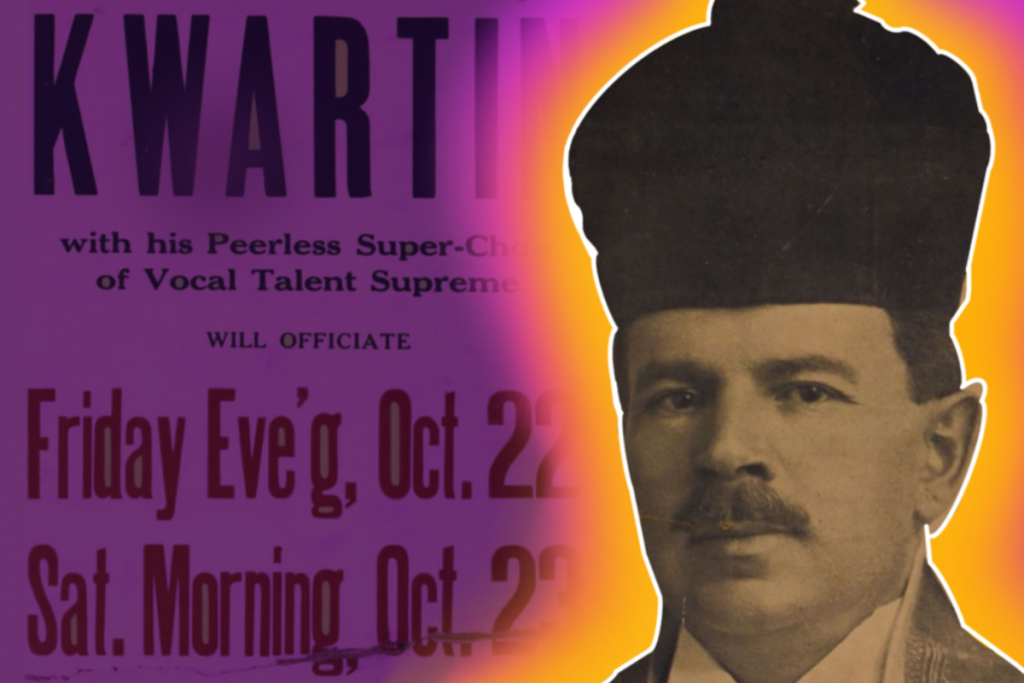

By Jeremiah Lockwood, Research Fellow

Lowell Milken Center for Music of American Jewish Experience

In a fanciful vignette, Kwartin describes how one of the best-known cantors of the 19th century predicted his future greatness.

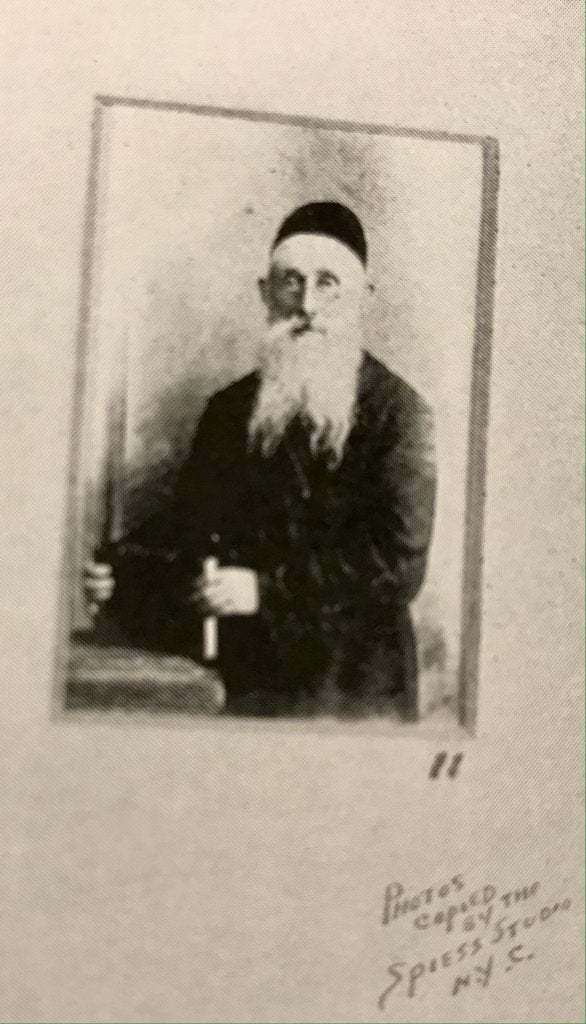

Yeruchom Hakatan (1798-1891) was one of the best-known figures in Russian Jewish music of the 19th century. In the writings of early 20th century cantors and Jewish music critics, Yeruchom figures as an Eastern European foil to Salomon Sulzer (1804-1890), the Viennese cantor most associated with the choral music revolution in synagogue music. Through his musical innovations, Sulzer helped establish the role of the cantor as a musical expert responsible for elevating the community’s aesthetics and presenting a decorous image of the Jews to the non-Jewish world. These social innovations were appreciated by Eastern European cantors and Sulzer’s choral music was broadly imitated. Yeruchom was imagined by later cantors as an upholder of an “indigenous” sound of Jewish prayer music that needed to be protected from the influences of European art music. In his book, Legendary Voices that chronicles the lives of stars of cantorial music, Cantor Samuel Vigoda (1895-1990) describes Yeruchom and his students. Vigoda suggests that Yeruchom was an exemplar of an “east-west” dichotomy in European Jewish music.

And who can tell how far the process of radical transformation of the old but still untarnished typical Jewish motifs would have gone, if not for the counter-revolutionary activities of the East European stalwart representatives of the “Chazzonut Haregesh,” [Hebrew, feelingful cantorial music] who stood their ground, like bulwarks manning the ramparts, determined to preserve the precious treasure which had been handed down from the past… [1]

Vigoda’s fanciful description of 19th century Russian cantors as a militant vanguard against musical assimilation is representative of the discursive use Yeruchom and other “legendary” voices of the Jewish past were put to by later cantors. Yeruchom is cited by Kwartin, Vigoda and other cantors writing in the 20th century to signpost their connection to a pre-modern style of cantorial music. For Kwartin, invoking Yeruchom’s musical lineage supports his self-presentation as a preservationist force in Jewish music.

At the time of the meeting described in this chapter, when Kwartin was 8 years old in 1882, Yeruchom would have been approximately 82 years old and approaching the end of a long and prosperous career.

Mayn Lebn

By Zawel Kwartin

Chapter 9

The words that Getzel the Cantor from Balta had bandied about, that I, a little kid, would grow up to be something no one could predict, and that all of Russia would someday ring with my name—these words were not without some impact on my father. Perhaps some of this had penetrated his mind.

It was on a Sunday which in Khonorod is the day of the big fair. It was shortly after the harvest, when the peasants had already reaped the wheat from the fields. That year was an unexpected success, and the peasants had a lot of money from selling their crops. They filled the shops of the town, buying various merchandise for the winter.

The shop keepers profited piles of money. There was an abundance of wealth from the fair. Late in the evening, after supper, they were counting the profit from the day. We little ones helped counting pennies. My older brother counted the silver coins. And my father himself counted up and set aside the paper bills. I remember until today that the total was 394 rubles—the greatest one-day profit in the existence of our shop.

As you can imagine, everyone was in high spirits. “Oh Shalom,” my mother began, “thank God for all of this. With the profits from the last two weeks, we can stock up on a lot of items for the store. I don’t think you can get everything we need in Uman. It would be good for you to go to Berditchev to get all of the merchandise we need.”

My father agreed, and it was decided that the next week he would travel to Berditchev. The next day, on Monday, before I went to school, my father called me and said, “If you will be a good boy and give your energy to learning, then next week, God willing, I will take you with me to Berditchev.”

A stream of joy flowed through my young body, but I gave no outward sign of my excitement about visiting the great Jewish city. I gave my father a fiery promise that I would eagerly pursue my studies.

The following Monday, we travelled by covered wagon, first to Uman and then to Berdichev; I was excited to be going to that city roiling with Jewish life. So many Jews were chasing and hurrying who knows where; no one told me where they were all rushing off to. The roadways crowded with half dead horses which could barely pull the wagons overbrimming with Jews and Jewesses made a disturbing impression on me. These same streets were later described artfully by our unforgettable author Shalom Aleichem. [2]

My father brought me to all the wholesale shops where he made his purchases. All of this was new for me and full of magic. But the greatest excitement for me was when all of the business meetings were done and my father said to me, “Well, my son, now we will go visit the famous cantor Yeruchom Hakatan, so that he can assess your voice.”

As small as I was, I already knew that this Yeruchom was the highest embodiment of Jewish song and prayer. I do not believe I have presented myself for a greater or more beautiful audience since. Hearing that I would perform my singing for this man filled me with joy and terror mixed together. I was very excited to hear what the greatest cantor, in my eyes, would have to say about my voice; on the other hand, I was terrified that I would not please him and that he would say I was useless and would be better off going back to kheyder (Yiddish, religous elementary school).

When we got to Yeruchom’s house it was about noon. Yeruchom was still standing in tallis and tefillin and was just finishing his prayers. After greeting us he asked my father where we were from and why we had come. My father told the story, that Getzle the Cantor from Balta and his choir had come to our town and listened to the alto voice of his boy and had liked it very much; so much so that he had offered to take me as a meshoyrer [Yiddish, cantorial choir singer] in his choir. He had given no answer to Getzel; instead he decided to bring the child to Beridchev, to him, Reb Yeruchom, so that he would listen to my voice and offer his opinion as to what we should do.

Yeruchom Hakatan gave me a good looking over from behind his spectacles and said to me, “So, boy, sing the piece for me you like best.” I sang my two best numbers “V’hagen B’hadnu” and “Tsur Yisroel.” Yeruchom was slight of stature, but at that moment he seemed to extend high above. He lay his pair of big, stony eyes upon me. [3]

Then he offered his opinion to my father. “The Balta cantor wasn’t lying. The boy has a silky alto voice with an exceptional sweetness.”

Hearing these words, my father’s estimation of me grew, and he said to Reb Yeruchom, “Let him sing one of his own compositions in his own style.” I didn’t have to be asked twice. I started my chanting with fire and ice. I started with “Al Takshu Levavechem,” then “Yishtabakh,” “Vehaofanim,” “Mi Shebeyrach,” and “Yehi Rotson” from the Rosh Chodesh bentshn. [4] I remember how I burned with boyish enthusiasm and strained my voice, giving it all I had.

Meanwhile, Reb Yeruchomn had put away his tallis and tefillin, called for whiskey and cookies, had a toast with my father, and said to him, “Well, what can I say Reb Sholom. I’m already an old man; I’ve heard a lot of talented children in my life, but I have never encountered a child with such a mature understanding of nusakh hatefilah (Hebrew, the manner of prayer, used to describe traditional prayer melodies and the modal basis for cantorial improvisation) at such a young age. [5] In my opinion, he possesses something rare among cantors. He is rich in style; his improvisations are exceptional. And in addition, he has a strong coloratura. Tell me, Reb Sholom, who has he studied with and what cantors has he listened to?”

My father explained that my only “conservatory” up until then were the Sabbath zemiros [Hebrew, hymns] that I sang at the table. My “professors” were the home-style dilletante bal tefilos [Hebrew, prayer leaders] in Khonorod who couldn’t really sing but who knew how to rattle the bones of the town’s Jews with their heartfelt prayer and with their sweet nusakh hatefilah. He also mentioned his brother, my uncle Eliezer, who had a special style of plucking at the hearts of the Jews.

Reb Yeruchom then delivered a few sharp words to my father, that it would be a sin against God and man to neglect the development of such a talent as God had bestowed upon his child. In his opinion, the Balta Cantor’s assessment was correct, and he himself would make the same offer as Getzel. He requested that my father should leave me in his care, as though I was his own child. In addition to teaching me the science of music and singing, he would learn Torah with me, teaching me everything that was appropriate for a religious Jewish child.

I would not have to travel from city to city and from village to village, since Yeruchom didn’t tour anymore. I would have the opportunity to hear him lead services every Shabbos. And when my voice changed and matured, and if my tenor voice was as beautiful as my alto, then, he hoped, my voice would be the best anyone had ever heard, and I could develop into the greatest cantor for the Jews.

Reb Yeruchom stipulated that he would not, God forbid, be remunerated for this; he would have the pleasure of it being said in the future that I was Reb Yeruchom’s pupil.

My father was shaken by what he had heard. But he was not prepared to make a decision about such an important matter without consulting my mother. And so he would go home and let Reb Yeruchom know what the family decided.

But this was nothing more than a facile excuse. My parents had suffered far too much on account of us children for them to decide to send me off into the unknown, at God’s mercy, to eat at strangers’ tables. The question of their child’s future career played a very small role then, the main focus was studying Torah, developing good values and growing up under the guidance of my father.

The only outcome of my trip with my father to Berdichev was that I ended up getting a new teacher…

NOTES

[1] Samuel Vigoda, Legendary Voices: The Fascinating Lives of the Great Cantors (New York, N.Y.: S. Vigoda, 1981), 22-23.

[2] Shalom Aleichem is the pen name of Shalom Rabinovitz (1859-1916), the best known of the classic Yiddish authors. Berdichev was the location of many of his stories. See Dan Miron, “Shalom Aleichem,” YIVO Encyclopedia.

[3] “V’hogen B’adnu” and “Tsur Yisroel” are pieces of liturgy that Kwartin has already mentioned in several points in Mayn Lebn as two of his first performance pieces. See Mayn Lebn Chapter 8.

[4] Al Takshu Levavechem are the first words of the ending section of Psalm 95, chanted on Friday nights as the first piece of the Kabbalos Shabbos prayer service that initiates the Sabbath. Yishtabakh, Vehaofanim, and Mi Shebeyrach are musically marked sections of the liturgy for the Sabbath morning service. The Rosh Chodesh bentshn is the blessing for the new month that is sung by the cantor on the Sabbath preceding the beginning of the month. It is noteworthy that Kwartin later made some of his well-known records on these pieces of liturgy and that his readership would likely know these recordings. [5] The term nusach hatefillah came into popular use by cantors in the mid-20th century in the United States to denote the musical traditions of synagogue prayer melodies, and specifically to refer to the professionalized knowledge of cantors. According to a recent article by Jonathan Friedman, the term was not found in print used by cantors as a musical term before the 1940s. Perhaps anachronistically, Kwartin puts the phrase nusach hatefillah into Yeruchom’s mouth in a scene that is supposed to be taking place in the late nineteenth century, although it is possible the term was used in cantorial jargon before its turn in 20th century written sources. See Jonathan L. Friedmann, “From text to melody: the evolution of the term nusach ha-tefillah,” Journal of Modern Jewish Studies (2021) 20 no. 3, 339-360.