by Jeremiah Lockwood, Research Fellow

Lowell Milken Center for Music of American Jewish Experience

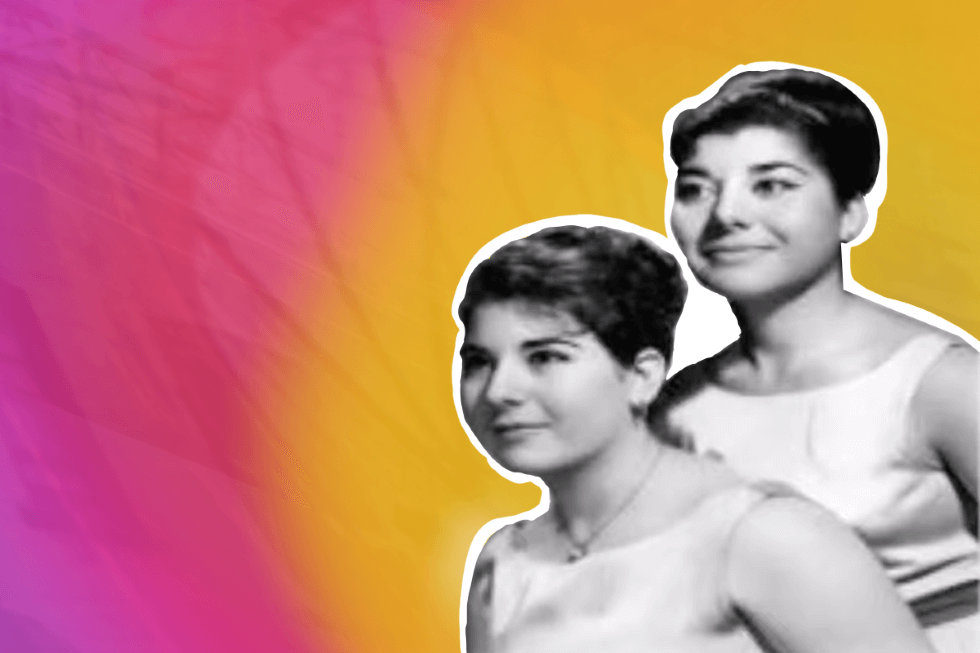

Daughters of a renowned cantor, these remarkable women worked within the parameters of their social world to create a lasting contribution to multiple musical communities.

On January 23, 2022, the cantorial community was shaken by the loss of a leading figure, Robert Kieval, a beloved faculty member of the JTS cantorial training program and elder cantor. I have had the privilege of working with Robert extensively over the last six months, in my capacity as the lead researcher for the Cantors Assembly’s new initiative, the Cantorial and Synagogue Music Archive (CSMA). The CSMA takes as its goal the preservation and dissemination of the privately held music collections of cantors, seeking to salvage vulnerable and unique artifacts of the Jewish sacred music legacy. Robert’s collection of old cantorial manuscripts was legendary among his friends and students and will provide the initial material for the CSMA website, which will launch in the next month. I will have the opportunity to write at length about Robert and pay homage to his work in the coming months but in this post, I will turn my attention to another member of the family.

In these last months, I have had the good fortune to also get to know Robert’s wife, Gayna Sauler Kieval. In the month since Robert’s passing, we’ve had some time to talk and decided to spend an afternoon making an oral history video, along with Gayna’s sister, Bianca Sauler Bergman. In this video, we concentrate on a specific period in their lives, in the years of the 1960s and early 1970s when the sisters were actively pursuing careers as singers before they married and took on roles as wives and mothers.

Gayna and Bianca are the daughters of Cantor William Sauler (1903-1973) a refugee from Nazi Germany who had a prominent career as a pulpit cantor in New York, serving for 28 years at the Brooklyn Jewish Center. Both sisters were remarkable vocal talents, pursued successful careers as singers, and played a role in a musical economy that embraced both the Jewish community and the larger world of art music. The sisters are figures in the transitional period of change from the European Jewish immigrant milieu to the post-World War Two American Jewish cultural landscape. Their lives and music tell an important story about the role of cantorial families as the talent pool for a variety of music scenes. For the Sauler sisters, working in Jewish music went hand in hand with studying and performing European classical music. The culture of their home, focused on vocal music, Jewish liturgy and European high culture transplanted to a working-middle class Brooklyn neighborhood, created the right synthesis to nurture their intense work ethic and an ability to code-switch between Jewish music and elite art music contexts.

Cantor William Sauler had been a successful cantor in Berlin, before emigrating in 1938, under duress, shortly before Kristallnacht and the complete deterioration of German Jewish life. Sauler met Edythe Margolis, who while not a musician herself, was a fixture at the Café Royal, a hangout of 2nd Avenue Yiddish theater and cantorial stars. At one point she dated theater composer Abe Ellstein, although her daughters hastened to note the connection led nowhere. Edythe and William married in 1944. When their daughters were born, William was already the cantor of the Brooklyn Jewish Center, the first of the “Center” synagogues in New York City that contained athletic facilities, a pool and social halls. The Jewish Centers were intended to function as hubs of “Jewish civilization,” a broadly construed social and cultural community as conceived by the influential Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan.

The daughters praised their father’s elegant davening style. A few fragmentary bootleg recordings attest to Sauler’s powerful voice and persuasive cantorial style. Despite his well-honed talent, Sauler’s position was contingent on the support of the community. Throughout his career, he received letters of complaint that would be familiar to any cantor today. The key issues taken were the service being too long, the melodies being unfamiliar or the keys the music sung in being too high for the community to sing along. As Gayna noted, “Robert [Kieval, her husband] got the same letters.” At the same time, Sauler had many boosters and was celebrated by the community. As his experiences attest, the work of cantors is liable to be alternately loved and denigrated depending on interpersonal dynamics within their community.

Sauler’s choir directors included key figures in Jewish music: Leo Low (1878-1960), Oscar Julius (1903-1986), Sholom Secunda (1894-1974) and Jacob Goldstein (?). Secunda was the director when the sisters were growing up and he later became an important part of their musical lives. The cantorial choir was all-male, in accordance with local conservative attitudes about female voices in Jewish ritual contexts (see my blog post about the Malavsky Family Choir performance at the Brooklyn Jewish Center in 1949), however, the sisters provided their vocal talents as ringers in the community choir that sang on special Friday night services when women were included in the performance of the service. They also sang in the numerous synagogue concerts their father produced. The sisters later worked as soloists with Sholom Secunda’s orchestra at the Concord Hotel in the Catskills. Secunda’s “Zol Noch Zein Shabbos” became a staple of their repertoire.

For Gayna and Bianca, music was an intrinsic part of their role in the family. Almost as soon as they could speak, they began to sing. Their father took their talent as a given. Perhaps somewhat playfully, Bianca said, “Believe me, we didn’t want to sing, but he needed us.” She went on to comment, “It never dawned on him that other people opened their mouths and ugly came out. He assumed, you know. We opened our mouths at two years old and lovely came out.” The sisters honed their abilities at local music schools, Bianca at Brooklyn College and Gayna at Juilliard.

After finishing her BA, Bianca took an additional year of study at Juilliard in Opera performance. Upon completing this program, she began an affiliation with the City Opera in 1970, singing roles in Dido and Aeneas and The Marriage of Figaro, among numerous other productions. Gayna too stepped into a promising career path, winning first prize in the first New Jersey State Opera competition and performing roles in Fidelio and Aida.

Throughout the years of their education and early career, the sisters were active as performers on WEVD, the Yiddish radio station that “speaks your language.” The sisters appeared as part of a quartet on a regularly running show on Sunday mornings in the 1960s as part of the Forward Hour. The sisters held rehearsals every Wednesday, presided over by actor Zvee Scooler, who went by the name “the Grammeister” as the announcer, and William Gunther Sprecher (1924-2016), the music director at WEVD. [1] On their Yiddish show they sang mostly Yiddish theater songs by composers such as Joseph Rumshinsky (1881-1956), Abe Ellstein (1907-1963) and Sholom Secunda, the “golden oldies” of Jewish American popular music.

The sisters would rehearse every Wednesday, receiving new music to sing with the house band, and would then arrive early on Sunday to go over the material before performing live on air. Frequently they would serve as the backup singers for guest-star cantors, further cementing their connection to the social world of their father. Their work brought Bianca to the attention of Lazare Weiner. She sang as the soloist on his 1967 album, “Lazare Weiner Songs,” which served as her introduction to the genre of Yiddish art songs.

The Forward Hour radio program imposed a rigorous performance schedule that they just managed to fit into an already bustling life in music. Throughout this period of the sister’s most intense activity in the late 1960s and early 70s, both sisters still lived at home with their parents in Crown Heights.

Their work as musicians was both a compelling aesthetic commitment and a needed source of income. As Gayna said, “It became an occupation, and it became a love.” Their work as professional musicians, although executed on a high level of skill, and not without real rewards in terms of recognition, was never paid well enough to make them economically self-sufficient. Their family, while occupying an elite status as a household of prestigious artists within the Jewish community, were nevertheless limited in their economic means. Bianca was direct about the economic necessity of her work and her willingness to take on all manners of music jobs to stay working and bring in income. Pursuing music jobs was necessary, “If you weren’t gonna work 9-5. I used to do Bar Mitzvahs, weddings. You know—money!” Both sisters maintained multiple sidelines in the Jewish community, in addition to their careers as art singers.

These two brilliantly talented women were able to contribute to the Jewish bi-cultural musical scene, moving between the synagogue and the opera in a manner that was sometimes castigated in male performers. Unlike cantors such as their father’s peer, Richard Tucker, who was pushed out of his pulpit cantorial position as a result of his opera career, the Sauler sisters were able to move between Jewish contexts and opera. But unlike their male peers, no mechanism was in place to ensure that they could make a living.

The Jewish community of the period provided no option for a woman to become a pulpit cantor. The Sauler sisters subscribe to this same ideology that cantorial music is a male idiom, as represented by their father and Gayna’s husband. They reject the idea of women singing cantorial music but make an exception for Perele Feig, a wonderful woman performer of khazones and friend of their family. The sisters noted that Feig was not a cantor and never led synagogue services. They both seemed to consider Feig to be an extreme anomaly, both in terms of her remarkable sensitivity as a cantorial singer, and also in her physical presence. Feig was an unusually large woman with a deep voice. As Gayna commented, “It looked like her husband could fit in her hand.” The Sauler sisters seemed to see Feig as outside of the norms of gender comportment that they themselves fit more neatly.

While their work lives were marked by economic precariousness, ultimately it was their marriages, and not the vagaries of the music business, that set the boundaries on their professional careers. For Bianca, the choice between married life and opera was an unambiguous binary. After three seasons with the City Opera, including a three-week out-of-town residency each Summer season, it was clear to her that a path as an up-and-coming opera singer was not compatible with the responsibilities of being a wife, as she understood it. She effectively ended her singing career in 1973 after getting married and starting a family. For Gayna, her approach to her career path was somewhat more nuanced. She continued to concertize and sing some opera roles in the first years of her marriage and even after becoming a mother. Seeking more economic stability, she began a second career as a pre-school teacher, but continued to work in music as the choir director for her husband, Cantor Robert Kieval, for 18 years out of his 25 year position at B’nai Israel Congregation in Rockville, Maryland, a major pulpit in the Washington D.C. suburbs.

The Sauler sisters’ striving and ambition show something about the labor of Jewish women in the expressive culture workplace, a setting in which labor as artists is both a passion and an economic imperative. Like emotional labor, a term coined to describe the undervalued work of women in domestic settings, [2] the labor of expressive culture is needed to sustain the identity and emotional life of communities but is consistently undervalued, especially when performed by women and minorities.

For Gayna and Bianca, to work as musicians was a seemingly natural choice. Their childhood home was filled with singers and performers and they were expected to help in the family business as performers from a young age. Although this path brought them some remarkable successes and personal satisfaction, from a labor perspective, their careers were structured in a way that provided inconsistent employment and was inadequately remunerated. They faced structural impediments to job security, such as the all-male cantorate and the low wages offered to early career female opera singers. These elements of scarcity were written into their professional destiny, acting as an indelible counterbalance to their impulse to perform, inspired by their life experiences and talents. Despite the impediments to success they encountered, these remarkable women worked within the parameters of their social world to make a lasting contribution to multiple musical communities. Their stories testify to the richness of Jewish musical lives in the mid-20th century and to the complex paths that cantorial lineages have taken, influencing multiple facets of American music.

NOTES

[1] Thanks to Gayna Sauler for offering me additional information on Scooler and Sprecher after an initial mistake in the first draft of this article.

[2] See Arlie Hochschild, The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983).