by Jeremiah Lockwood, Research Fellow

Lowell Milken Center for Music of American Jewish Experience

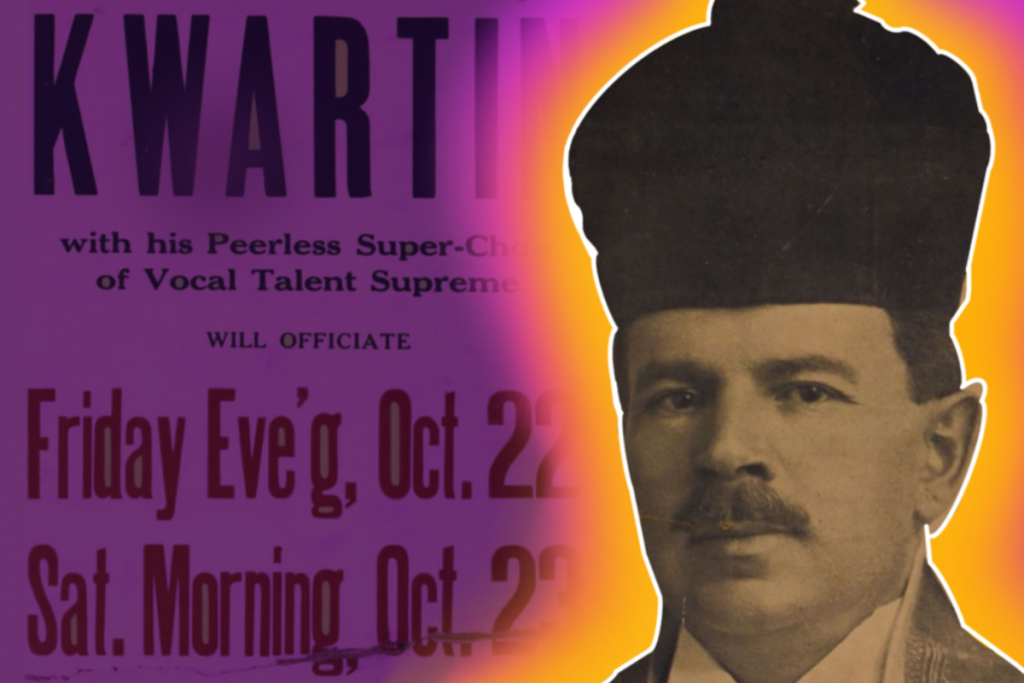

Zawel Kwartin portrays the musical life of his childhood hometown as having offered a paradigm of Jewish art that shaped his music and later career.

In the previous chapters of Mayn Lebn, Zawel Kwartin (1874-1952) tells stories about the relationship of Jews to non-Jews as sources of musical ideas and as patrons of Jewish music in his hometown of Khonorod in Ukraine, when he was a child. In chapter 7, Kwartin focuses his attention on the culturally intimate Jewish space of the synagogue. He discusses the styles of the four main amateur prayer leaders who regularly conducted services on the Sabbath in Khonorod. He also writes about his father who was an important musical influence through his performance of the home ritual of the Sabbath which included intensive singing of the zemiros table song repertoire in Kwartin’s family. In his signature style, Kwartin pokes fun at the overwrought emotions that went into negotiations about who would lead services. Similarly, control over the musical life of the family in his father’s home was also a point of conflict, and his father’s drinking and controlling behavior are noted with winking irony.

Despite the emotional conflicts around music in a small town with limited opportunities for aesthetic outlet, Kwartin describes a committed musical environment in which debates about religious music were a form of local contentious practice and debate, and a variety of styles of musical performance were deeply engaged with by singers and listeners alike. Kwartin’s unabashedly romanticized descriptions of listening to great prayer leaders are a tribute to the obscure small-town Jewish singers he grew up listening to and an aspirational description of an idealized form of communication between cantors and their congregations that Kwartin locates in the folkloric past. He invites his readers to enjoy the image of soulful small-town Jews and presents their unpretentious but deeply moving art as a paradigm for his own cantorial style. While he extols the aesthetic and spiritual qualities of his childhood home, he also makes room for humorous complaints about being hungry, bored and tired as a child during the rigorous amount of time devoted to prayer.

Mayn Lebn

By Zawel Kwartin

Chapter 7

I hear my first prayer leaders in my town

Seventy years ago [i.e. approximately 1880], in a small Jewish town, the Sabbath already had gotten underway at midday on Friday. Jews ran to the public baths where they would get thoroughly sweated-up in the 90-degree heat, sitting on the highest bench. I had a grandfather, Reb Tuvye Soybel, who felt that the bathhouse was not kosher enough for him. In the winter, in the greatest cold, he would go off to the frozen-over river, dig a hole through the ice and immerse himself three time in honor of the holy Sabbath.

They also took us kids to the bathhouse. The heat and the hot steam that burned through your limbs was impossible to stand; yet, as you can see, people did survive it. Coming home from the sauna, I would review the weekly parsha [Hebrew, Torah portion for the week], reading twice through in the Hebrew and then once in the Aramaic translation. Then one had to recite the Song of Songs, with its appropriate melody, of course. Then, I would say the Psalm Hodu l’hashem ki tov [Hebrew, Give thanks to God, for He is good, the first line of Psalm 136] and after that a Ribono shel olam [Hebrew, Master of the infinite; a poetic formula that begins numerous prayer texts]. When my sweet mother saw that I was well worn out from the steam bath and the chanting, and my heart was thoroughly clenched with feeling, she gave me a small plate of chickpeas, so that, God forbid, I shouldn’t overeat before the Sabbath feast.

In the afternoon, my mother would give me a platter with a big piece of fish and various pickled cucumbers and a few pieces of pickled watermelon [1] for me to deliver to Zisel the teacher’s wife, the wife of my rebbe [Yiddish, religious elementary school teacher], Khayim the Blind, so that they too should enjoy the pleasures of the Sabbath.

All cleaned up and hair washed, we went to shul for Kabbalos Shabbos [Hebrew, welcoming the Sabbath; the first prayer service of the Sabbath, held on Friday evening]. Our town was too small to employ a full-time cantor. So, there were a lot of young people who “cantored,” using their voices in a small-town style to lead prayer services. I remember four of these prayer leaders from my earliest childhood, and as strange as it may sound, the earliest singers I heard as a child made the deepest and most powerful impression on my entire musical career. They are deeply engrained in my style and one can truly say that their heartfelt Jewish prayer prepared me for a lifetime on world-class stages and great synagogue pulpits where I was destined to perform in later years.

These were the four prayer leaders: Benye, the son of Yitskhok Mordekhai the shoykhet [Yiddish, kosher butcher]; Aaron Hodes; his brother-in-law Khayim Hersh Hodes; and the last—my uncle Eliezer. Benye the shoykhet’s son, who had learned to be a slaughter from his father, was a fine young man, but no voice had been bestowed upon him whatsoever. He had a sort of “sideways voice” that would fade away like the chirping of a locust. However, he was very knowledgeable about nusakh hatefillah [Hebrew, the manner of prayer]. [2]

Aaron Hodes was a wonderfully beautiful young man and he had a lovely voice; his davening was a little “modern.” This was because he would often travel for business to Kiev, Odessa and other cities where he had the opportunity to hear great cantors. But he couldn’t improvise. In prayer leading one should hear a unique tone, something original—this he lacked. His prayer leading was always well received because the Jews loved to hear modern khazones from him that he had “snacked on” in the big cities. [3]

His brother-in-law Khayim Hodes was a Jew whose face looked like he had just emerged from a sauna. When he got going with his singing, he could tear the drums from your ears. But he was a warm prayer leader. Apparently, his lungs were very healthy because he could stand a whole day at the pulpit working his voice and not get tired.

My uncle Eliezer was the most heartfelt prayer leader of them all. He was a lean little Jew with a thin beard, which consisted in total of six hairs. He belonged to the fraternity of the hacking coughers and it was said in town he had only half a lung. However, he had a beautiful lyric tenor voice. At the age of forty his voice still sounded like a boy alto before his voice matured from a child to a man’s.

When he was singing, he would harshly strain his voice, but he was a lovely prayer leader and improviser, an inexhaustible spring of prayer-melody ideas. Not seldom was he original and spiritual in his musical inventions.

This was the source that formed my concept of old, traditional nusakh hatefillah in earliest childhood. These four Jews aroused my childish fantasies and set a path for my life’s journey.

When it was Friday night and time for Kabbalos Shabbos, each of the four dilletante cantors had his own chassidim [Hebrew/Yiddish, pious ones; here used to connote followers of a specific spiritual leader], his fans in the shul who longed to hear their chosen one chant L’chu neranenah [Hebrew, Come let us sing, the first words of Psalm 95; the first prayer text in the Kabbalos Shabbos service]. Often in shul there would be haggling and struggle over who should lead the service. None of the prayer leaders would let on that the controversy was of the slightest interest to them. [4] But in truth, each of them was dying to be dragged by the beard to the pulpit, and that he should not, God forbid, be hoarse and have his Sabbath ruined.

Finally, with the matter settled, the one who had the honor to welcome the Sabbath Queen felt it was his duty to display all of his craft and began a vocal performance which could extend into late in the night. Everyone’s stomach was clenched because all Friday we had scarcely put a thing in our mouths.

Upon arriving home, we could not immediately plunge into the feast my mother had prepared. We began with prayers in the style of various Chassidic rabbis. My father would wander around the five rooms of our house, deep in thought. After a while he stopped and gathered all the children. He placed the boys on one side and the sisters on the other, and outstretching his hand like a kohen [Hebrew, priest], he blessed us: the boys with “May God make you like Ephraim and Menashe,” and the girls with “like Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah.” [5]

Then came the singing of Shalom aleichem [Hebrew, Peace be upon you; a Friday evening hymn]. After that, my father recited a piece from the Zohar with many words that we did not understand. Before Kiddush [Hebrew, sanctification; a blessing said over wine to start the Sabbath meal] and tasting my mother’s fish, we had to be hushed and indulged many times for our childish mischief.

My father was a Chassid of the Kantekaziver Rebbe, Rabbi Aharon Yoel. But when Friday night came around, he would make a toast in the style of a lot of other Rabbis. He would have a glass of liquor before the fish in the custom of his own Rabbi, but in the middle of eating the fish he would drink a glass in the style of the Talne Rebbe, and in the style of the Rakhmistrivke rebbe—after the fish. He did not slight the custom of the Sadigurer Rebbe, who taught that one should drink earlier than the Yoykh and the Husyatiner—before the meat. [6]

After drinking all of these lovely glasses of liquour, his musical fantasy was warmed up. He sang Kol m’kadeish with the old traditional melody, which we, his meshoyrerim [Yiddish, cantorial choir singers] knew how to accompany him on. [7] By the time he got to Menuchah v’simchah, he had ascended to the upper worlds. He began to create musical fantasies and to improvise until we youngsters could no longer follow him. We tried to follow his compositions by ear so that we wouldn’t embarrass him, leaving him singing all by himself.

The same thing happened with Yah ribon and Tsur mishelo akhalnu. My father was a master at finding a brand-new melody for every piece of the zemiros. The heartfelt Jewish melodies of my father’s improvisations on Friday night were the second source from childhood that formed my concept and feeling for Jewish melody, for the Jewish prayer style that stayed with me for the rest of my life.

I must say something further about these Friday nights. It would get to be late at night. All of my mother’s wonderful delicacies would have us a little tired and worn out. It’s no wonder that after all that eating, chanting and singing we would be slipping into a sweet dream. This did not please my father at all, and he would yell at us: “Peasants, what’s wrong with you? Is today Shabbos or not?”

I was the main recipient of my father’s criticism, and not infrequently there could be heard a resounding slap on my cheek. Why me and not my brothers? I’ll tell you. Although I was still little, my voice was beginning to display skill and beauty. My father well recognized this. And when we sat at our beautiful feast, our zemiros resounded broadly across the town. Dozens of people, Jews and Christians, gathered under our window to hear our Sabbath concert. My father took a lot of pride from this. If we started quieting down, he felt we were doing a disservice to our audience under the window…

NOTES:

1. See Sonya Sanford, “Russian-Style Pickled Watermelon is Everything You Need This Summer,” The Nosher. July 3, 2018. [website] Accessed October 10, 2021.

2. The term nusakh hatefillah is used in cantorial discourse to describe the melodies and modal forms for chanting prayer texts that are deemed traditional. What constitutes nusakh is contingent upon the context of specific communities. Attempts at defining nusakh are both an element in guarding the borders of cantorial professional knowledge and musicological controversy. For a discussion of the term nusakh hatefillah and its history, see Jonathan L. Friedmann, “From text to melody: the evolution of the term nusach ha-tefillah,” Journal of Modern Jewish Studies (2021) vol. 20 no. 3, 339-360.

3. Kwartin references a musical divide between rural and urban musical styles in late 19th century Russia. The major metropolitan centers of Jewish life boasted elite synagogues referred to as “choral synagogues” that boasted impressive architecture and employed professional cantors and choirs. The repertoire of choral singers tended to employ the modern cantorial repertoire of Salomon Sulzer, Louis Lewandowski and other central European cantor-composers who had embraced a choral music style influenced by church music and European art music. In the period Kwartin is writing about, a turn towards cantorial music composed by Russian and Polish-born cantors was emerging in a synthetic style that interpolated cantorial recitative elements into the new choral style. As Kwartin notes, the rural-urban divide was far from absolute, in part due to the economic role of Jews as merchants who traveled extensively. See Vladimir Levin, “Reform or Consensus? Choral Synagogues in the Russian Empire,” Arts 9, no. 72 (2020); Phillip V. Bohlman, “The Jewish Village: Music at the Border of Myth and History,” Jewish Music and Modernity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 3-34.

4. In the original, Kwartin expresses the feigned nonchalance of the prayer leaders as “di gantse mayse ligt im nisht in di linke peya.” Literally, “the whole story didn’t stir his left sidelock.”

5. The formula Kwartin describes for blessing the children is a common home ritual performed on Friday nights before the Sabbath feast.

6. The Chassidic “courts,” each with its own Rebbe (here used to mean a Chassidic leader), Kwartin mentions in this paragraph are of varying degrees of fame and significance, with some continuing to exist into the present and others having dissipated or been wiped out during the Holocaust. Kwartin lightly swipes fun at the customs of Chassidic Jews, including his own family, associating rabbinic leaders with excessive eating and drinking, a frequent topic in anti-Chassidic polemic and mockery. See David Biale, David Assaf, Benjamin Brown, Uriel Gellman, Samuel C. Heilman, Murray Jay Rosman, Gad Sagiv, Marcin Wodziński, and Arthur Green, Hasidism: A New History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018).

7. Kol m’kadeish (All who sanctify), Menuchah v’simchah (Rest and pleasure), Yah ribon (God is ruler) and Tsur mishelo akhalnu (Rock who fed us) are pieces in the zemiros liturgy, a set of mystically oriented Hebrew and Aramaic devotional poems written in various periods and geographical locations between the 11th and 17th centuries that are sung at the Sabbath meals. There are countless melodies that have been composed or used as contrafacta for the zemiros texts. Kwartin notes with typical humor that as his family sings through the hymns, Sholom, the father, is growing progressively more and more drunk. See Nosson Scherman, Sabbath songs and Grace after meals: A new translation with a commentary anthologized from Talmudic and Midrashic sources (New York: ArtScroll Mesorah Publications, 1979).