by Simone Salmon, Ph.D. candidate, The UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music

American Sephardic immigrants created new Ladino lyrics for melodies from sources in Turkish, Yiddish, Hebrew, Greek and Arabic, recreating the multi-lingual atmosphere of their Ottoman homeland.

Songs in Ladino are frequently based on borrowed melodies from song sources in Turkish, Yiddish, Hebrew, Greek, and Arabic, reflecting the multi-lingual and cosmopolitan culture of the late Ottoman Empire. Popular melodies that exist in multiple versions in different languages continued to circulate among a subset of Sephardic Jews that immigrated to America in the years leading up to the Great Depression. In the same way that Jewish life was interwoven with the lives of other nationalities during the Ottoman Empire, Jewish life in America was connected to the lives of their neighbors in music and other cultural activities. Across generations and geography, Ladino [1] songs have long served as a bridge between diverse communities within the geographically dispersed Sephardi diaspora because Jews from different places of origin could recognize the same melodies and lyrics in one another’s music. Additionally, Ladino songs illustrated the ties between Sephardim and the broader cultures to which they belonged. These cultural connections are made audible in music through the technique of contrafact. In this essay, I will offer several examples of melodies and texts derived from the multi-lingual Ottoman cultural milieu that became important to Sephardi culture and the Ladino song tradition.

Contrafact, the process of imposing something new over something extant, was a process heavily used in the making of Ladino music. Melodies were often borrowed from surrounding cultures and Ladino lyrics were added to them. In some cases, the Ladino poetry was pre-existing, which is evidenced by unidiomatic accents in the Ladino lyrics, [2] or in many cases Ladino lyrics were composed for the specific melody, evidenced by parody lyrics seen in various tangos and foxtrots of the Turkish Ladino revival. [3] The following songs show us the ways in which Sephardic Jews borrowed melodies from the languages of Turkish, Yiddish, Hebrew, Greek and Arabic and made them their own.

From Turkish

In the same way as other Ottoman minority groups, Sephardic Jews appropriated the melody of “Kâtibim” (also known in Turkish as “Üsküdar’a gideriken”) in their day to day listening. While many argue that the following song’s melody originated in Turkey, it has unique lyrics in Serbo-Croat-Bosnian, Albanian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Greek, Romanian, Hungarian, Arabic, Persian, Indonesian, Bengali, Turkish-Urdu contrafact versions. Below is a Turkish version from 1949 featuring Safiye Ayla, one of Turkey’s most famous singers.

The first commercial recording of this melody in the USA was performed without lyrics by the famous klezmer clarinetist Naftule Brandwein. He titled it “Der Turk in America” (1924) and adjusted the melody to resemble “Hatikvah” as an act of Judaization.

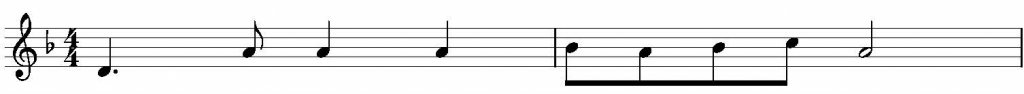

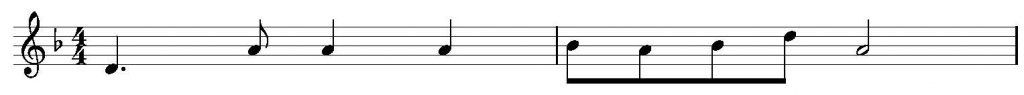

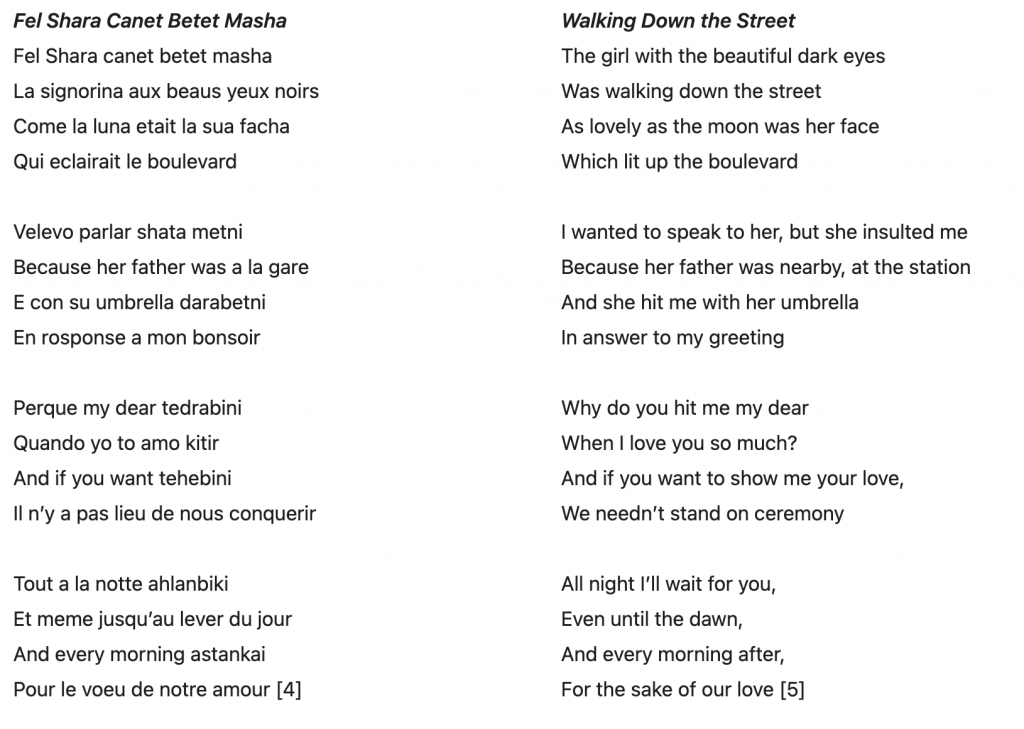

The following version was recorded by New Yorker Gloria Levy, the daughter of Sephardic immigrants from Alexandria, Egypt and Izmir, Turkey. “Fel Shara” (1958) is a Sephardic version of the original melody with exceptionally mixed lyrics that emphasize the cosmopolitanism of the Sephardic Egyptian population. Its lyrics are an amalgamation of Arabic, Ladino, Judeo-Italian, Judeo-French, Berber, and English:

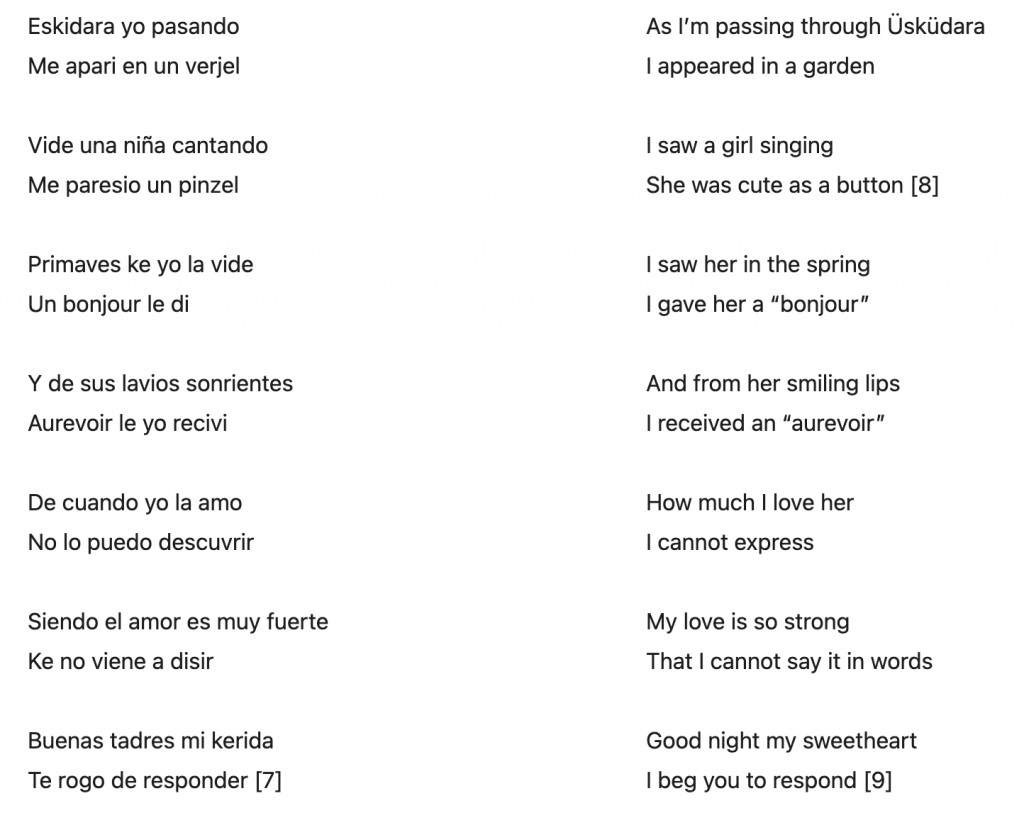

The melody was also adapted from its Turkish version by Sephardic Jews in the USA. Like those in “Fel Shara,” the opening lines of the verses are consistent with the melody of the original Turkish version. There is no date for the composition of the Ladino lyrics or even the first recording of the song, [6] but the melody was adopted by my grandparents, Isaac and Emily Sene, at roughly the same time that the Brandwein version was recorded.

All three versions were likely put together in the Lower East Side of Manhattan.

From Yiddish

Because the Lower East Side of Manhattan was quite small, there was some amount of Sephardic musical association with their Ashkenazi co-religionists. Reuben Doctor, a Jewish composer from Bessarabia, composed the cheeky Yiddish theater song, “Ich Bin a Boarder Bay Mein Veib,” which was recorded below by the famous Fvyush Finkel:

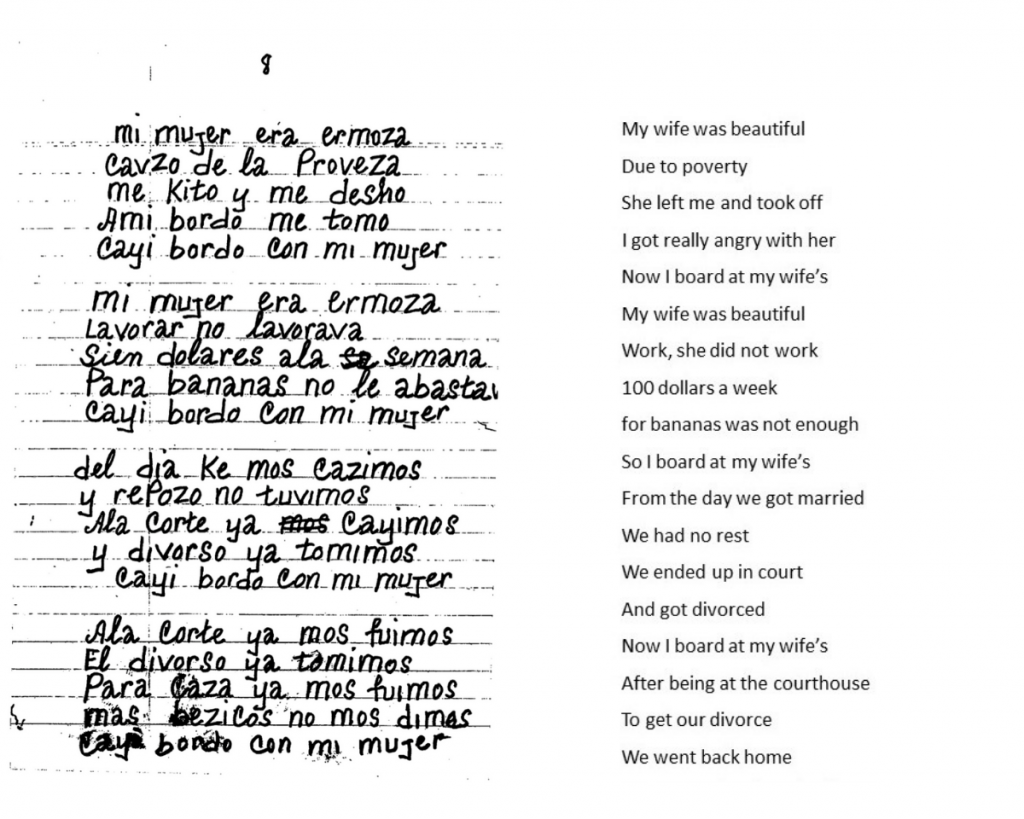

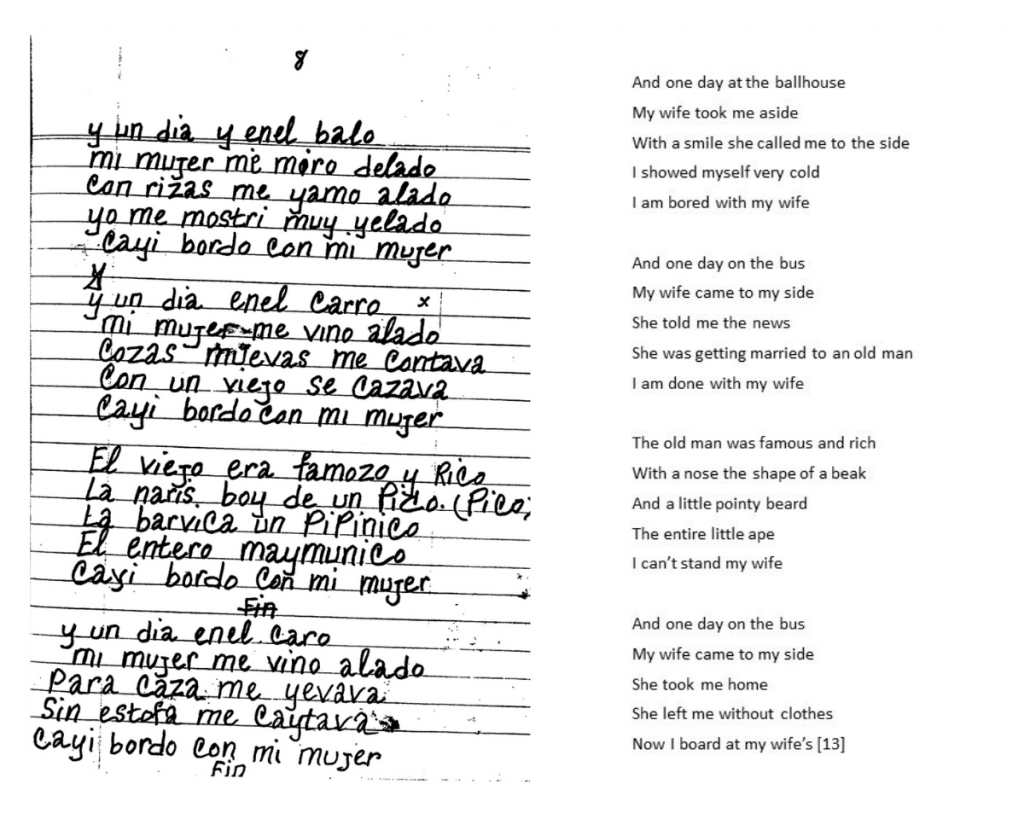

Emily Sene recorded a contrafact Ladino version in her notebook:

The phrase “cayer bordo” borrows from the English verb “to board,” but it is also a play on the Spanish pun “cayer gordo,” which means to find someone unappealing. The lyrics show that the singer is both paying rent to his wife and that he is fed up with her. By continuing to sing playful songs like these into the time of the Great Depression, Sephardim could enjoy themselves and temporarily escape the despair wrought by their low-paying jobs and increasing unemployment.

From Hebrew

Due to their joblessness and the misery of the depression in New York City, Isaac and Emily Sene packed up with their two daughters and moved to Los Angeles in 1942. Isaac developed a large following at his weekly “Turktown” picnics at Ladera Park (and sometimes Veterans’ Park) in Southern California as president of the Sephardic Cultural Club. Isaac frequently played “Turkish nights” and other Jewish cultural events in the Los Angeles area.

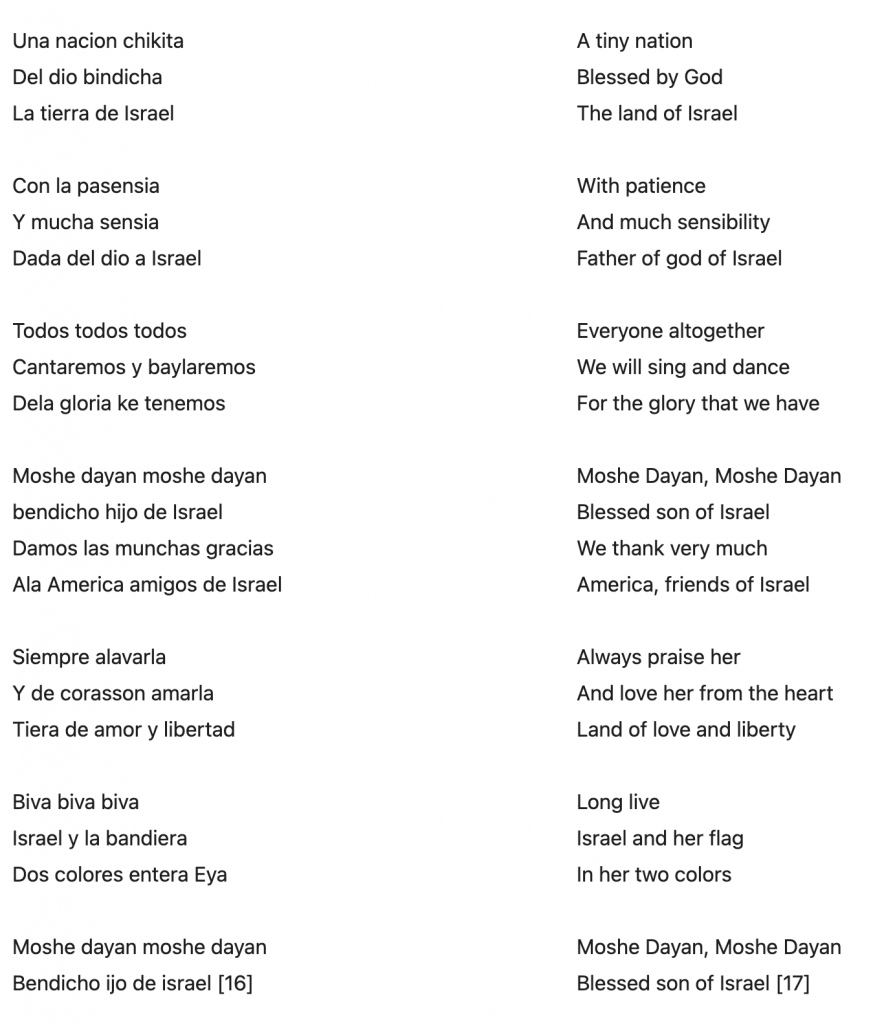

The following Hebrew melody of “Hava Nagila” was essential to every birthday, wedding, and bar mitzvah for Sephardic Jews in Los Angeles. Isaac Sene penned the Ladino lyrics and performed the song in both Hebrew and Ladino at Sephardic gatherings in the United States.

Two violinists accompany Isaac in Emily Sene’s recordings: “Tio” Selomo, [14] a man learning the violin who studied under Isaac Sene, and Hayk, [15] an accomplished Armenian violinist who accompanied Isaac during many performances. The second recording of Isaac’s birthday party shows that the violinist, likely Selomo, was not yet comfortable with the melody (or perhaps his instrument).

From Greek

Performing alongside Isaac Sene in the second half of the twentieth century at the “Turktown” picnics in Southern California was Jack Mayesh, a popular Greek-Sephardic singer and cantor. Mayesh was the most famous commercial Ladino music singer in Los Angeles. In addition to his downtown flower business, he owned the Mayesh Phonograph Record Company, which was the only Sephardic record label in Los Angeles. [18] Mayesh’s company typically used the title “discos españoles” (Spanish records) to incorporate songs in Judeo-Spanish and Hebrew. This particular record was described as “Spanish Oriental” on its label.

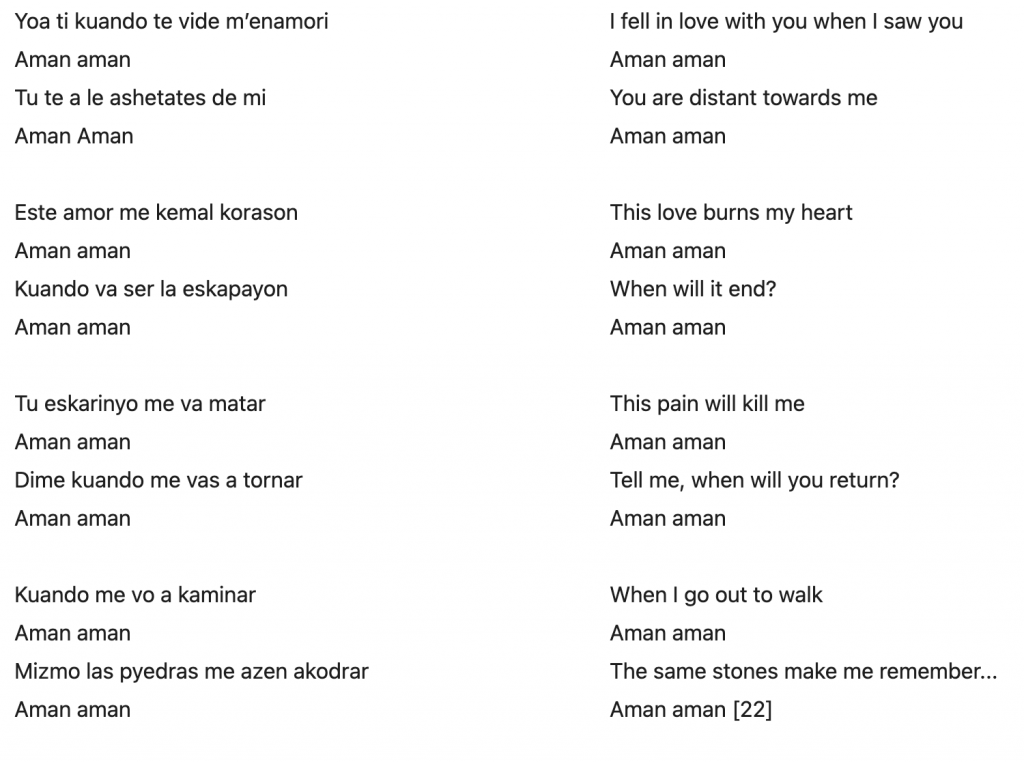

Mayesh’s secular recordings were almost always a product of contrafact; he took popular Turkish and Greek melodies and set his original Ladino lyrics onto them. He was perhaps most famous for his treatment of the Greek song, “To Kanarini,” sung in Turkish as “Ah Sevgilim Bülbülüm,” with Ladino lyrics. Here is a recording of Roza Eskenazi, a Greek Jew famous for her Rembetiko performances in Constantinople, singing “To Kanarini” in Greek followed by her version of “Ah Sevgilim Bülbülüm” in Turkish:

The following is a recording of Isaac Sene and his cousins singing the Greek version while in Havana (before Isaac was admitted to the United States):

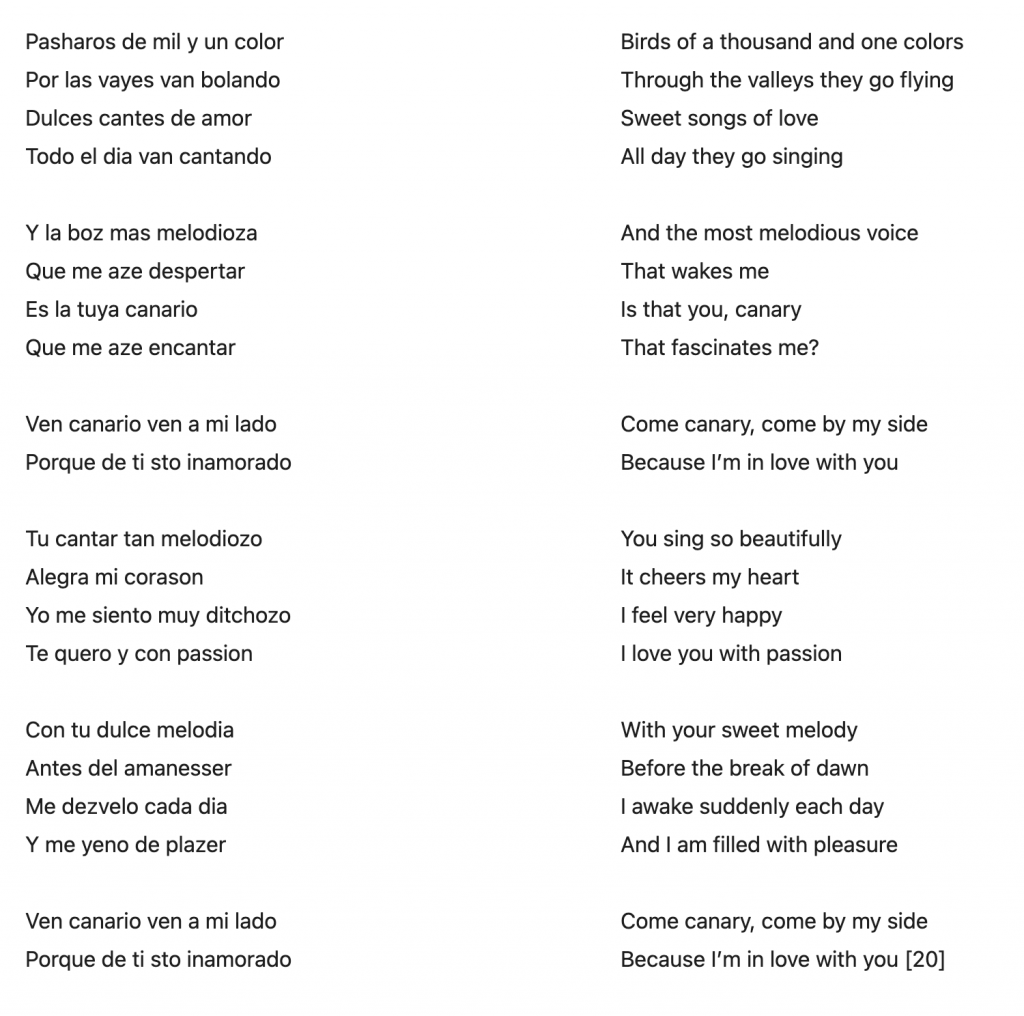

And here is Jack Mayesh’s version, “Ven Canario” produced by Me Re Records:

In the Turkish version, the lover is called a “bülbül” or nightingale. The nightingale has literary significance in that it represents love and death simultaneously. [21] It is said that the nightingale only sings when separated from its mate. The bird in question, however, changes to a canary in the melody’s Greek version. Mayesh’s Ladino lyrics most resemble the lyrics in Greek.

From Arabic

The final melody is in the Andalusian poetic form of the muwashshah. Historians have made differing claims about the era in which it was composed. The composition has been attributed to Lisan Alddin ibn Alkhateeb (1313 -1374), Sheikh Muhammad Abdul Rahim Almaslub (1793-1828), and Salim Al-Masri. The famed Lebanese singer Fairouz was just one of many to record it:

To the best of my knowledge, the first Ladino version of this song was not performed in America by Sephardim in the years leading up to the Great Depression. Although there are many Arab melodies with Ladino lyrics that have been in America for the last 90 years, I selected this melody in particular because an interview that I had with a Ladino musician inspired me to bring his lyrics to America. A Ladino version of this song was put out in Istanbul through the label Gözlem Gazetecilik Basın ve Yayın A.Ş. by the group Los Paşaros Sefaradis in 1995. Upon meeting Selim Hubeş, a member of the band that recorded this song, I asked him about the source of the lyrics. Hubeş told me that an Armenian in Istanbul taught him the Ladino lyrics!

The song has since been performed several times in Los Angeles. This recording, in particular, was made by Jenny Luna (voice), Marko Danilovski (kaval), Ian Price (darbuka), and me (oud) in Los Angeles in honor of Selim Hubeş:

This last song demonstrates the fact that what was considered Jewish for Middle Eastern Sephardim before the twenty-first century was also shared with gentile (and sometimes Ashkenazi) neighbors. Many of these beloved melodies of the last half of the twentieth century refer to the hybrid culture of the Ottoman heritage. The Sephardic identity that is produced in these songs offers a continuation of a culture that drew freely on multiple linguistic and cultural practices. Jewish life was woven into the Ottoman cultural tapestry in its musical practices. In the memory of Sephardic immigrants, these practices were extended and became the basis for a continued multi-lingual musical environment. Sephardic music in America offered immigrants harmony in their host lands and an accompaniment to the numerous lives that they occupied as they carved homes for themselves along their journeys west.

NOTES

- Referred to as “Judeo-Spanish” by linguists.

- Ibid.

- This was also a phenomenon in Hebrew adaptations of Judeo-Spanish melodies. For more, see: Seroussi, Edwin and Susana Weich-Shahak. 1990-91. “Judeo-Spanish Contrafacts and Musical Adaptations, The Oral Tradition” Orbis Musicae 10. 164-194.

- Benardete, M. J. 1958. Sephardic Folk Songs. Folkways Records FW 8737. LP Record.

- Ibid.

- The song’s earliest recordings by Isaac Sene have yet to be located, but its lyrics have been documented by his wife, Emily Sene.

- From the notebook of Emily Sene from the Emily Sene Collection at the UCLA Ethnomusicology Archive.

- “Estar hecho un pincel” is an expression in Spanish that means that someone is well-dressed or dressed to kill.

- Translation by Giacomo Valentini and myself.

- From the notebook of Emily Sene from the Emily Sene Collection at the UCLA Ethnomusicology Archive.

- Translation by Giacomo Valentini and myself.

- From the notebook of Emily Sene from the Emily Sene Collection at the UCLA Ethnomusicology Archive.

- Translation by Giacomo Valentini and myself.

- No recorded last name.

- No recorded last name.

- From the notebook of Emily Sene from the Emily Sene Collection at the UCLA Ethnomusicology Archive.

- Translation is my own.

- And just one of five record companies that produced Ladino music in the United States

- Bresler, Joel. 2008-2012. Sephardic Music: A Century of Recordings. “Me-Re 6001.” http://www.sephardicmusic.org/labels/Me-Re/6001.htm

- Translation is my own.

- A famous example of this is Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, in which the nightingale song represents undying love but also mortal danger.

- Translation is my own.