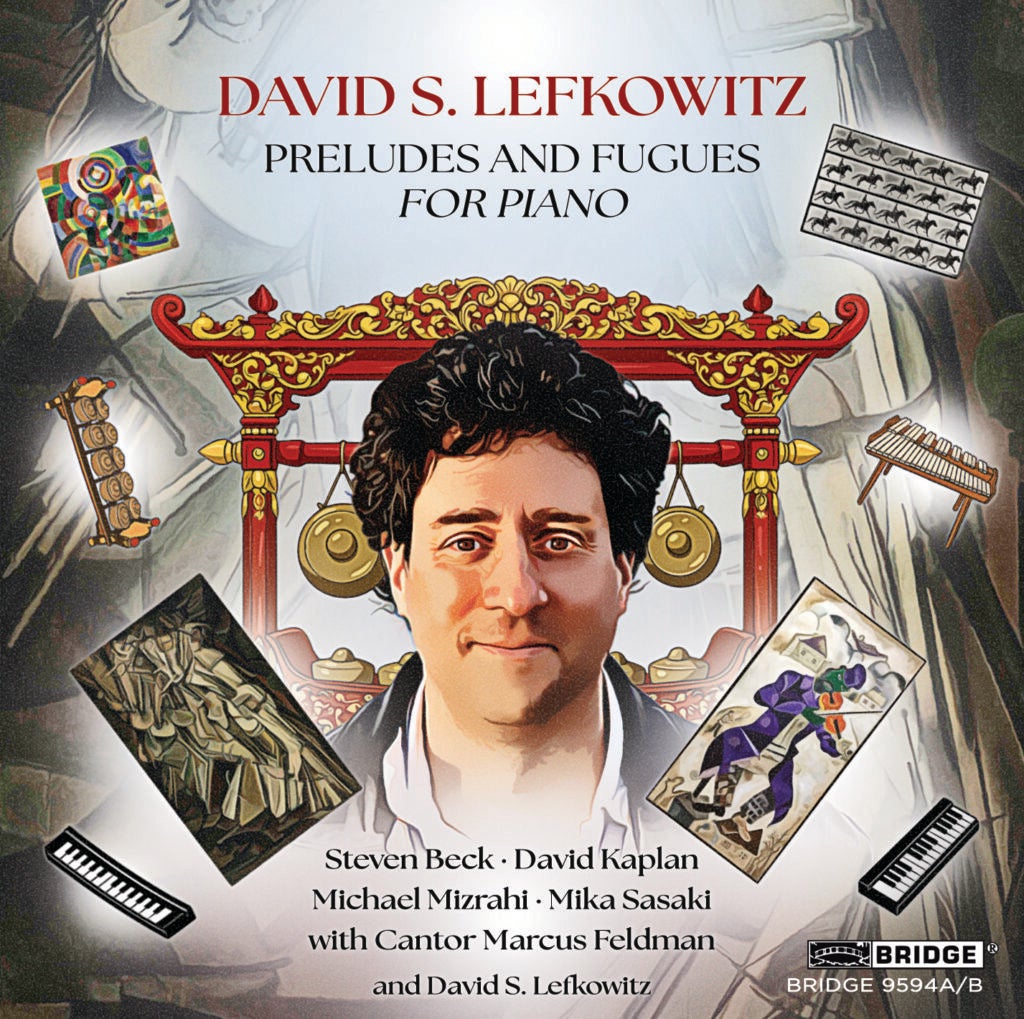

On a bright, summer Sunday in Westwood, scores of people convened at the Spanish revival home of David Lefkowitz, composer and professor of composition and music theory at The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music. They had come to celebrate the release of Lefkowitz’s latest recording project, two books of preludes and fugues.

But for the moment, they were watching him destroy his piano.

It hadn’t started this way. The guests had initially taken seats around Lefkowitz’s 1916 Steinway grand to hear David Kaplan, Shapiro Professor of Piano Performance at the School of Music, perform several selections from the double album. But the end of the recital did not turn out to be the end of the event. Lefkowitz tantalized the audience by playing a recording from his new album. The track hardly sounded like piano at all. Rather, it sounded as if the piano was accompanied by percussion, string bass and bells.

How had he achieved these sounds? Lefkowitz, who gamely explained that it would take far too long to “prepare” the piano for an afternoon recital, offered to give a short demonstration. He retrieved an armful of objects which he laid on the piano bench. Lefkowitz then took two machine screws from the pile, held them up and said, “Let’s destroy the piano.”

As Lefkowitz began working the machine screws in between piano strings, guests peppered him with questions. When had he started composing?

“I wrote a fugue during lockdown, back in 2020,” said Lefkowitz, hunching over the piano. “And I liked it well enough that I wrote another and another. Then I figured I might as well write the whole cycle of 13.”

Another guest asked what a fugue was.

“It’s a musical form that dates back to the Renaissance.” said Lefkowitz. “The fugue involves one melody which is introduced and then is repeated in separate voices, which are introduced on top of one another. It creates a wonderful counterpoint. And eventually, composers added a prelude that would introduce the theme for the fugue. This reached its height with J.S. Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier and Art of the Fugue. But I’m doing things a little differently than Bach.”

That was a calculated understatement. Lefkowitz’s first book of fugues is subtitled “Expanded Universe” and plays fast and loose with the form’s conventions. Themes are sometimes introduced at the same time rather than in succession. Lefkowitz invented novel modes (scales), some of which completely explode the traditional eight-note scale familiar to Renaissance and Baroque composers. Lefkowitz’s Prelude and Fugue No. 6, Book 1, for instance, uses a 22-note mode that spans six octaves. The notes are close together at the center of the mode, but spread out the further one gets. The effect is hypnotic—the piano seemingly floats on air and then runs upon the earth as voices converge and then separate.

“Once I had finished the first complete cycle of preludes and fugues, I thought to myself ‘well, I’ve already destroyed the concept of a fugue, so what can I do next?’ And then I thought ‘how about I destroy the concept of solo piano?’”

To demonstrate, he tapped a piano key that connected to the screw, which he grasped and moved slowly, increasing the resonance until it produced a high-pitched mechanical hum, almost synth-like.

“I love that sound, that kind of electronic sound,” said Lefkowitz. “I use screws in Prelude and Fugue No. 8, which was inspired in part by the paintings of Marcelle Cahn, a French artist who held in Strasbourg during World War II. There was something about this that just sounded very French to me.”

Lefkowitz picked up a flathead wood screw and worked it between two different strings. He talked as he worked. “I spent at least a few hundred dollars on this stuff. In fact, there was a man at Anawalt Hardware who got to know me. I would describe things to him, and he would say ‘oh, you want the brass screws, come over here.’”

Not everything came from the hardware store, however. Lefkowitz held up other items that he used in various fugues—kitchen sponges, golf tees, a clothespin and towels. “If you lay enough weight on the piano strings, it gives them a sound almost like a bass drum.” He retrieved from the piano bench a block of four decks of cards, held together with scotch tape, and leaned forward to lay them on the bass strings. Then he punched the keys, producing a flat, muffled sound. “I used that in Prelude and Fugue No. 3, which I named “‘Drums.’”

He was also asked if he had been in search of particular sounds for his compositions.

“Really the sounds found me,” said Lefkowitz. “I just experimented to produce sounds, and then they gave me ideas. The percussion sounds worked well not just in Fugue No. 3, but also in Prelude and Fugue No. 7, which I named ‘Funk.'”

Someone was curious if any other composers had ever manipulated a piano in this way.

“Oh yes. John Cage may have been the first to experiment with it,” said Lefkowitz. “He used mainly screws, bolts, some rubber stoppers. But as far as I know Cage didn’t use chopsticks. And chopsticks come in different materials, different kinds of wood, some with lacquer. They come in different sizes. Each type can make a very different sound. So, I spent many hundreds of dollars buying Chinese food and Japanese food, and swiping the chopsticks,” said Lefkowitz. “Sometimes you have to suffer for your art.”

Lefkowitz produced several pairs of chopsticks and began working them into the strings.

“These are bamboo, they work pretty well. These are balsa, and they sound different. But my favorite for sure are the ones with the lacquer.” He touched the keys to demonstrate each different sound.

“To me, they sound like Chinese temple bells,” said Lefkowitz. He took hold of the lacquer chopsticks and dragged them through the strings toward the piano keys. The placement matters, he explained. He hit the piano key, then moved the chopsticks back up to their original position and hit the key again. “Do you hear it?”

The crowd around the piano leaned in to listen. The note sounded like a regular C#.

“It’s hard to hear above the noise,” said Lefkowitz. He touched the key again, then moved the chopsticks and played the note again. Still no difference. The guests looked first at each other, then back to the piano.

“Ah!” said Lefkowitz suddenly. “I was playing the wrong key!” He brought his finger down on a different key. The resulting note sounded, unmistakably, like a temple bell.