Part Two: The Secret Musical Treasures of Ukraine

By Jeremiah Lockwood, Research Fellow

Lowell Milken Center for Music of American Jewish Experience

In contrast to the prevailing narrative that foregrounds the challenges of live performance in the COVID era, a new online archival research project has garnered success in fostering musical community and new art projects.

In this second part of my report on the Yiddish New York Festival, held this year on December 26-30, 2021, I will focus on the prominent role played by archival research in the klezmer community. For more background about the festival and an appreciation of one of the featured evening concerts, please take a look at last week’s post in Conversations. As I noted last week, concert performances are but one facet of the festival. The majority of its offerings are pedagogical sessions on klezmer music and Yiddish language, and lectures on a variety of topics relating to Ashkenazi culture. In this essay, I will briefly introduce a community-driven archival project that has made a remarkable contribution to our knowledge of Jewish music traditions of the early 20th and late 19th century in the Russian Pale of Settlement.

The life of small-town Russian Jews before the Russian Revolution has taken on an almost mythic significance as a source of imaginative speculation and construction of heritage for Jewish people of European descent, in part through the influence of textualized and mediatized image of the shtetl [Yiddish, small town] constructed in the stories I.B. Singer and the spectacle of the musical Fiddler on the Roof. Yet before its afterimage began to be reconstructed by post-Holocaust artists, Jewish urban intellectuals looked to the Pale of Settlement as a source for knowledge about Jewish folklore. The push to tap the shtetl for the authenticity of its Jewish lifeways was especially important to the field of Jewish music. Ethnography in the Pale was conducted by urban Jews, most famously in the expeditions led by author and folklorist S. Ansky in the years 1912-14. One of the participants in the research project, Abraham Rechtman, wrote a book about the Ansky expeditions was recently published in an English translation.

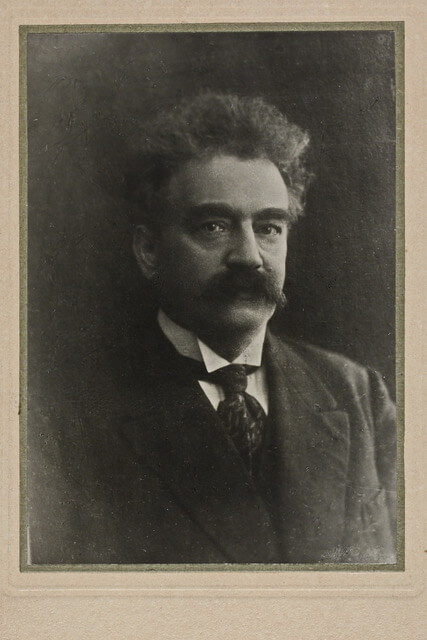

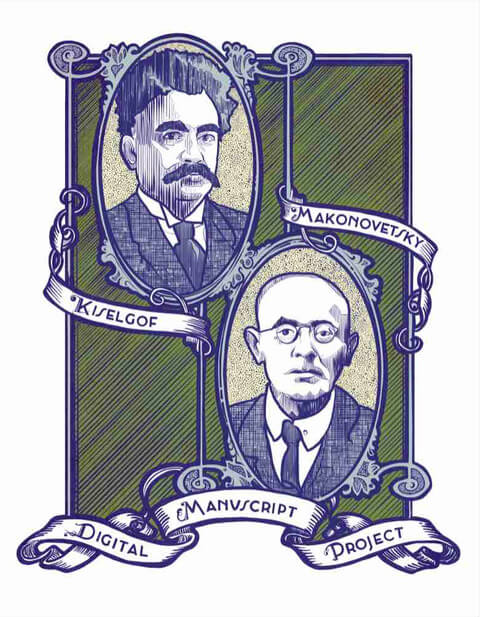

Among the experts who participated in the Ansky expedition was Zinovy Kiselgof (1878-1939), a musician and participant in the influential Society for Jewish Folk Music in St. Petersburg. Kiselgof amassed a collection of cylinder sound recordings and transcriptions of Jewish folk songs, cantorial pieces, Chassidic nigunim (metered devotional melodies, often employing wordless vocalise) and instrumental pieces.

Instrumental wedding dance pieces are of special interest to the international community of klezmer performers. Emerging in the late 1970s, the klezmer revitalization movement is vibrant and popular, but suffers from a lack of primary sources. The Kiselgof material has long been known to be extent, but was held in the Vernadsky Archive in Kiev, Ukraine and was largely inaccessible to scholars. During the Soviet period, American and Western European klezmer researchers had little opportunity to cross the Iron Curtain. Even after the fall of the Soviet Union the local culture of archives in Ukraine mitigated against access to the material. Some researchers who came to the Vernadsky Archive were turned away. If anything, these experiences of being forbidden access increased the romance and mythic allure of these musical treasures.

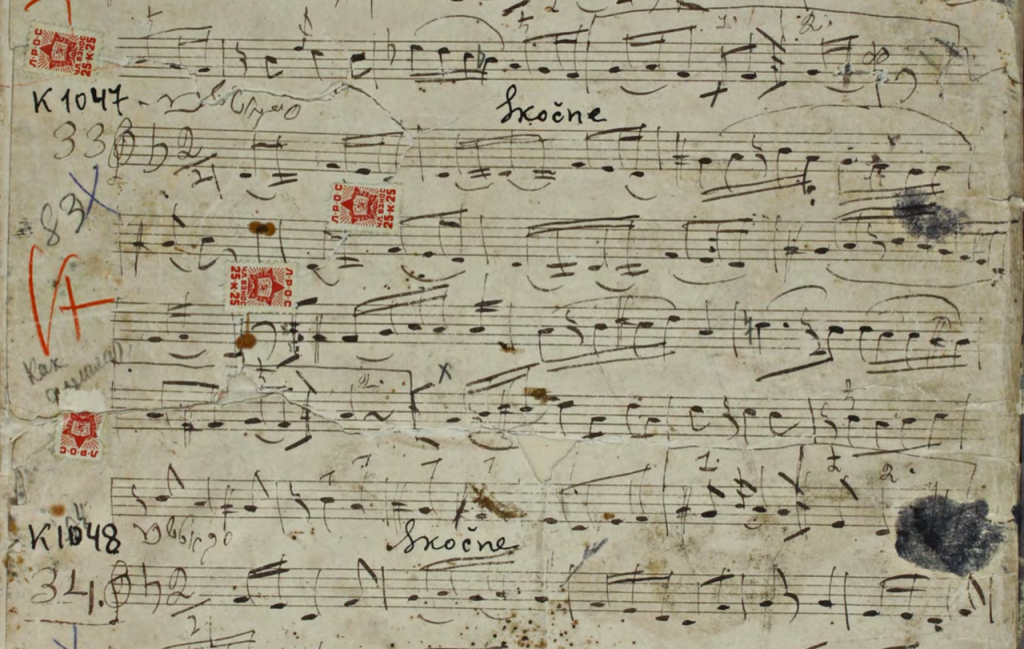

In a surprising and somewhat mysterious turn of events, a Ukrainian academic named Anna Rogers (née Gladkova) was able to succeed in accessing the materials where a generation of previous scholars had failed. A few years ago, while still a PhD student in Tokyo, Rogers brought a letter of inquiry from her friend and fellow klezmer afficionado Mariko Mishiro, a student at Tokyo University of Arts, requesting research access to the Kiselgof materials. Somehow, the imprimatur of the letter from a Japanese university enabled Rogers to convince the archivists at Vernadsky to allow her to take 850 digital images of pages of scores from the Kiselgof collection. This trove of material constitutes 1400 individual pieces of music. Included in the collection is a 230-page manuscript of wedding instrumental pieces that were transcribed by Abraham Yehoshua Makonovetski.

This collection has become the basis for the Kiselgof-Makonovetsky Digital Manuscript Project (KMDMP) a new initiative of the Klezmer Institute, an organization dedicated to supporting “Ashkenazic expressive culture through research, teaching, publishing and programming,” according to its institutional slogan. The KMDMP has taken as its goal fostering radical accessibility of this previously hidden body of song. The scores have been placed in an openly accessible online archive. The Project, helmed by Klezmer musicians/scholars Christina Crowder and Clara Byom, in association with an advisory board that includes luminaries of Jewish studies and musicology, has taken as its primary goal to re-transcribe the antique and in many cases badly damaged scores. These archival images of century-old sheet music are the basis for brand-new digital scores, created using computerized music notation software.

In the year since the image files of the old scores went online, 800 tunes have been transcribed as digital scores. While Crowder emphasizes that the scores are not “performance ready,” and are in need of a critical eye and some editing, they are radically available for musicians who are interested. The transcribers are almost all klezmer performers themselves, drawn from the international community of professional klezmer musicians and skilled amateurs. They are artists who have taught or studied at music camps like KlezKanada, Yiddish Summer Weimar, and Yiddish New York. Crowder estimates that this newly revealed corpus of music has increased the number of pieces of pre-Holocaust klezmer repertoire by five-fold.

This transcription process that has so deeply enriched the klezmer repertoire has been entirely driven by volunteers from the music community. As Crowder told me, “A core value of the project is to flatten the distance between experts and newcomers…The traditional way for research to be presented is, I work and then I present. There’s so much of this material. We’re trying to create a public model. We’re trying to create access. No one wants to wait years. This stuff has to go out all at once. It’s been sitting behind walls for 100 years. Why should we be gate keepers? This is the inheritance of klezmorim [Yiddish, instrumental musicians].”

The methodology of the KMDMP raises as many questions as it answers. It upends traditional methodical approaches to research reportage, and as such flies in the face of established academic protocols. Instead, KMDMP is situated at a fascinating juncture of historical musicology and group art-making practice. The work of transcription seems to hold as its impetus use value for musicians, prioritizing the creative potentials of heritage materials over historical analysis. At the same time, the transcriptions are being conducted with great sensitivity to the source material, with copious notes and analytical remarks offered on many of the transcriptions.

One can imagine how useful this work will be to future projects of historical musicology and musical philology. There is much work to be done untangling the sources for the different pieces. Determining what musical traditions and musical personalities these melodies derive from is still at a germinal point. The heterogenous body of materials being amassed in the transcription repository is both a goad to creativity and the basis for multifaceted research initiatives that may well take a generation or more to conduct.

The transcriptions, on the other hand, are being produced at breakneck speed, spurred by innovative community events described as “digitizathons.” Digitizathons are synchronized research events that take place on Zoom at which volunteers around the world work together to transcribe pieces from the collection. A google search suggests that the term “digitizathon” is a coinage of the Klezmer Institute, putting them at the forefront of new community-based technologically aided research endeavors. These successful events have been significantly supplemented by the work of one tireless transcriber, Hannah Ochner, a German scientist who produces transcriptions on an almost daily basis.

At the Yiddish New York festival, Christina Crowder presided over two events each day; the first, a multi-part lecture series titled “The Secret Musical Treasures of Ukraine,” and the second, a lecture demo titled “Playing Kiselgof.” The lecture series saw Crowder partnered in dialogue with Zev Feldman and other scholars who are participating in the The Kiselgof-Makonovetsky Digital Manuscript Project, discussing the music and issues arising from this trove of ethnographic and historical data. Two of the lecture sessions, conducted with Feldman, were an open process research session, in which Crowder would play through a melody from the archive, and the two scholars would discuss their impressions about the music’s stylistic sources and possible provenance. Her lecture demo sessions also saw Crowder playing through pieces from the newly digitized and transcribed music collection. Crowder told me that since the Kiselgof material has become available, “I only want to play this now. It’s exciting to dig in.”

In the lecture session of “The Secret Musical Treasures” on Tuesday, December 28, Crowder was joined by the liturgy panel of the KMDMP, represented on this occasion by Cantor Sarah Myerson and graduate student in ethnomusicology, Gabriel Zuckerberg. The audience for the session included scholars on Jewish music; the group discussion was given nearly as much time as the presentation. Crowder and her associates focused on the intentionality of how the scores that are being created from the archival sources reveal the fact that editorial decisions are being made. While the digitized scores take as their goal accurate reproduction, the scores raise questions about the representation of sound and language; this issue is especially prominent in liturgical scores in regard to transliterations of Hebrew prayer texts.

The liturgical scores in the Kisselgof collection often feature transliterated texts, but these transliterations raise questions and problems in their interpretation. Myerson and Zuckerberg noted the inconsistencies in styles of transliteration, and in the accents represented. The standard conception of Hebrew phonology in Ashkenaz as divided between a “Litvish” northern European accent, and a Southern European “Polish” accent is drawn into question by the testimony of musical scores that show some cantors in Ukraine, a South Yiddish dialect area, that use what is understood today as a Litvish accent. This fairly technical area of debate was attended to energetically by the audience members, many of whom joined in the conversation in the chat function, offering interesting comments and conjectures about the meaning of the cultural issues raised by the textual evidence of accent transcription.

Watching this lecture session on Zoom, I jumped straight from the multi-participant conversation to a live concert video, transmitted from Berlin. The concert featured the duo of Susi Evans on clarinet and Szilvia Csaranko on accordion. As if to further underscore the transformational potential for the KMDMP on contemporary klezmer practitioners, the concert was entirely composed of pieces the performers had selected from the Kiselgoff collection.

The sprightly and energetic performances from Evans and Csaranko were inspiring and pleasurable, offering a glimpse into how fruitful the KMDMP has been in creating new avenues for creativity. In contrast to the prevailing narrative that foregrounds the challenges of live performance in the COVID era, the KMDMP has garnered success in fostering musical community and new art projects. The Project, its directors and participants have embraced the digitally mediated experience of life under COVID. Their ability to come up a project idea that can succeed in these trying circumstances of isolation point to the special qualities of archival-based research and its affinity with the digital environment.

The internet, perhaps, has a special advantage to offer as a medium of transfer between the past and the present. The computer screen and the access offered by search engines and online archives creates a horizontal, democratizing relationship between archival materials and the researchers and artists who would approach them. Instead of the forbidding remove and institutional gate-keeping endemic to traditional archives, digital spaces foster a kind of intimacy. The materiality of digital platforms moves all of the processes of research—gathering materials, analysis, discussion and debate with peers, research reportage—into the intimate space of the home. By embracing this intimacy as a feature of its research agenda, rather than looking at it as a problem that needs to be fixed, the KMDMP has been markedly successful in recruiting participants and putting them to work in ways that allow all participants to experience the pleasure of achievement as contributors to the group project.

This is a powerful institutional model and has already born successful outcomes. The presence of KMDMP at Yiddish New York was a bright and felicitous counter-narrative to the problems of COVID isolation and contraction of community. Even as we move forward into a post-COVID era (or period of waning and waxing degrees of crisis), it seems likely that the digital community model offered by KMDMP will remain a useful model for group projects.