by Daniela Smolov Levy

An indefatigable democratizer, Oscar Hammerstein wanted to provide opera for the masses – in his words, to “give first-class opera at prices within the reach of everybody.” [1] For the nearly forty years between 1871 and 1910, Hammerstein suffered, as the press put it, from the bite of the opera fly: all he wanted was to produce opera. Hammerstein had started out as a poor German-Jewish immigrant in the cigar industry, working his way up to become a wealthy New York businessman and opera mogul. While historians have chronicled Hammerstein’s prominence in the mainstream opera world, no study has yet examined his influential cultural presence among immigrant audiences, particularly Yiddish-speaking Jews who lived downtown on New York’s Lower East Side.

Hammerstein’s rags-to-riches story no doubt appealed to Yiddish speakers, who, along with other immigrant groups, especially Italians, were an important constituency for any opera impresario in early twentieth-century New York. Hammerstein’s rhetoric of democratic access – he described himself as the “Little Man Who’ll Provide Grand Opera for the Masses” – was particularly attractive in Yiddish circles. [2] But when Hammerstein finally struck operatic gold with the success of his Manhattan Opera House in 1906, it quickly became, paradoxically, an elite institution and a rival to the venerable Metropolitan Opera. (The two houses – the Met on 39th St. and Broadway and the Manhattan at 34th St. and 8th Ave. – were both considered “uptown” by the standards of the time and only a ten-minute walk apart.) Yet Hammerstein persisted in promoting his endeavor as a non-snobby alternative that still provided the most star-studded opera money could buy. And he certainly spent plenty of it – as did the Met in the massive opera war that ensued between 1906 and 1909 as both companies vied to secure the biggest names in the opera world. The fighting made for great copy as both the English- and Yiddish-language presses reported with delight on the squabbling over stars and the court battles. The conflict reached fever pitch in 1909, by which point Hammerstein had begun secret negotiations with the Met to be bought out in return for agreeing not to produce opera in New York for ten years. To maximize the price of the buyout, Hammerstein sought to expand his operatic empire as much as possible.

Part of this expansion included a summer season of what Hammerstein called “Educational Opera” at popular prices prior to the regular winter season in 1909. This was tailor-made to appeal to Yiddish speakers: high-class grand opera in a real opera house with quality singers given by a Jewish impresario – all at popular prices. Hammerstein even replaced the boxes with single seats to downplay the social element of operagoing. This blend of high and popular cultural spheres fit perfectly into the opera-inclined but anti-elitist bent of Lower East Side culture.

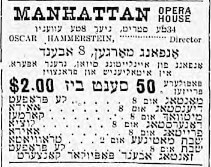

Hammerstein also made special efforts to appeal to Yiddish-speaking audiences by cultivating connections with Jewish circles, both in anticipation of the “educational” season and afterward. He advertised extensively in the Yiddish press (the Met did not). He included repertoire by Jewish composers or on Jewish subjects, even opening the educational season with Meyerbeer’s Le Prophète and the regular season with Massenet’s Hériodiade, which the Yiddish paper the Jewish Daily News described as “an opera that interests every Jew.” [3] Hammerstein’s oft-stated and long-held agenda of offering cultural uplift through opera, and especially his idea of an educational opera, resonated with the ideals of personal development and enlightenment (bildung and oyfklerung) prevalent in the Yiddish-language sphere. In his congratulatory letter to Boris Thomashefsky on the launching of his new Yiddish theatre newspaper Di yidishe bine (The Jewish Stage), Hammerstein noted that the Jews were “very important patrons of the Manhattan Opera House, and although they take mostly the uppermost seats, still their applause is more appropriate than that of those who listen below in the five-dollar seats,” observing also that “the success of a grand opera performance is very much dependent” on Jews. [4] Hammerstein even rented his opera house free of charge for the memorial benefit concert in honor of the recently deceased eminent Yiddish theatre playwright Jacob Gordin.

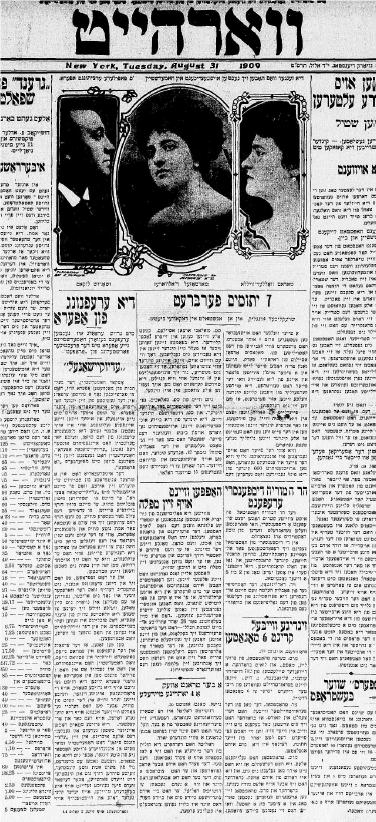

The Yiddish press reported frequently on Hammerstein’s activities, portraying him as a bold, unflappable, persistent Jewish upstart who was fighting back against that exclusive, aristocratic bastion of wealth, the big bad Met. In addition to his democratic orientation, Hammerstein’s own Jewishness was clearly an important part of his appeal to Jews. The Yiddish press embraced him as one of their own, a Jewish immigrant who had made it into the big-time.

The Yiddish press reported frequently on Hammerstein’s activities, portraying him as a bold, unflappable, persistent Jewish upstart who was fighting back against that exclusive, aristocratic bastion of wealth, the big bad Met. In addition to his democratic orientation, Hammerstein’s own Jewishness was clearly an important part of his appeal to Jews. The Yiddish press embraced him as one of their own, a Jewish immigrant who had made it into the big-time.

While Ivan Abramson brought the opera downtown to the people, staging high-quality popular price opera on the Yiddish-speaking public’s home turf, Hammerstein brought the people, the downtown public, uptown to the opera. Explicitly courting their patronage in both the educational and regular seasons, Hammerstein offered Yiddish speakers high-quality productions in an elite opera house while also making them feel welcome by finding ways to cater to their social and cultural preferences. In large part through coethnicity, Hammerstein connected Yiddish-speaking immigrant Jews to the glamorous opera scene, integrating them into the elite opera sphere. Even if this approach was self-serving in trying to maximize his audiences, Hammerstein still made Jews feel like they belonged in his opera house, not merely marginalized outsiders grudgingly being admitted into elite precincts. Hammerstein thus brought the elite and popular realms together, eliminating the snobbishness of the elite opera and making it accessible while retaining its allure and prestige.

NOTES:

[1] “Opera for the Masses: Hammerstein Plans Preliminary Season at Low Prices,” Washington Post, January 18, 1909.

[2] Anna Steese Richardson, “‘I’m the Little Man,’ Says Hammerstein, ‘Who’ll Provide Grand Opera for the Masses,’” New York World, Theatre Section, January 21, 1906.

[3] Jewish Daily News, November 19, 1909.

[4] Di yidishe bine, November 19, 1909.

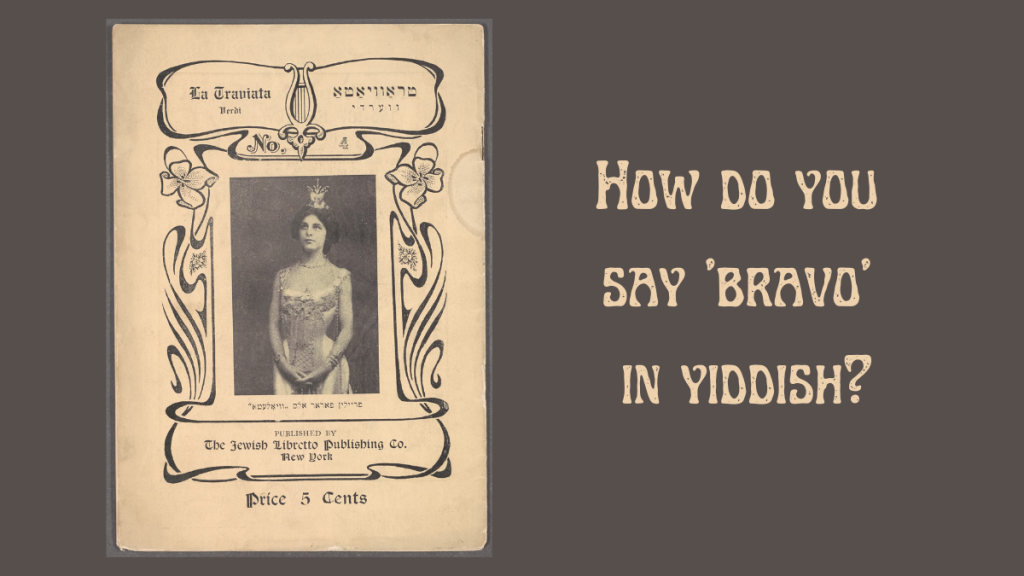

Note: This post is the second in a five-part series based on the five lectures I am giving at UCLA (via Zoom) between January and May 2022, “How Do You Say ‘Bravo’ in Yiddish?: Italian Opera for the Yiddish-Speaking Masses in Early 20th-Century America.” Sign up for the lectures.