and vocabularies served to connect survivors after the experience of such overwhelming tragedy. To contextualize these songs, I have built a brief history of the ways in which Hitler’s Final Solution transpired in the Balkans. Part 1 contains music from Yugoslavia and Greece and Part 2 contains music from Greece and Turkey.

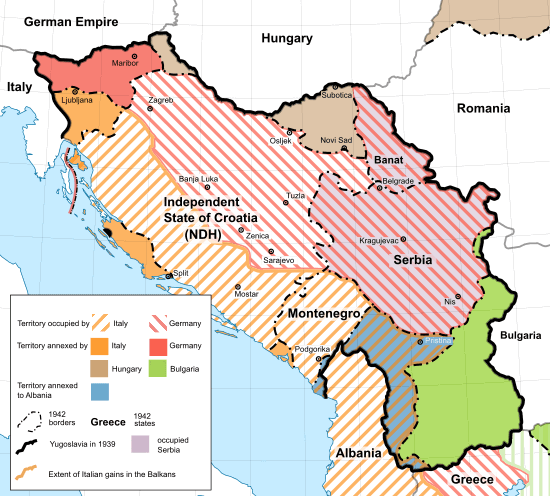

Yugoslavia and Greece were not part of the Italian-German Pact of Steel in 1939 that promised mutual aid. As outliers, both countries were invaded by Germany in 1941. During the brutal occupation of Yugoslavia, attacks on Jews, Roma/Sinti, Communists, liberals, and anti-German nationalists were rampant, so much so that Serbia became “Judenrein” very early in the unfolding of Hitler’s Final Solution. Yugoslavia was divided into two parts: the northern half was occupied by Germany and the southern half was annexed by Italy.

The famous Sephardic musician Flory Jagoda (1921-2021) was born Flora Papo to a Jewish family that had migrated to Sarajevo from Turkey.[1] She was just sixteen in 1941 when her Croatian stepfather gave her false papers and put her on a train from Zagreb to Split, located in the southern half of Croatia that was a separate Catholic state gifted to Italy by Germany. During her journey, Jagoda played her accordion [2] continuously on the train to avoid having her papers questioned. After her mother and stepfather joined her four days later, the family was moved by the Italians to the Croatian island of Korčula for internment. [3] Jagoda stayed in Korčula until 1943, when Italy had capitulated to the Germans, causing Croatia to become a German puppet-state occupied by both powers. She and her family boarded a fisherman’s tugboat that took them across the Adriatic to the town of Bari in southern Italy where they were welcomed as refugees. It was there during her employment there that she met the American soldier who later became her husband. She moved with him to the United States and has since been celebrated as a National Heritage Fellow. Although her first instrument was an accordion, she resolutely changed from her Bosnian sound to an American aesthetic by way of the guitar in order to make the music interesting to young Americans. Below is her version of the song “Adiyo Kerida” (1989, click for lyrics translation), which today is popularly depicted as being about the Holocaust. In her songbook, Jagoda wrote, “Modern interpretations of this song have changed it from what I remember from the 1940s when this was the most loved song in Balkan countries, the hottest tango in town. It has classical attributes as well, since Giuseppe Verdi incorporated it into his La Traviata. We Sephardim feel that he borrowed the melody from us, although he did change the rhythm.” The melody was in fact borrowed from Giuseppe Verdi’s aria “Addio del pasatta,” made Jewish through the addition of Jewish lyrics.

The same song is used in many depictions of the Greek experience of the Holocaust including the Greek film Cloudy Sunday (originally Ουζερί Τσιτσάνης meaning “Tsitsanis’s Pub”) [6] about the experience of Greeks in Thessaloniki at the time of German occupation.[7]

Greece was invaded by Mussolini in October of 1940, but Germany took over the Italian military campaign and divided Greece into two parts: Northern Greece and Greek Macedonia (including Thessaloniki, which was not part of the Bulgarian occupation) fell under German military rule and Southern Greece (including Athens) was put under Italian occupation.

In Thessaloniki (known as “Salonica” to Sephardim), the Germans embarked on an enormous campaign of possessing and stealing libraries, schools, institutions, cultural centers, and synagogues. They managed to create a humanitarian disaster in Greece, stealing the fish as fisherman pulled them from the sea, taking vegetables and taking mineral resources. This disaster affected Jews as well as gentiles. Jews experienced a social death in which they were forced to wear the yellow star, were pushed out of work, and lost their possessions due to the Aryanization of property. Most of the Jews in northern Greece were under direct German control. Communities pled with the Greek authorities and attempted bribes (the Salonican community was actually successful in getting Germany to release 7000 German workers in 1942). The chief rabbi in Thessaloniki tried to convince Jews to go along with the German plan because he thought that it was the best course of action. In 1943, Salonica was the first city to go en masse to the death camps. 50,000 Jews were put on trains to Auschwitz where they were either gassed on arrival or subjected to medical experiments. Meanwhile in Greece there was an assault on the Jewish cemetery of Salonica, the largest Jewish cemetery in all of Europe. The cemetery was raised, and tombstones were used to pave the streets, to create steps for houses, were built into swimming pools, and were used in the erection of Greek Orthodox churches throughout the city and Aristotle University of Thessaloniki on the site of the cemetery itself. Fewer than 2000 Greek Jews survive the war. Zamboni, an Italian diplomatic consul appointed in 1942 in Salonika, smuggled ~250-300 Jews to Milan under provisional passports. Greek Jews suffered the highest death rates of any national group of Jews in Europe during the second world war. Approximately 90% of Jews in Greece were killed, with Jews in Thessaloniki and the entire region of Macedonia suffering a 98% death rate.

The island of Rhodes had remained under Italian control from the first world war until Germany occupied the island in 1943. Jews who were not Turkish citizens were incarcerated in Haidary and deported to Auschwitz in 1944. These were the last of the German deportations from Greece.

Judy Frankel (1942-2008), a collector and performer of Ladino music, learned this setting of the “Hatikvah” melody from Maurice Levi, Sara Levi, Renée Levi, Stella Levi, [8] and Selma Mizrahi. [9] The melody of “Hatikvah” originally came from a madrigal by 17th century Italian tenor Giuseppe Cenci (Giuseppino de Biado). It had been made famous throughout Renaissance Europe and was adapted from its Romanian variant by Samuel Cohen, a 19th century Moldavan settler in Ottoman Palestine, who set the melody to the Hebrew poem by Naftali Herz Imber. The lyrics of the following song, “Fiestaremos” (click for translation of lyrics), parallel those in “Hatikvah,” reflecting the Zionist sentiment felt by many survivors of the Holocaust: [10]

Despite its celebratory title, “Fiestaremos” proves tranquil and somber in its lyrics and musical treatment. Like Flory Jagoda’s “Adiyo Kerida,” “Fiestaremos” demonstrates the ways in which Jewish melodies and songs were lifted from their original Italian settings, changing the ways in which they were understood by local communities for the purpose of commemorating the Sephardic experience of the Holocaust in the Balkans.

Part 2 of the Balkan Holocaust series continues with songs reflecting the Sephardic experience of the Holocaust in Greece, Bulgarian Macedonia, and Turkey.

NOTES

- 2002. “Flory Jagoda.” National Endowment for the Arts.

- Accordions were called “harmonicas” because of their button system. Her accordion was made by Hohner, a famous harmonica manufacturer.

- Jagoda, Flory. 1993. The Flory Jagoda Songbook: Memories of Sarajevo. Owing Mills, MD: Tara Publications. 14. Had Italy not protected them, they would have been moved to a German concentration camp in the north.

- Ibid. 35.

- Ibid. I modified the last line of this translation from her songbook.

- Cloudy Sunday can be viewed on Kanopy, a streaming service provided to those that own a library card in the USA and Canada.

- The English title of the movie comes from a song by the same name (“Συννεφιασμένη Κυριακή” or “Synefiazmeni Kyriaki”) composed by Vasilis Tsitsanis about the German occupation of Thessaloniki. The film follows the story of this famous Rebetiko musician and several Jewish and Christian characters during the war.

- Frankel, Judy. 2001. Sephardic Songs in Judeo-Spanish: From the Notebooks of Judy Frankel. Owing Mills, MD: Tara Publications. 77.

- Ibid. 27.

- Much post-Holocaust music contained reference to “Hatikvah.” For more examples, see Werb, Bret. 2014. “‘Vu ahin zol ikh geyn?’: Music Culture of Jewish Displaced Persons” in Dislocated Memories. Fraühauf, Tina and Lily E. Hirsch, eds. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 75-96.

- Frankel, Judy. 2001. 77.