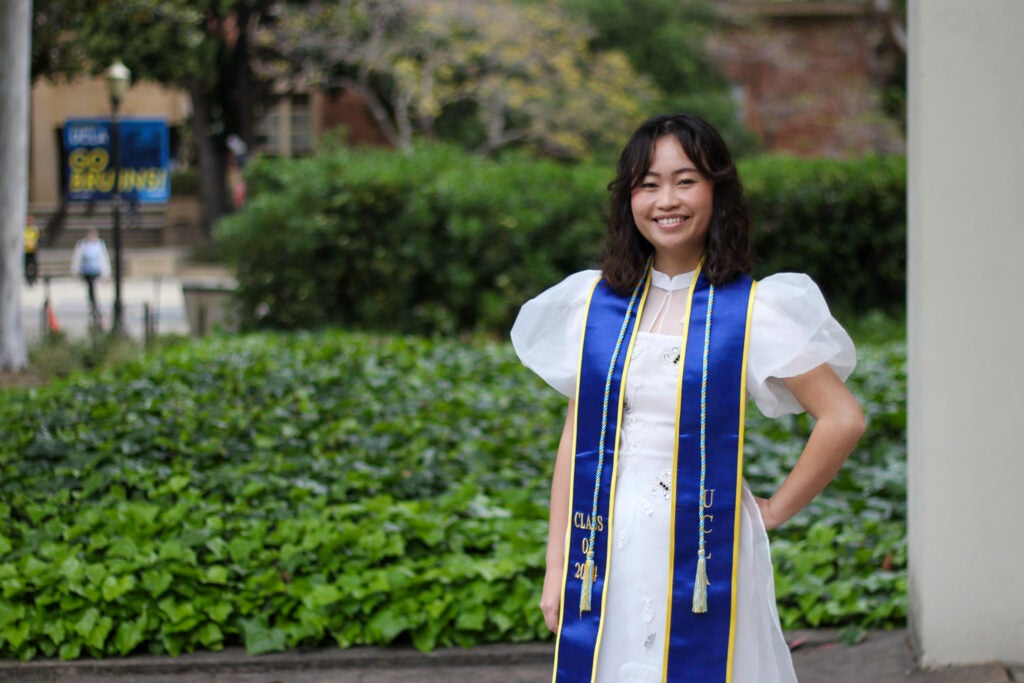

Ashley Dao has a habit of making the news at UCLA. This year, she was the first undergraduate student ever selected as an honorable mention for the Ingolf Dahl Award, given by the Pacific Southwest Chapter of the American Musicology Society. (She is also the first honorable mention for an award for which the criteria is that you be a graduate-level student.) This year she also won a campus-wide award for leadership from the UCLA Office of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, the Dean’s Prize for Excellence in Research and Creativity, and the UCLA Music Library Prize for Best Project on Music after 1900. The prior year, she became the first UCLA student (in any discipline) since 2015 to win the prestigious Beinecke Scholarship, which provides substantial support for students in the arts, humanities and social sciences. Her academic papers are accepted at scholarly conferences around the country. For three years she has served as the editor-in-chief of MUSE: An Undergraduate Music Studies Journal. She is responsible for bringing Corey Harris, American blues musician and MacArthur Fellowship winner, to campus and helped organize the Jacob Collier masterclass. With Dalton Mumphrey, also graduating in 2024 in global jazz studies, she co-founded the Schoenberg Art Walk, a meeting of artists across UCLA, now in its second year.

Ashley hails from Garden Grove, California. The descendant of refugees and immigrants from South Vietnam, she began playing music early and discovered a passion for piano, and then for music studies. She graduates this year with a bachelor’s in musicology.

# # #

What was music like for you growing up?

When I was a kid, I had a toy keyboard, and I loved playing it. I had a real affinity for it. By the time I sat down at a real piano for my first lesson, I already had some of the notes in my hands. Music is also a big part of my cultural heritage, so it’s important to me.

Break that down for me. What is it about your cultural identity that connects with music?

In my research and writing, I talk about how the history of South Vietnam isn’t really told, and it doesn’t live anywhere, institutionally. It’s not in Vietnam, because of the government there, and it really isn’t treated carefully in American universities. Growing up, learning the music in my community was a way to learn more about my family, and about my roots.

I also really loved classical music as a child. I loved Debussy, Ravel, all the French impressionists. I still do. I know that’s a little silly.

Silly?

The irony. (laughs)

Fair enough! Debussy gets a lot of attention for his revolutionary music. What about the French Impressionists resonated with you?

I enjoy the color of the music. Ravel’s Daphenis et Chloé is my absolute favorite orchestral music. The orchestration is just so lush. It has influenced a lot of my own composing, when I do that every now and again. I spent four years in music courses here, and no matter how many tools I develop, I still come back to color and harmony.

When I was little, I admired my sister for taking piano lessons. I was excited to play. And then I started participating in competitions and playing in ensembles. I played alto saxophone in the concert band, and later was a drum major. I learned violin my freshman year of high school and joined the string orchestra. Then I began conducting and taking leadership roles in the ensembles. Plus, I was already teaching music lessons. It really started to become too much.

Did you burn out?

Music became survival for me, and it stopped being enjoyable.

When did that change?

I think things shifted when I started teaching music theory, which I first picked up in middle school. I was so attracted to music theory. There are a hundred different ways to teach one thing to a student, and that’s how you build connections with a student. That reignited my passion for music.

Music education seems to be a passion for you.

I thought I would go to college to study music education, and I always envisioned myself finishing college and then going right into a K-12 school to teach. In fact, I applied to colleges to either study music performance or music education. UCLA was the only school that I applied to as a musicology major.

You’re an accidental musicology major?

Yes! I read some amazing literature on feminism and music criticism, so I was interested in the subject. I went out to UCLA to attend one of the musicology department’s distinguished lecture series, and I sat next to [musicology professor] Elisabeth Le Guin. I knew who she was, of course, but I was really shy and didn’t introduce myself or anything. But she asked me who I was, and was surprised to find out I was a high school student. She introduced me to Professor Mitchell Morris and they invited me to the reception for the lecture. I met some of the graduate students, and I really liked the environment.

To share my passion with others, was not something that I’d had before. It actually woke me up to the fact that I had always been a musicologist. Even as a child I was analyzing the structure of music and the theory behind it, and I was always curious about music’s historical and social context, and how it was shaped by politics and notions of identity. I was always thinking like a musicologist, I just didn’t have a word for it.

Did that feeling continue throughout your undergraduate years?

Without a doubt. I made great friends in my first year, including graduating seniors who were great mentors. We started an informal book club. One of the most exciting books we read was [musicology professor] Nina Eidsheim’s The Race of Sound. I found it really approachable, and I’m really interested in the intersection between music and critical race theory. All the books we read, they were great starting points.

I’ve also enjoyed learning about music and media, and popular music. We had meet-ups to talk about popular music and scholarship.

Which popular music did you discuss, at the time?

Thom Yorke, Bjork, the Carpenters.

How did your undergraduate work at UCLA challenge you or make you think differently about something?

When I arrived, I thought for sure I was going to work on physics and music. I took all the AP classes in high school, and I was fascinated by the idea of studying music as a science. But I think the way that physicists and mathematicians approach music as a field of critical study can be somewhat myopic and ignores the humanistic aspect of music. I lean more toward the humanistic side of the study of music.

We’ve talked about your research before. [Ashley Dao’s scholarly project focuses on the musical practices of the Orange County community of Little Saigon.] What is another project that you have going?

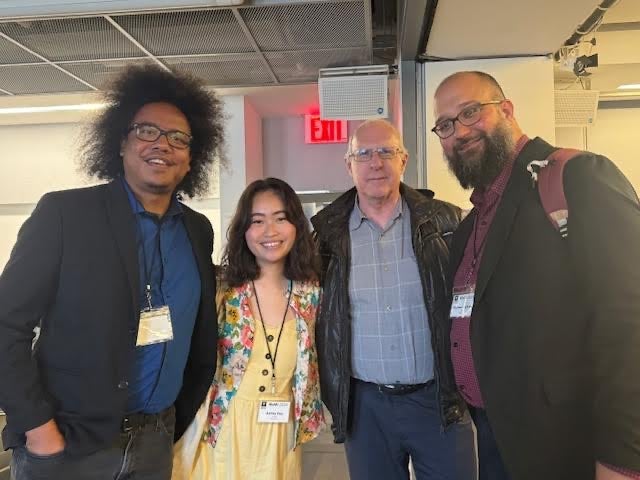

I’m flying out to NYU to give a paper at the Music and the Moving Image conference.* It’s about nostalgia and empathy in Todd Haynes’s Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, and how he represents her in the movie. It’s a great conference because it combines scholars across disciplines and professionals in the media industry—filmmakers, audio engineers, everyone.

What’s next for you?

Graduate school. But I’m taking a year off first. I want to work on some of my writing, maybe try to spin one of my projects into a book. But first, graduation!

# # #

*Music and the Moving Image is in its twentieth year as a standing conference, hosted by NYU Steinhardt and took place from May 24 to May 26, 2024. This interview was conducted before Ashley traveled to New York to give her paper, but published after its conclusion.