by Daniela Smolov Levy

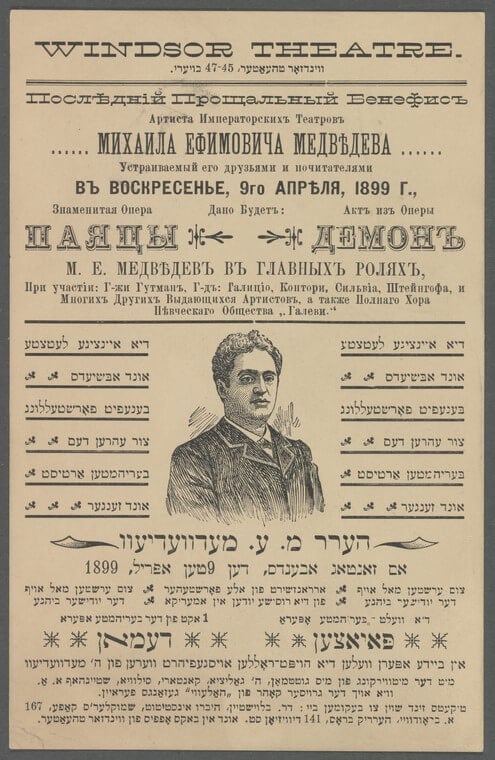

In Russian, the name Mikhail Medvedieff literally means “Bear of Bear”: Misha, the shortened form of Mikhail, means “little bear,” and Medvedieff comes from the word “bear,” medved’. The opera singer Mikhail Efimovich Medvedieff (1858-1925) was thus a Russian bear in the literal meaning of his name, as well as metaphorically, in being a symbol of late nineteenth-century Russian operatic culture.

Except Medvedieff’s real name was Meyer Haimovich Bernshtein. [1] Like many Jews with career aspirations outside the Jewish sphere, Bernshtein adopted a decidedly non-Jewish name to facilitate his professional advancement. And advance he did, from becoming Anton Rubinstein’s protégé at the Moscow Conservatory to securing the prestigious position of Imperial Russian opera singer. From his performances in the premieres of Eugene Onegin and Queen of Spades he also gained the admiration and lifelong friendship of Tchaikovsky himself.

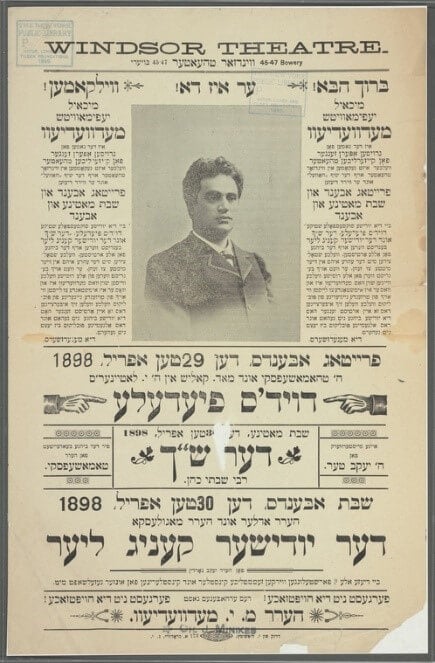

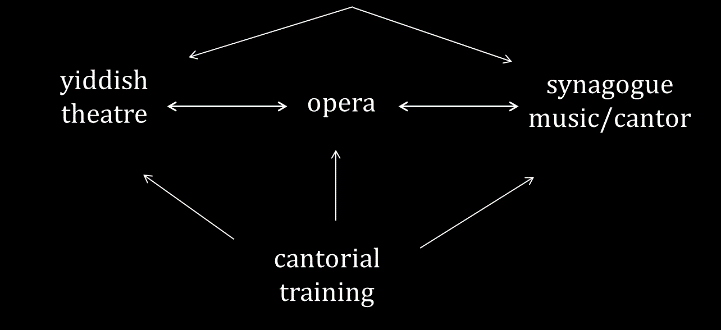

Yet when Medvedieff came to New York in 1898, it was not through typical operatic channels. He arrived by way of the Yiddish theatre, starring in both Yiddish productions and European operas. [2] Medvedieff performed predominantly for the Yiddish-speaking Jewish public, appealing especially to Russians, many of whom knew of him when they were still in Russia. Medvedieff is therefore emblematic of several common forms of cultural crossover in the musical-dramatic sphere of the period: the transatlantic exchange of artists, as a European musician touring America; linguistic crossover, as a singer who performed in multiple languages; and theatre crossover, as an artist who appeared in both opera and more popular musical-theatrical genres. This last form of crossover, Medvedieff’s foray into Yiddish theatre circles, is particularly interesting because it reveals the multifaceted intertwined nature of opera and the Yiddish theatre around the turn of the twentieth century.

The Yiddish theatre was in fact shot through with operatic elements. Historical and contemporary observers have noted – in both positive and negative ways – opera’s presence within the diverse mix of musical styles of the Yiddish theatre. This and other types of overlap between the worlds of Yiddish theatre and opera, however, have yet to be examined in detail, perhaps because the blend was so tight as not to be considered worthy of much attention. (Yiddish operettas, for example, were often referred to simply as “operas.”)

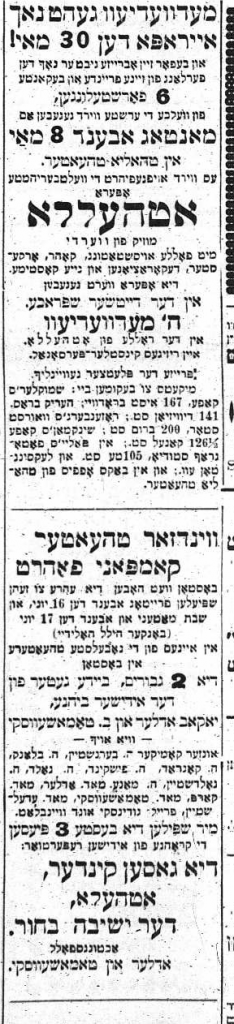

One point of overlap was in shared performers. Medvedieff was just one of a number of musicians, including Melanie Guttman-Rice, Regina Prager, Bertha Kalish, and, somewhat later, Joseph Winogradoff, who appeared in both opera and the Yiddish theatre. Although opera singers in the Yiddish theatre were the exception rather than the rule, their appearance in both environments underscores the interconnectedness of the two spheres. Medvedieff was also among a growing group of artists whom managers like Boris Thomashefsky, Jacob P. Adler, and Moyshe Hurwitz were bringing to America from Europe, introducing new blood and excitement into the highly competitive Yiddish theatre to attract audiences. In 1904, Hurwitz brought over an entire company of opera singers to stage popular French and Italian operas in Yiddish translation at the Windsor Theatre.

Medvedieff performed in an astonishing array of works in the Yiddish theatre context during his American visits between 1898 and 1900. He starred in many shund (“trash”) operettas, including new ones by Hurwitz, in addition to a play by Gordin. He performed standard French and Italian operas like Carmen and Pagliacci as well as portions of Russian operas. He sang in the Polish opera Halka and Halévy’s La Juive (Zhidovka). In the fall of 1899, he even held the official title of music director and composer of the Windsor Theatre. He also gave concerts of Russian opera arias and romances as well as folk songs.

Medvedieff is also representative of similarities in performance style between the Yiddish theatre and opera that stemmed in part from the cantorial training many Jewish boys received as meshoyrerim (synagogue choristers). Medvedieff began singing in the synagogue (his father was a cantor and rabbi), as had Winogradoff, and both subsequently moved to operatic training. In the Yiddish theatre world, Thomashefsky and Kalman Juvelier, along with the prolific composer/librettist duo of Arnold Perlmutter and Herman Wohl, were among many actors and musicians who got their start with cantors before moving to the Yiddish stage.

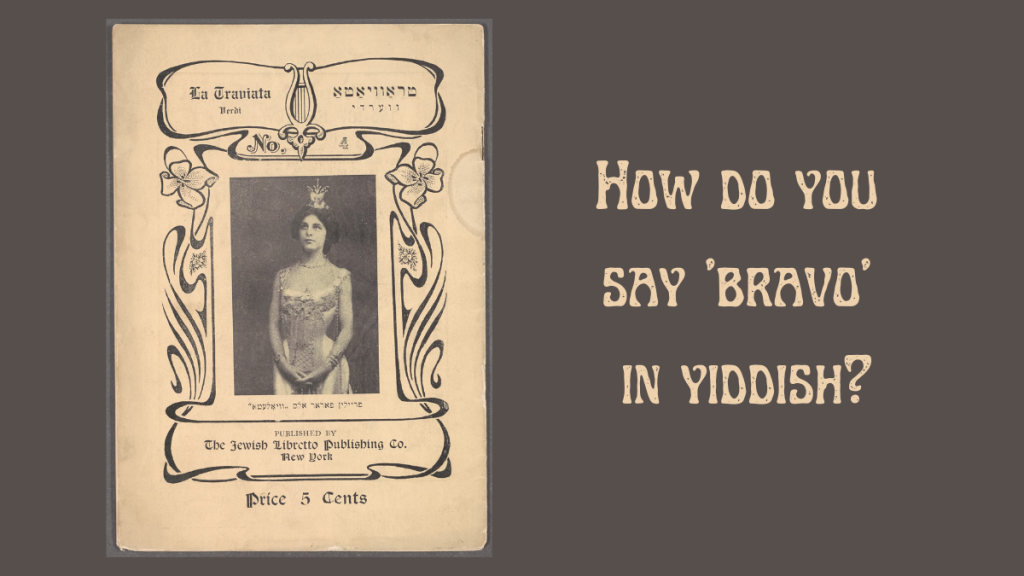

Still another form of overlap between Yiddish theatre and opera was in shared musical and dramatic content. Intellectuals in Yiddish-language circles derided shund operettas for importing chunks of music, large and small, from European operas. [3] Hurwitz’s Ben Hador, for example, features quotations from Il Trovatore and La Traviata in addition to drawing on the Italian operatic style more generally, as had the “father” of Yiddish theatre, Avrom Goldfaden. In subject matter, too, operas and Yiddish operettas often overlapped because both drew on the same literary sources. For instance, while Medvedieff was singing in Verdi’s Otello (in German) at the Thalia Theatre, Adler and Thomashefsky were offering a Yiddish version of Shakespeare’s play. Other subjects common to opera and Yiddish theatre productions included Hamlet, Salome, the Huguenots, Faust, and the Lady of the Camelias.

Although Medvedieff was well past his vocal prime by the time he came to America (despite being only forty), he remains an illustrative case study of how opera was embedded within Yiddish theatre culture. At the end of an illustrious career as one of the best opera singers in Russia, Medvedieff thus returned to his Jewish roots and a Yiddish-speaking environment, harking back to a time when he had been merely, as his childhood friend Sholem Aleichem remembered him, Meyerl from Medvedevka. [4]

[1] Medvedieff took his name from the Ukrainian town of Medvedevka, one of the places he had lived with his family.

[2] Besides New York, Medvedieff performed in Newark, Boston, Brooklyn, Philadelphia, New Haven, Chicago, Baltimore, and Montreal.

[3] See, for example, Rumshinsky’s view in A. Frumkin, “Di fier periodn fun der yidisher operete,” Jewish Morning Journal, April 13, 1928.

[4] Sholem Aleichem, Funem yarid, 1916 (Moscow, Publishing house Emes, 1934).Note: This post is the third in a five-part series based on the five lectures I am giving at UCLA (via Zoom) between January and May 2022, “How Do You Say ‘Bravo’ in Yiddish?: Italian Opera for the Yiddish-Speaking Masses in Early 20th-Century America.” Sign up for the lectures.