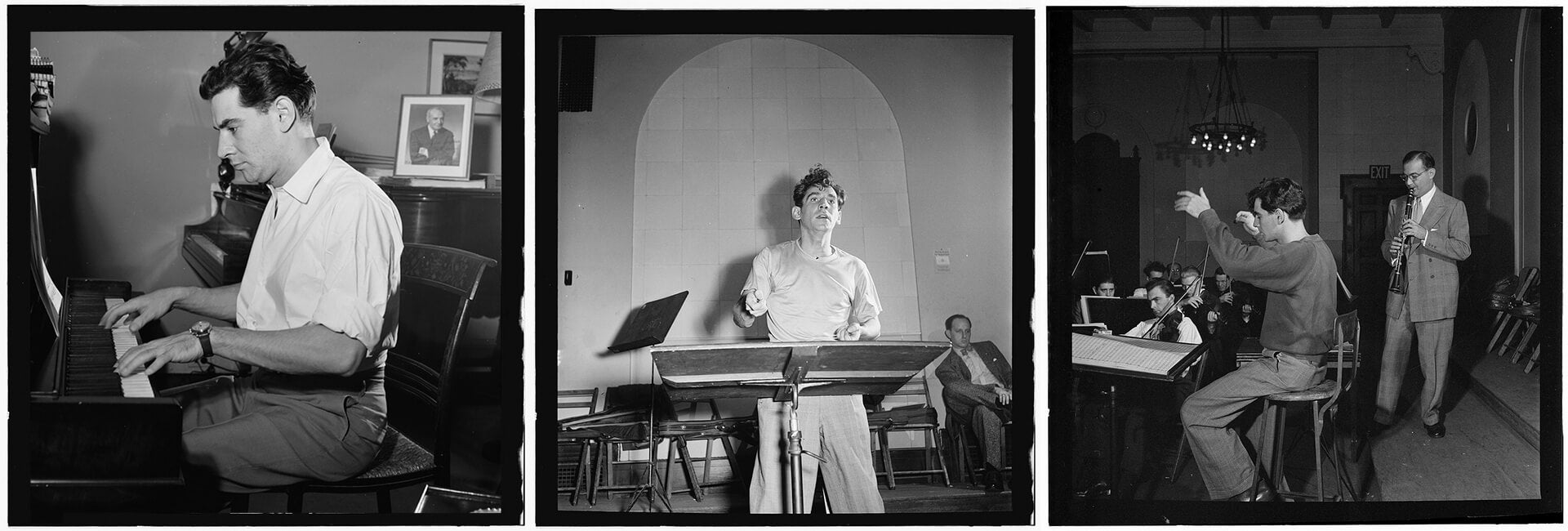

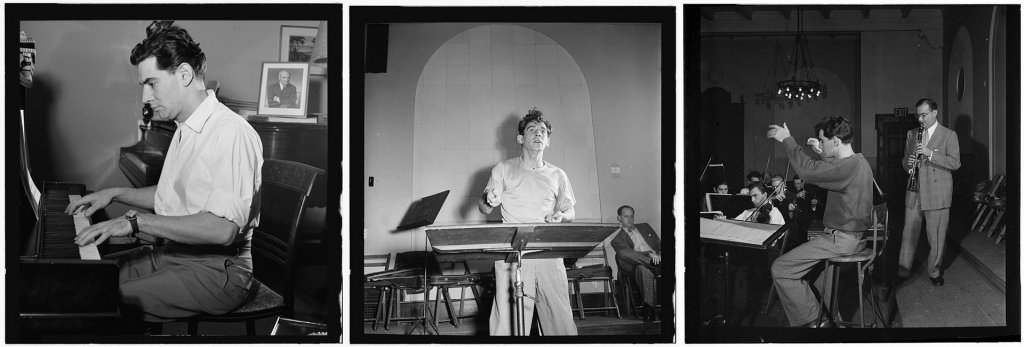

World-wide celebrations are underway honoring American composer, conductor and educator Leonard Bernstein, who died in 1990 and would have been 100 on August 25, 2018. A multitalented musician, Bernstein rose to international fame during his tenure as the music director of New York Philharmonic. He was a dynamo on the podium, and a prolific composer of music across genres, including opera, chamber and vocal music, orchestral works, piano music and ballets. His music also made its way into popular culture in Broadway hits and Hollywood films, including West Side Story and the film On the Waterfront.

Opera UCLA joins the global celebration with an evening dedicated to Bernstein’s theater music plus his late masterpiece SONGFEST, a collection of twelve beautiful settings of American poets, on Nov. 17.

Four professors in the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music share their thoughts and personal moments with “Lenny.”

Peter Kazaras, UCLA professor of music and director of Opera UCLA

I first met LB in person in his apartment in 1971. I was going to see the new production of Tristan und Isolde at the Met over Thanksgiving weekend, and my college friend Jamie Bernstein had invited me to a party at her house that night. I told her I was going to the opera and she said “So’s Daddy! You can go together! Why don’t you come for dinner first?” Um, sure.

I turned a corner and there was this extremely short man with an extremely low voice who said “Don’t tell me — you must be the world-famous Peter Kazaras.” I said, “And I have a pretty good idea who you are as well.” Huge smiles, welcoming handshakes, and it was off to linguini with clams. And Lukas Foss, who had just conducted that afternoon’s concert at the New York Philharmonic.

A riotous dinner ensued. We talked about Tristan, we talked about his proposed recording (still 10 years in the future at that point), and we talked about how Eileen Farrell (his dream Isolde) couldn’t sing the role because “she never had a high C.” I disagreed, pointing out that she sang a stunning high C in her recording of “Ozean, du Ungeheuer” — “the famous agogic high C!” as I described it. “Who the hell ARE you?” asked Lenny. “I’ve listened to a lot of opera” was my only response.

Then came the performance (pretty stunning — soprano Birgit Nilsson at her peak) and then my return to the apartment on East 79th street. This was pre-Dakota days. I was enjoying the party when LB returned at around 1:30 a.m. “Aha! I was hoping to find you here! Come to the studio with me!” And then I was interrogated as to what I thought and why I thought it. We went through each singer, rather meticulously. Then he said “How about Leinsdorf” (who had conducted). I demurred — no way was I going to discuss another conductor with him, let alone criticize someone! But he insisted — “I am asking you because I want YOUR opinion!” Well, ok, I thought, here goes: “I thought it all very competent, he finished at 11:57pm, a good three minutes before the midnight deadline at which overtime would kick in for the musicians, and it was clean and it worked. But it was not inspired, and it did not sound like Tristan to me.” “Aha! Precisely! That’s exactly it! Leinsdorf is totally competent, and that’s his strength and his downfall — this was not inspiring, it did not transport us to the other world of Tristan time.” He went to a harpsichord in the corner of the studio and started to play the Tristan Prelude from memory (of course) ON THE HARPSICHORD at 2 a.m. And as he played, he talked, guiding me through the piece. He insisted again and again on the need for limning “Tristan time” in a way that was very different from ordinary time. It was, of course, unforgettable.

Juliana Gondek, UCLA professor of music

I met LB in the early spring of 1984. I’d just returned from winning the Geneva International Singing Competition, which had brought me to the attention of Stephen Wadsworth, librettist and director for Lenny’s final opera, “A Quiet Place.” It was being produced in its revised form at La Scala and Kennedy Center during the summer of 1984. I was hired off a recording Stephen had heard to cover the lead soprano role of Dede, the adult daughter (and wife to Peter Kazaras’s character).

One day during Washington rehearsals for “A Quiet Place,” Lenny announced auditions for Sharks and Jets to sing on his upcoming Deutsche Grammophon recording of “West Side Story” in New York City. I won a coveted spot as a “Shark girl” and a few weeks later, a number of my “Quiet Place” chums and I found ourselves waiting in an upper floor hallway in Rockefeller Center outside the soundproofed orchestral hall of RCA Studios. Inside, a BBC documentary film crew was waiting with Lenny, a team of recording engineers and technicians, and a full symphony orchestra for the celebrated diva Kiri Te Kanawa to arrive for the project’s first morning session.

The minutes ticked by – 20….30….40 minutes with no “Maria” in sight, 80 musicians earning big bucks to sit doing nothing, and LB growing more “animated” by the minute. FINALLY, after an hour or more of wondering whether the session would be called off, those of us lined up along the hallway heard stiletto heels clicking ferociously on the linoleum from around the corner. Kiri Te Kanawa came into view, wrapped to the chin in a fur cape (on the hottest day of the year), accompanied by her assistant. As they swept past my pal Stella and me, I heard Dame Kiri rasp to her companion “What do I tell him?!” in a barely there, obviously hoarse voice. Stella and I stared at one another in astonishment, slack-jawed, eyes popped, and exclaimed “Oh my gosh! She’s VOICELESS!” Te Kanawa and assistant entered the orchestral hall and the door slammed shut behind them. After 5 or 6 minutes of silence, the door exploded open, and Miss Te Kanawa and assistant clicked ferociously past us again, back along the hallway from whence they had come and disappeared around the corner.

David Stahl, a brilliant young conductor mentored by LB, stepped into the hallway and announced that the session would commence shortly. Lenny seemed edgy and out of sorts, scowling and snapping at the sound engineers, but once that glorious orchestra began to play, he dissolved into grins, nods, “thumbs up” and began dancing on the podium to his own iconic music. The session in which we recorded “America” with the great American mezzo-soprano Tatiana Troyanos turned into a beach party. LB vamped, flirted, cracked jokes, and gave us his sexiest Chita Rivera imitation. He encouraged us Shark girls to yip and bark to our heart’s content and I’m tickled that I got a nanosecond-long improvised solo in the final edit: When “Anita” sings “An’ de bullets flying”, there I am with “Watch out!”

Richard Danielpour, UCLA professor of music

In the first week of March 1984, I remember Mr. Bernstein gave a concert with the Vienna Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall. This concert was one of the greatest I’ve ever attended. It included the Mozart 40thSymphony in G minor on the first half, and the second half was Mahler 4. I remember I was sitting up in one of the dress circle seats, where students often sat, and afterward I thought, “I’ve got to go back and see him.”

So I went to the dressing room, and he was sitting there in his robe with his cigarette in one hand and his silver goblet of scotch in the other. I said, “I have to ask you, how do you do it?” He put down his cigarette and scotch and said “you mean this–” and conducted a 4/4 bar. I said, “No, I mean IT, how do you get this magic to happen?” And he took a puff of his cigarette and said “You know, in the end, it’s all about love.” As a hungry 28-year-old composer, I said “You mean the love that you and the orchestra have for the music?” He said, “In a way.” I said, “You mean the love and respect that you and the orchestra have for one another?” and he said “Sort of, you’ll just have to stick around for 20 years and you’ll eventually get the idea.”

Many years later, back at Carnegie Hall, I had now met him; he had listened to my music. He said “whenever you finish a piece, just bring it to me and we’ll look at it together,” and that’s how my lessons were.

A couple of weeks after, he had said “Danielpour, I’ve been listening to your music and loving it.” I went back to another concert where he invited me for real, and it was Mahler 6 with Vienna. Again, I had to go back, and I could tell he was a little tired because it’s a hell of a work to conduct. He looked at me and said “Don’t you wish you’d written that?” and I said “Yeah!”

He told me a story about how he wasn’t getting it when he first started trying to conduct the Mahler 6th Symphony with the Israel Philharmonic. He was conducting it with Israel Philharmonic and the timpanist said “Maestro, why don’t you try to conduct the beginning like you’re trying to conduct a gestapo march.” He said, all of a sudden, he saw Mahler as a prophet who was in a way foretelling what was about to happen in Germany 25-30 years later.

He was talking about all this, and he said, “Bring me some music, come and visit, don’t be a stranger, but for now I’m tired, get out of here.” He took my hand in his hands as a rabbi would and kissed my forehead as if he was giving a blessing, and said “Go on, get out of here, you’re going to make a lot of people happy in the years ahead, go do it.”

Robert Fink, UCLA professor of musicology

Leonard Bernstein was the inescapable musical figure of my 1970s youth: I grew up, also Jewish, in his hometown of Boston. I knew firsthand many of the musical places and institutions that nurtured him (Harvard, the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Tanglewood), read his books, winkled tricky scores like Candide and Mass out of the local library to pound them out on the piano, and listened to his high-voltage recordings (Beethoven! Shostakovich!! Mahler!!!) for hours and hours on end. To say that Bernstein was the primary reason I became a music lover, then a musician, and finally a music professional, is not eulogistic hyperbole, but a simple statement of fact.

I did not realize that by the time I imprinted on Bernstein, the world of grown-ups was already getting tired of “Lenny.” He got saddled with blame for the curdling of Sixties “radical chic;” he was ostracized by serious composers because he could not—or would not—master atonal composition; and he seemed to lose his pop touch, too, as jazz gave way to rock, and aging hipsters like him became terminally uncool. It says something about our ideology of “great music” that, though we cannot resist celebrating the Bernstein centennial, some critics are resisting the man himself in terms that echo some of the least edifying, most “Bostonian” moments in the history of Western music. The party isn’t even close to over, and already critics are a little disgusted with their guest of honor. The familiar whispering starts: he was never that serious a composer, he lacks discipline, he panders, he’s shallow, glitzy, derivative, he borrows too much, wrote too fast, is irredeemably vulgar, too loud, too sweaty, too sexual, too…well, you know the rest. (Don’t make a shanda fur di goyim, Lenny.)

Leonard Bernstein is great because he continues to make a mess of our neat categories. It’s not possible to be the best composer, the most popular songwriter, and the most charismatic conductor; a TV personality, and a revolutionary, and a prophet, and everybody’s lover all at once. It’s like he won’t go away. He’s inescapable. But that’s why we are compelled to celebrate his 100th birthday. Happy Birthday, Lenny, have another piece of cake. You deserve it all.

Alternate Hero